Greetings,

This week we looked at the crucial decisions of the 2nd Punic War, and how Hannibal won very dramatic battles, but ultimately could not defeat Rome.

Tradition tells us that Hannibal’s father from an early age made his son swear a sacred oath to hate Rome forever and do all he could do bring about its destruction. We saw last week how Rome’s policy toward Carthage after the 1st Punic War was at best foolish, at worst deliberately provocative. With control of the army in Spain and war with Rome declared, Hannibal determined to make the most of his opportunity.

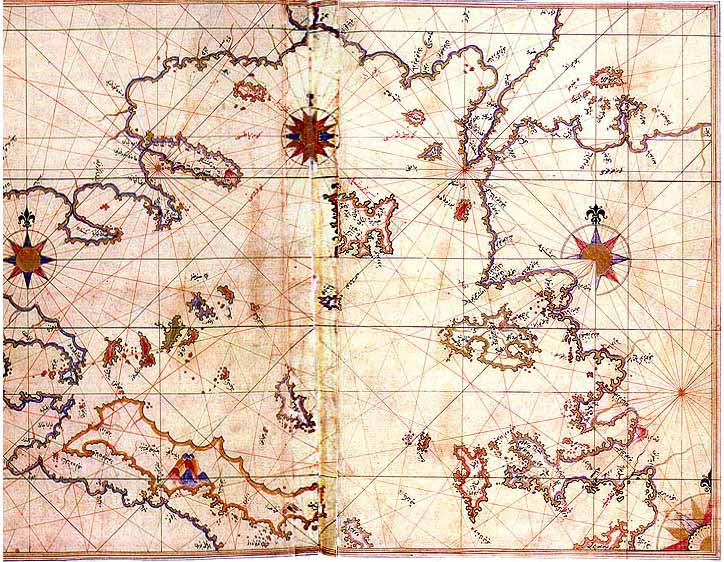

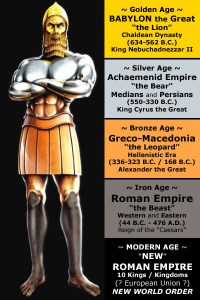

Given that the controversy that started the war involved Spain, I think Rome assumed that the war would be decided in Spain itself. But Hannibal had other plans. He did not want to secure Spain, or even regain control of territory Carthage lost after the 1st Punic War. Hannibal wanted to reverse time, and create the geopolitical situation that existed in the mid-5th century B.C., when Carthage dominated the Mediterranean and Rome was little more than a minor city-state in Italy.

be decided in Spain itself. But Hannibal had other plans. He did not want to secure Spain, or even regain control of territory Carthage lost after the 1st Punic War. Hannibal wanted to reverse time, and create the geopolitical situation that existed in the mid-5th century B.C., when Carthage dominated the Mediterranean and Rome was little more than a minor city-state in Italy.

I don’t care much for the romanticizing of losers that historians often engage in (i.e. Napoleon, R.E. Lee, etc.). But it may be true to say that Hannibal did invent the art of strategy in war. The idea of “strategy” in battle was an entirely foreign concept in the ancient world, much like the idea of strategy in handshake might be foreign to us. We think of a handshake as a handshake. For the ancients, battle was battle. Armies marched into a field and squared off. May the best man win. For the Romans especially, the idea of strategy smacked of dishonor, of cheating.

Perhaps necessity was the mother of invention for Hannibal. Or perhaps the fact that he essentially grew up with his father away from Carthage meant that he had no particular attachment to any cause or code, just victory. The Romans may not have praised Hannibal for the practice of his art, but they did learn from him nonetheless.

Hannibal’s army did not nearly equal Rome’s in size, so he concocted a bold strategy to attempt to achieve his aims. He knew that to “reverse time” he would have to beat Rome in Italy itself. Without control of the sea, however, that meat that Hannibal had to get there by land, which meant crossing the Alps.

Once in Italy, Hannibal hoped that some big military victories would inspire those that Rome had conquered and incorporated into their federation to switch sides. Hannibal believed he had a strategy to provoke Rome into big enough battles that would allow him a chance to impress his potential Italian allies.

Hannibal went back and forth through central Italy, burning towns and farms. Naturally the Romans grew furious and rushed headlong to attack him, and what luck! Hannibal had foolishly placed himself between a lake to his south and some hills to his north, making retreat difficult. The Romans felt they had him dead to rights.

Except Hannibal hid good portions of his best troops behind those hills, and when Rome rushed in, Hannibal sprung the trap, driving thousands of Romans into the lake and splitting Roman lines. He inflicted perhaps 20.000 casualties on Rome.

