Greetings,

This week we continued our look at Rome by looking at the establishment of the Republic in 508 B.C., and how that related to power sharing between Patricians and Plebians.

We can see a variety of similarities between Rome’s revolution, and our own, and this comparison surely would have pleased on our own founding fathers. But that does not necessarily mean that we should see democracy, in the technical sense of the word, in either time. The Romans came to object to their kings for the following reasons:

1. Arbitrary and Personal Power

Ultimately, Roman kings did not have to use law as the basis of their rule. They could, in the end, do as they pleased. Law had the advantages of being public and stable. Rulers could now be accountable to something outside of themselves

2. Secret Power

When kings make decisions, they often do so in secret, perhaps with a few advisors. Whether he took counsel or not, the reasons behind the decision would be unknown. The Romans wanted to create a government where decisions got made in an open forum, with open debate.

3. Concentrated Power

In the pure monarchies all power flows from one source at all times. The Romans took political power and divided it among various offices and branches. They then made sure that they always had more than one person serving in a particular office. Finally, each of their offices had only one year terms, and while they did not outright forbid serving multiple terms, they frowned sternly upon it.

The best way to think about what the Romans did is to go to the technical definition of a Republic – a “Res Publica” – a “Public Thing.” Laws, expectations, debates, all these things were out in the open for the Romans. We should not expect to see the kind of democracy that Athens practiced here, though Rome’s republic certainly had democratic elements. Their main priority lay in making sure that the government was “public” — open to debate, open to observation, etc.

This does not mean that the Romans established a democracy, though they did broaden the base of political power. Still, for the most part power stayed in the hands of the Patricians, Rome’s aristocracy. This happened not necessarily by design, but certain factors heavily contributed to it.

- The Senate (comprised almost entirely of Patricians) had almost complete control of War and Peace. Rome was often at war, and often won, which naturally enhanced the prestige and power of the Senate. We have seen in our own democracy that whenever a foreign policy crisis strikes, domestic issues invariably take a back-seat. Such was the relationship between the Assembly and the Senate in Rome.

- As we noted last week, Rome was strongly traditional in its cultural leanings, and the Patricians had a vested interest in maintaining tradition.

- The differences in wealth between Patricians and Plebians remained modest for most of the Republic’s history. As we shall see in a few weeks, when this begins to change the Patricians faced more challenges to their power.

- Finally, nothing succeeds like success. For centuries, Rome grew and prospered under the general guidance of patricians.

The argument went deeper than this, however. At root the question of, “What is Rome,” ran underneath the surface arguments. For Patricians, Rome was an idea. Rome’s ideals made Rome great, and Rome could only stay great if the people who led had dedication to those ideals. For Plebians, Rome’s people made Rome great, and so Rome’s people deserved a greater share of power. This tension would bubble beneath the surface for a long time, and how Rome eventually dealt with the problem would contribute to the unraveling of the Republic itself.

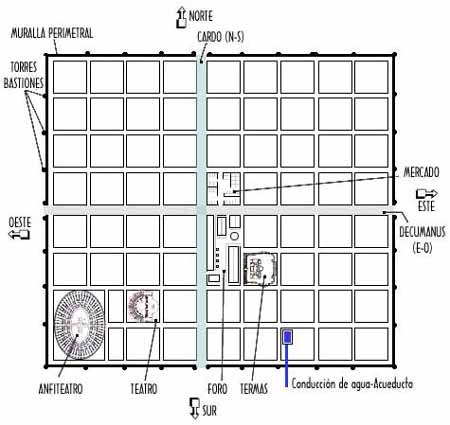

We also looked the basic grid plan of Roman cities, and discussed what they reflect about Rome.

Nothing shocks us here, but the methodical nature of the design reflects a few key Roman values, such as simplicity and unity. The design pushes people toward the center, with an emphasis on togetherness. The grid plan may also hint at the idea of equality, or at least equality under the law.

As Rome expanded they “cut and pasted” their city design into the conquered areas. Rome valued habit, tradition, and togetherness. They tended to look down on “going your own way” in general, and as we might expect, in the army as well. The key to their military success lie in the fact that everyone stayed together, everyone did what they were told.

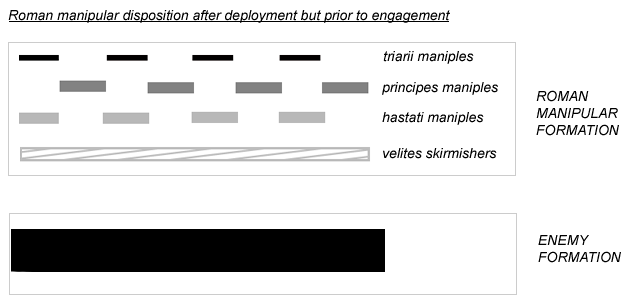

The values that went into the formation of their government and city design also went into their army, whether consciously or not. The standard Roman military formation looks somewhat like its city design, with the men spread out in checkerboard fashion:

Rome’s design gave them more flexibility of movement in the field, but each “maniple,” or individual grouping, had a high level of discipline. This clip below, manages in 1:30 to show some of those values (warning: not bloody, but violent).

Greece, being a more individualistic society, had a long history of heroic individuals. In Roman stories, the hero is Rome itself. The clip illustrates a few key ideas along these lines:

- When the whistle blows, the front lines move back, and others move up. Normally soldiers would fight in front for much longer than the clip shows, but the principle is clear: we all share the burden equally.

- Roman tactics, like their other values, were simple. Block with the shield, strike with the sword around the enemy’s waist, step back into formation. With this basic move they conquered much of the world around them.

- No one gets out of line. They do not tolerate even the successful “hero.” Rome itself will always get the credit. The cohesiveness of the line reflects the cohesive nature of their society. And these cohesive military formations gave them a great advantage over other less cohesive, more heroically oriented tribes surrounding them. In these kinds of circumstances, Rome simply did not lose.

Here is a clip from Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus, where you see the Roman army advance in their maniples. The message seems to be that the city of Rome itself has come to fight as they fan out into their grid pattern.

Next week we will begin to look at Rome’s conflict with Carthage, a struggle that would define the destinies of both societies.

Have a great weekend,

Dave