I have read very few books on the topic of American slavery, but Alan Taylor’s The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832 is the  best book I’ve read on the subject. It has gotten national attention, and deservedly so. Taylor reveals alternate angles and puts a human faces on a great national disaster. He avoids getting preachy, and he doesn’t need to be, for his writing, and the story he tells, does it for him.

best book I’ve read on the subject. It has gotten national attention, and deservedly so. Taylor reveals alternate angles and puts a human faces on a great national disaster. He avoids getting preachy, and he doesn’t need to be, for his writing, and the story he tells, does it for him.

As to why one should focus on Virginia. . . . Well, first, it’s his area of expertise. But Virginia arguably had more influence on the founding of this nation than any other state, and so the focus has justification in any sense. Virginia has more than slavery in its history of course, but slavery had an enormous impact on us as a whole, and so in some ways Virginia’s story is America’s as well.

Two things make this book a great success.

Taylor puts special focus on the lives of struggling plantation owners. Some of them believe, or at least almost believe, in the injustice of slavery. But they also felt trapped. Many had debts from living the required “Virginia Gentlemen” lifestyle that needed paid off. Many farms started failing due to bad weather and failing soil. Many also worried that freeing slaves might create a de facto army of those who would eagerly do them in. In their minds at least (Taylor’s book has copious original source footnotes) they had inherited tiger riding from their fathers and could not get off. Many at least wanted no more slaves in Virginia than they already had, for fear of tipping the ethnic balance against them even more. But again, they trapped themselves by their view of slaves as property. The whole practice of slavery built itself on a certain idea of property, and the liberty of property. Within this framework ownership of slaves could never be restricted. Countless idealistic 20 year olds become weary and defeated 40 year old inheritors of failing estates. The web of of sin ensnared just about everyone, including many who initially wanted nothing to do with it.

Of course this sense of feeling trapped had a way out, but it would involve not just tinkering with the existing social system, but destroying it root and branch. Most simply did not have either the vision or the courage to do this (as an aside — if we judge a man by his contemporaries George Washington shines brightly while Jefferson flows along with the mass. Washington not only freed his slaves but provided land for them and a fund for their medical care. This may have been easier for him because he had no children, but still, he who sought so much to be a Virginia gentlemen for much of his life willingly let that go at the end. Of course this does not excuse everything, but should be noted).

This web involved not only personal contradictions but political ones as well. Virginia state politics routinely pitted county vs. county, so certainly they had no love for the federal government. But when war with the British came many demanded federal troops to protect their plantations and prevent slaves from running away, and many demanded federal restitution for runaway slaves. At least in Taylor’s book, few if any saw the hypocrisy in this, a willful blindness that sin often creates.

Another fascinating plot in the book deals with the impact of the American Revolution on slavery in Virginia. Many founders believed that slavery would die out hopefully on its own within a generation of the American victory. Many perhaps followed Jefferson’s assertion (in his original draft of the Declaration) that slavery had a lot more to do with the British than the Americans, and once they left, the condition of slaves would inevitably improve.

The laws of primogeniture seek to keep estates intact by preventing them from suffering division among multiple heirs. As long as slaves counted as part of an estates’ property, freeing them brought many difficulties under primogeniture law and custom. In abolishing primogeniture laws, many may have thought that their absence would indirectly help slavery disappear. But in increasing social and political freedom, they increased their economic freedom as well. In a cruel twist of unintended consequence, slave owners now found many more ways to profit from their slaves, including selling and even renting them at much greater rates. And this meant, first, that slave families got broken up much more frequently than before. Secondly, it meant that the possibility of some cordiality and respect for slaves by masters (Taylor shows how this did happen on occasion) due to familiarity and stability eroded quickly. In other words slaves became much more like disposable assets rather than valuable family heirlooms. Finally, the extra profits from slavery made a political solution to the problem much more difficult. Too many hands got dirty.

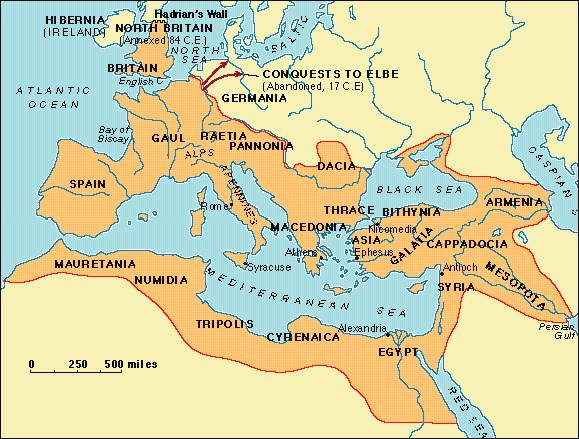

Matters complicated themselves further during the War of 1812, when invading British armies sought to liberate slaves whenever possible. Many slaves “switched sides” and served with British regiments as scouts and guides in what was unfamiliar territory for the British. Who does one root for in these circumstances?