The Roman dictator Fabius concocted a bold strategy designed to starve Hannibal of both food and battles. Fabius saw that Hannibal needed to win allies to his cause to succeed, and therefore needed to impress others. If he denied him a chance at glory, Fabius reasoned, he would help prevent Roman allies from feeling tempted to flee. If he denied Hannibal food, he would force Hannibal to get food from the very people he claimed to try and liberate, the very people he needed to have as friends.

Fabius’ strategy had many merits, but it proved very difficult to maintain politically. People had to watch the Roman army snipe at Hannibal’s heels while their farms went up in smoke. Additionally, Fabius did not appeal to the Roman sense of glory, the Roman sense of their own greatness. They could not not stomach for long the idea that they simply could not defeat Hannibal head-on. Alas for Rome, Hannibal thrived on this very sense of Roman superiority.

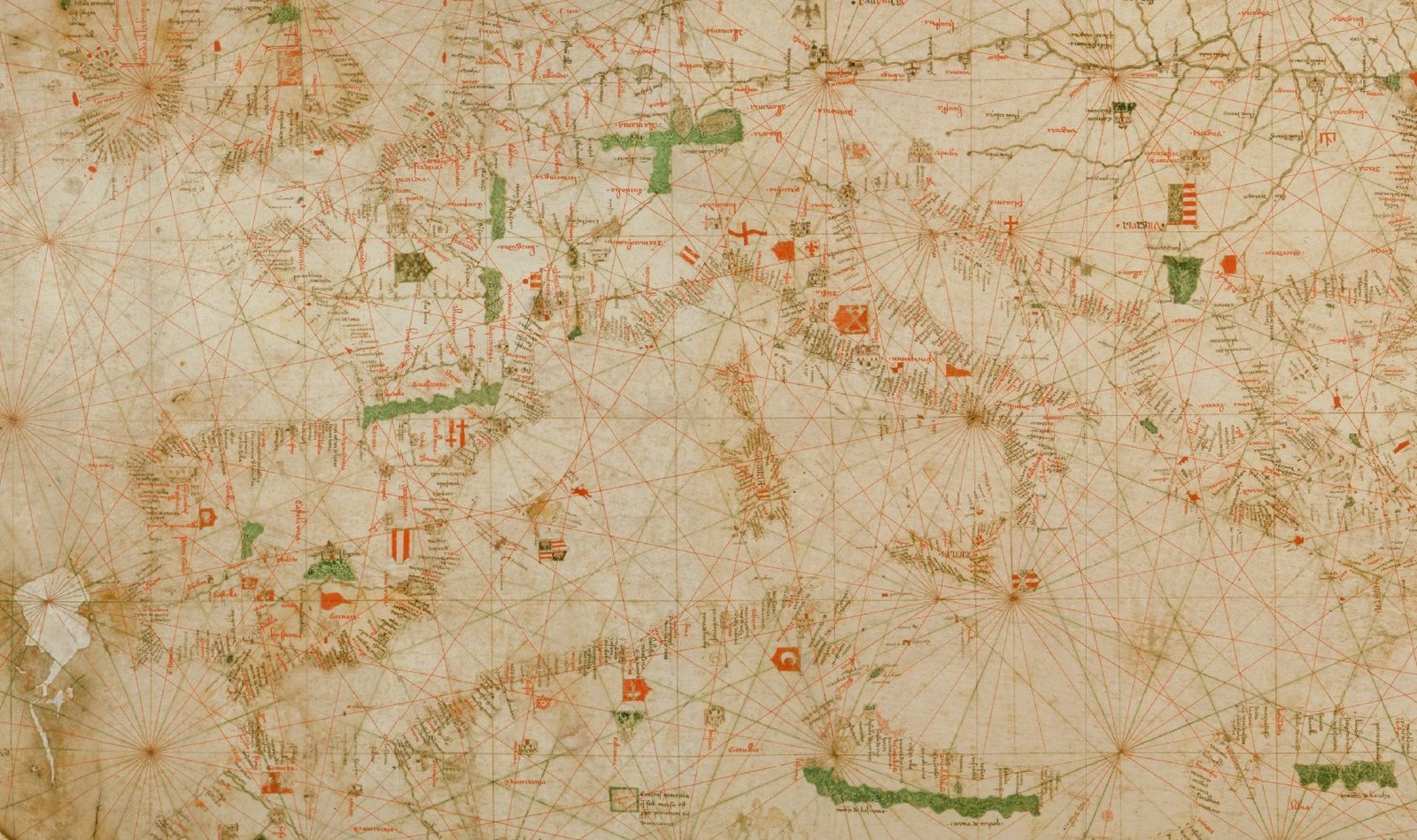

Hannibal then went to south-east Italy, where once again he feigned weakness. He arrayed his army in an open area, which would allow Rome to use its superior numbers. He even camped out in front of a river, which made retreat almost impossible for him. All this looked just too inviting for Rome, who took the bait once again and plunged into the attack in the famous Battle of Cannae. This visual shows the results:

Once enveloped by Hannibal, Rome’s superior numbers meant next to nothing. In what was one of the bloodiest battles of all time, Rome suffered perhaps as many as 70,000 casualties.

