NGreetings,

After 8 sessions, this week we wrapped up our own in class Peloponnesian War Game, which the seniors do every year with this unit. We divided the class into five different teams:

– Athens – Chios (Athenian Ally)

– Sparta – Corinth (Spartan Ally)

– Persia, the Wild Card

Each of the years this game has been played I have seen slightly different outcomes each time. A usual pattern, however, has Athens try and keep a tight leash on Chios to prevent them from rebelling (which Chios, if it wants to win big, must do). Persia usually wants to sponsor Chian independence and use their military for themselves. Thus, Athens becomes Persia’s clear enemy.

This year Persia ended up as probably the biggest winner, with Chios and Corinth scoring victories as well, albeit lesser ones. Both Athens and Sparta ended up destroyed.

In our debrief of our game, we touched on a few key concepts. . .

- I admitted to the class that Athens has the hardest job of any of the combatants. At the start of the game no one likes them and their ally has a strong incentive to rebel. With all of the power and money, they are vulnerable. The only way Athens can win big is through ruthlessness. If they wish to ‘guarantee’ survival, their only other option is “repentance” and generosity right from the start.

- Most Athenian teams don’t realize this at the start of the game, however, and initially pursued a “strong” course of action. Then later they attempted to be nice to their ally, but by then it was too late. A middle course of action usually ends up in defeat for Athens.

- Sparta too had the dilemma of how to utilize its ally. In the end they trusted them too much and paid for it dearly. How one can deal with allies that don’t like you is something we discussed, and something that faces us know in the mid-east.

The outcome of our own war-game resembled the actual war in a variety of ways. Though Sparta won the actual conflict, their victory doomed them to eventual defeat as the war both exhausted them and stretched them too thin in victory.

In the end, I hope the students had fun, and I hope they saw the connections between economics, diplomacy, and fighting

Last week we had a discussion on the idea of fringe opinions and whether or not they benefit democracy. This question came from their homework on Thucydides’s famous passage on the revolution in Corcyra during the Peloponnesian War. Among some of the ideas usually put forth are:

1. Fringe opinions are generally bad, but inevitable if you want to have a democracy.

2. Fringe opinions are not bad or good because they have no impact. The vast meat-grinder that is American society softens whatever fringe opinion comes along before it goes mainstream.

3. Fringe opinions are bad, because those who hold then generally are not open to debate, dialogue, and compromise, all of which are essential to a democracy.

4. Radical fringes usually harm no one but a select few and pose no real threat normally. But in times of great national stress or emergency, they become much more dangerous, as their appeal grows exponentially.

We also discussed what we meant by “fringe opinion.” Is what makes an opinion “radical” the idea itself, or the number of people who espouse it? Can the majority hold a “fringe” opinion?

Should any safeguards be taken against fringe opinions? Many European nations ban the Nazi party, for example, but not the United States.

Obviously we do not face a civil war to the death in our midst, and are nowhere close to the polarization Greece experienced during the Peloponnesian War. But do have any reason for concern? These graphs might give us pause. The first shows the increase of straight party voting over the years, that is, the increase of Democrats only voting with Democrats and Republicans with Republicans.

The second shows the ideological distance between the parties. . .

And finally, the rise of presidential Executive Orders. If Congress stops working the rise of executive power seems inevitable. . .

Many thanks!

Dave Mathwin

Here is the text the students worked through:

The following is from Thucydides, who comments on the revolution in Corcyra in Book 3, chapter 8

For not long afterwards nearly the whole Hellenic world was in commotion; in every city the chiefs of the democracy and of the oligarchy were struggling, the one to bring in the Athenians, the other the Spartans. Now in time of peace, men would have had no excuse for introducing either, and no desire to do so; but, when they were at war, the introduction of a foreign alliance on one side or the other to the hurt of their enemies and the advantage of themselves was easily effected by the dissatisfied party.

71 And revolution brought upon the cities of Greece many terrible calamities, such as have been and always will be while human nature remains the same, but which are more or less aggravated and differ in character with every new combination of circumstances. In peace and prosperity both states and individuals are actuated by higher motives, because they do not fall under the dominion of imperious necessities; but war, which takes away the comfortable provision of daily life, is a hard master and tends to assimilate men’s characters to their conditions.

When troubles had once begun in the cities, those who followed carried the revolutionary spirit further and further, and determined to outdo the report of all who had preceded them by the ingenuity of their enterprises and the atrocity of their revenges. The meaning of words had no longer the same relation to things, but was changed by them as they thought proper. Reckless daring was held to be loyal courage; prudent delay was the excuse of a coward; moderation was the disguise of unmanly weakness; to know everything was to do nothing. Frantic energy was the true quality of a man. A conspirator who wanted to be safe was a recreant in disguise. The lover of violence was always trusted, and his opponent suspected. He who succeeded in a plot was deemed knowing, but a still greater master in craft was he who detected one. On the other hand, he who plotted from the first to have nothing to do with plots was a breaker up of parties and a poltroon who was afraid of the enemy. In a word, he who could outstrip another in a bad action was applauded, and so was he who encouraged to evil one who had no idea of it. The tie of party was stronger than the tie of blood, because a partisan was more ready to dare without asking why. (For party associations are not based upon any established law, nor do they seek the public good; they are formed in defiance of the laws and from self-interest.) The seal of good faith was not divine law, but fellowship in crime. If an enemy when he was in the ascendant offered fair words, the opposite party received them not in a generous spirit, but by a jealous watchfulness of his actions.72 Revenge was dearer than self-preservation. Any agreements sworn to by either party, when they could do nothing else, were binding as long as both were powerless. But he who on a favourable opportunity first took courage, and struck at his enemy when he saw him off his guard, had greater pleasure in a perfidious than he would have had in an open act of revenge; he congratulated himself that he had taken the safer course, and also that he had overreached his enemy and gained the prize of superior ability. In general the dishonest more easily gain credit for cleverness than the simple for goodness; men take a pride in the one, but are ashamed of the other.