Today we cannot safely distance ourselves from this and claim it has nothing to do with us. Maybe your entire family grew up in Maine. But Virginia’s story is part of all Americans, and the state certainly played an unusually significant rol in the founding of the United States. We have to face this, and should not spare anyone in any era. Marginal Revolution recently posted the following blurb on George Washington (full article can be found here)

During the president’s two terms in office, the Washingtons relocated first to New York and then to Philadelphia. Although slavery had steadily declined in the North, the Washingtons decided that they could not live without it. Once settled in Philadelphia, Washington encountered his first roadblock to slave ownership in the region — Pennsylvania’s Gradual Abolition Act of 1780.

The act began dismantling slavery, eventually releasing people from bondage after their 28th birthdays. Under the law, any slave who entered Pennsylvania with an owner and lived in the state for longer than six months would be set free automatically. This presented a problem for the new president.

Washington developed a canny strategy that would protect his property and allow him to avoid public scrutiny. Every six months, the president’s slaves would travel back to Mount Vernon or would journey with Mrs. Washington outside the boundaries of the state. In essence, the Washingtons reset the clock. The president was secretive when writing to his personal secretary Tobias Lear in 1791: “I request that these Sentiments and this advise may be known to none but yourself & Mrs. Washington.”

Ugh.

Kenneth Clark made the astute observation in his Civilisation series that a society really depends on confidence — confidence in institutions, in laws, in “what we’re about,” and in each other. Without this belief, civilization will collapse quickly, for the foundation upon which our laws, economy, etc. stand will cease to exist. With it, a society can withstand even great disasters (i.e. Rome in the 2nd Punic War). And this raises the problem of how we teach our past. What will happen to us if we can have no “confidence” in the sense Clark meant it?

Someone recently asked me the great question, “Is it the duty of a Christian teacher to promote patriotism, love of country, and devotion to the American way of life?”

To me this question should receive a strong and resounding “No,” in the main, but with a smaller, qualifying, parenthetical “Sort of,” attached to the epilogue of the “No.”

As C.S. Lewis pointed out in Mere Christianity Christians easily fall into the trap of what he called “Christianity and. . . ” We should apply our Christianity to all areas of life certainly, but “Christianity and Pacifism,” or “Christianity and Low Taxes,” easily morphs into “Pacifism and Christianity,” which then leaves you with just “Pacifism.” The Truth stands above all civilizations and must remain so in order that civilizations might learn, repent, and change. Whenever the Truth gets co-opted into an agenda for creating citizens, Truth is the first casualty, but down the line the civilization gets harmed by the collateral damage. The City of God must never get confused with the City of Man, for the good of both.

But. . . Christians are also called to love particular places, and invest in those around them. We don’t live disembodied lives, we live as unique people in unique contexts. To hate and denounce the history of one’s country, or merely to live apart from it in a disembodied state to me seems akin to hating one’s own body. I don’t appreciate the whitewasher of our country’s sins, but his fault is almost always childlike, like the 8 year old who believes that the sports team he roots for always wears the white hat. I have much less stomach for the cynical debunker of everything, of the professor who only seeks to get students not to believe in anything, in order that they might believe only in the professor.

A third type exists, seen in what I suspect may be the trend in high school history textbooks today. This path seeks to uncritically praise other cultures (especially non-western cultures) while giving hefty criticism to one’s own (I have seen this with my oldest son’s textbook). This has the appearance of humility, i.e. “think of others as better than yourselves.” But I think it falls short of that, for it’s not rooted in an actual love of one’s own place. The “virtue” comes at far too cheap a price. This approach reminds me of the teenager who thinks that his parents are hopelessly stupid — if only we could be like this family, or that family, or any other family but their own. In other words, this view falls fails as an intellectually mature perspective.

Christian teachers do not have a duty to “see the best side of everything,” but they should encourage a healthy sense of appreciating where they are, for it is where God has placed them. We must come to terms with our country just as we must come to terms with ourselves. But hating oneself is not Christian. St. Francis used the term “Brother Ass” for his body/himself. Chesterton made the great point that, like a donkey, our bodies can be stubborn, stupid, foolish, and even willfully spiteful at times. But how could one really hate a donkey? Just look at that face!

The term, and the attitude seem appropriate to have towards one’s country. “No one hates his own body” (Eph. 5:29). I am guessing that just about every nation could qualify for the moniker, “Brother Ass.” I confess I don’t know exactly what this means in light of our past with slavery, Native Americans, and so on. I also couldn’t say how African-Americans, for example, might react to my proposed metaphor. But for now . . . it will serve as a place for me at least to start.

Dave