In three battles, Hannibal inflicted at least 100,000 casualties, and yet Rome fought on, and eventually won the war. With Scipio Africanus in command, Rome shifted its strategy, fighting in Spain and Africa to eventually force Hannibal to leave Italy. Once in Africa, Scipio needed just one battle at Zama to force Carthage to surrender.

How and why did Hannibal lose? He won the biggest set-piece battles, save the last, but this could not translate into victory. Some point to the fact that Hannibal asked for reinforcements from Carthage, and Carthage refused. Was Hannibal then, let down by his home country, and can we attribute his failure to this?

I am already on record as rarely liking the “doomed/betrayed romantic hero” interpretation of history, and Hannibal is no exception. I think Hannibal failed for reasons of his own making:

- Hannibal chose an all or nothing strategy of his own devising. He chose a strategy that would isolate him from supply lines or the possibility of quick and easy reinforcement. The fact that Carthage denied him extra troops should not, therefore, surprise us. Where would they come from? Rome had already begun to attack overseas and Carthage had every reason for concern regarding their territory in Spain.

- Hannibal needed victories to win allies. To beat Rome with a smaller army, he needed to draw Rome out and make them angry. To make them angry he resorted to devastating local towns and farms. But these were the same people he wanted to “liberate” from Rome. How could he make friends with them by burning down their towns?

- Hannibal did not understand the nature of Rome’s alliance system. One reason for Rome’s success was their general clemency with people they conquered. Those incorporated into Rome owed them only taxes and military service. Hannibal did get a few provinces/towns to leave Rome, but to help encourage them, he had to offer more than Rome did for an alliance. For example, Hannibal got the key port city of Capua to come to his side, but only by exempting them from military service altogether. So even when Hannibal gained allies they did not help him very much.

Few could equal Hannibal on the battlefield, but Hannibal could not make political use of his victories.

It’s a difficult concept to grasp, but I do hope that the students saw that the result on the battlefield is not the only thing that matters in determining who wins wars. One only has to think of the Alamo, Thermopylae, or the Charge of the Light Brigade to see how battlefield defeats can become political victories, and this Rome managed to do. For example, they publicly rewarded Varro, the general who led Rome to disaster at Cannae. He was transformed into a hero of Rome’s resistance to Carthage. Machiavelli, commenting on this seeming peculiarity, wrote in his Discourses,

As regards [Roman attitudes towards] faults committed from ignorance, there is not a more striking example than Varro, whose temerity caused the defeat of the Romans by Hannibal at Cannae, which exposed the republic to the loss of her liberty. Nevertheless . . .they not only did not punish him, but actually rendered him honors; and on his return, the whole order of the Senate went to meet him, and, unable to congratulate him on the result of the battle, they thanked him for having returned to Rome, and for not having despaired of the cause of the republic.

Before sharing this with the students, I asked what they would do with Varro in the Senate’s place. Most of them said that they would have Varro killed, or at least banished. But then I asked them,

- Did Varro break any laws?

- Was Varro derelict in his duty as commander?

- Did Varro own up to his mistake?

- Did he show courage in returning to Rome?

In the end, despite his colossal blunder, Varro trusted in the laws and institutions of Rome, and this attitude, shared by most Romans, would be one of the main keys to Rome’s eventual victory. It is worth noting that after the Carthage’s defeat in the Battle of Ecnomus at sea during the 1st Punic War (256 B.C.) the Carthaginians executed their admiral Hanno in humiliating fashion.

The war contains other lessons, especially if we accept the truth of the traditional story of Hamilcar teaching his son to hate. The strategy Hannibal employed does bear the marks of someone unleashing years of pent of fury. Anger can drive one to do much in a short time, but it also carries you beyond normal limits, beyond proper bounds. Did Hannibal find himself in such a position, even after Cannae? Did he lose energy and drive after this battle because, having exhausted his anger, he had nothing left?

We can make some comparisons to Nazi Germany, where Hitler stoked rage and anger for Germany’s supposed humiliation after W.W. I. In 1939 they unleashed that fury in what became 2 1/2 years of blitzkrieg that gave them almost all of Europe. But when they paused and looked around, they had bitten off more than they could chew, adding the Soviets and Americans to their list of enemies, to say nothing of their already existing enemy England. The defeat they suffered as a result in 1945 was far worse than the one they endured in 1918.

“In your anger, do not sin” (Eph. 4:26).