The cause of all these evils was the love of power, originating in avarice and ambition, and the party-spirit which is engendered by them when men are fairly embarked in a contest. For the leaders on either side used specious names, the one party professing to uphold the constitutional equality of the many, the other the wisdom of an aristocracy, while they made the public interests, to which in name they were devoted, in reality their prize. Striving in every way to overcome each other, they committed the most monstrous crimes; yet even these were surpassed by the magnitude of their revenges which they pursued to the very utmost,73 neither party observing any definite limits either of justice or public expediency, but both alike making the caprice of the moment their law. Either by the help of an unrighteous sentence, or grasping power with the strong hand, they were eager to satiate the impatience of party-spirit. Neither faction cared for religion; but any fair pretence which succeeded in effecting some odious purpose was greatly lauded. And the citizens who were of neither party fell a prey to both; either they were disliked because they held aloof, or men were jealous of their surviving.

Thus revolution gave birth to every form of wickedness in Greece. The simplicity which is so large an element in a noble nature was laughed to scorn and disappeared. An attitude of perfidious antagonism everywhere prevailed; for there was no word binding enough, nor oath terrible enough to reconcile enemies. Each man was strong only in the conviction that nothing was secure; he must look to his own safety, and could not afford to trust others. Inferior intellects generally succeeded best. For, aware of their own deficiencies, and fearing the capacity of their opponents, for whom they were no match in powers of speech, and whose subtle wits were likely to anticipate them in contriving evil, they struck boldly and at once. But the cleverer sort, presuming in their arrogance that they would be aware in time, and disdaining to act when they could think, were taken off their guard and easily destroyed.

Now in Corcyra most of these deeds were perpetrated, and for the first time. There was every crime which men could commit in revenge who had been governed not wisely, but tyrannically, and now had the oppressor at their mercy. There were the dishonest designs of others who were longing to be relieved from their habitual poverty, and were naturally animated by a passionate desire for their neighbour’s goods; and there were crimes of another class which men commit, not from covetousness, but from the enmity which equals foster towards one another until they are carried away by their blind rage into the extremes of pitiless cruelty. At such a time the life of the city was all in disorder, and human nature, which is always ready to transgress the laws, having now trampled them underfoot, delighted to show that her passions were ungovernable, that she was stronger than justice, and the enemy of everything above her. If malignity had not exercised a fatal power, how could any one have preferred revenge to piety, and gain to innocence? But, when men are retaliating upon others, they are reckless of the future, and do not hesitate to annul those common laws of humanity to which every individual trusts for his own hope of deliverance should he ever be overtaken by calamity; they forget that in their own hour of need they will look for them in vain.

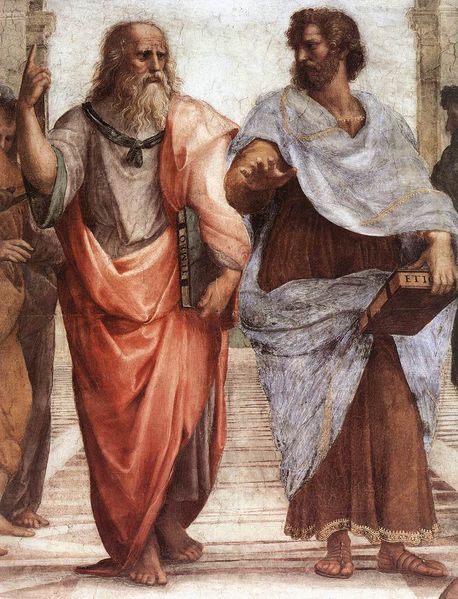

legal scholar and author Jeffrey Rosen, who has written extensively on technological change and the constitution. While this was a detour of sorts, our discussion of Plato does relate. Do we see the Constitution as an absolute, fixed, standard, no matter what changes around it? Or, do we see the Constitution having certain key principles, that apply differently given the context of the times? The first view obviously would have more in common with Plato, the second has more of an Aristotelian influence. Plato, of course, would not want “Truth” to be influenced by context, as that would mean that truth had to be bound up in “matter,” which had inherent inferiority to “spirit.”

legal scholar and author Jeffrey Rosen, who has written extensively on technological change and the constitution. While this was a detour of sorts, our discussion of Plato does relate. Do we see the Constitution as an absolute, fixed, standard, no matter what changes around it? Or, do we see the Constitution having certain key principles, that apply differently given the context of the times? The first view obviously would have more in common with Plato, the second has more of an Aristotelian influence. Plato, of course, would not want “Truth” to be influenced by context, as that would mean that truth had to be bound up in “matter,” which had inherent inferiority to “spirit.”