My grandfather fought in W.W. II for the 101st Airborne. He took part in the invasion of Arnhem in September 1944, a campaign immortalized by the book/movie A Bridge too Far. One story he related dealt with the British love of tea. If the British/American plan had a chance of success allied forces needed to move as fast as possible to seize several key bridgeheads across the Rhine River. But at around 4:00, British units pulled over on the side of the road and had their tea for 15 minutes, driving their American counterparts nuts. How anyone could justify teatime at such a time baffled them.

I suppose the British might have responded along the lines of, “If we don’t stop for tea at 4:00, then the Nazi’s have already won!”

Tensions between tradition and the exigencies of the moment have always been with us. In every instance where it arises good arguments exist on both sides that invariably go something like

- We must change in order to survive, vs.

- If we change the wrong things, or change too much, it won’t be “we” that survive but another sort of society entirely.

I very much enjoyed the many strengths of Basil Liddell Hart’s Scipio Africanus: Greater than Napoleon. My  one quibble with the book is his failure to tackle this dilemma as it relates to Rome in the 2nd Punic War.

one quibble with the book is his failure to tackle this dilemma as it relates to Rome in the 2nd Punic War.

But first, the book’s strengths . . .

The title indicates that Hart might indulge in a bit of hero-worship, but I have no problem with this in itself. First of all, he lets the reader know from the outset where he stands. And, while her0-worship books have inevitable weaknesses, I very much prefer this approach to writing that equivocates to such a degree so that the author says nothing at all.

Hart’s book also reverses the common tendency to glorify the romantic loser. We love Robert E. Lee, but Grant, well, he’s boring. We love Napoleon and see Wellington as . . . boring. Historians of the 2nd Punic War have devoted an overwhelming amount of attention to Hannibal. His march through the Alps and his enormously impressive successes at Trebia, Trasimene, and Cannae have inspired military minds for centuries. Sure, Rome won in the end, but for “boring” reasons like better political structure and more human resources–just as many assume Grant won not because of what he did, but because of the North’s “boring” industrialization and economy.

But surely Hannibal’s defeat had something to do with Scipio himself, especially seeing as how a variety of other Roman commanders failed spectacularly at fighting the wily Carthaginian. To add to this, if you knock out the champ, doesn’t that mean that we have a new champion?

Liddell Hart gives us some great insights in this book.

Those familiar with Hart’s philosophy know that he constantly praised the value of what he called the “indirect approach” to war, both tactically and strategically. Rome at first tried the direct approach with Hannibal and lost badly. Then with Fabius they practiced what some might call “no approach” with a debatable amount of success. Scipio struck a balance. After assuming command he fought the Carthaginians, but not in Italy. He took the fight to Carthage’s important base in Spain. He fought against Carthaginian troops with Carthaginian commanders, but avoided Hannibal.

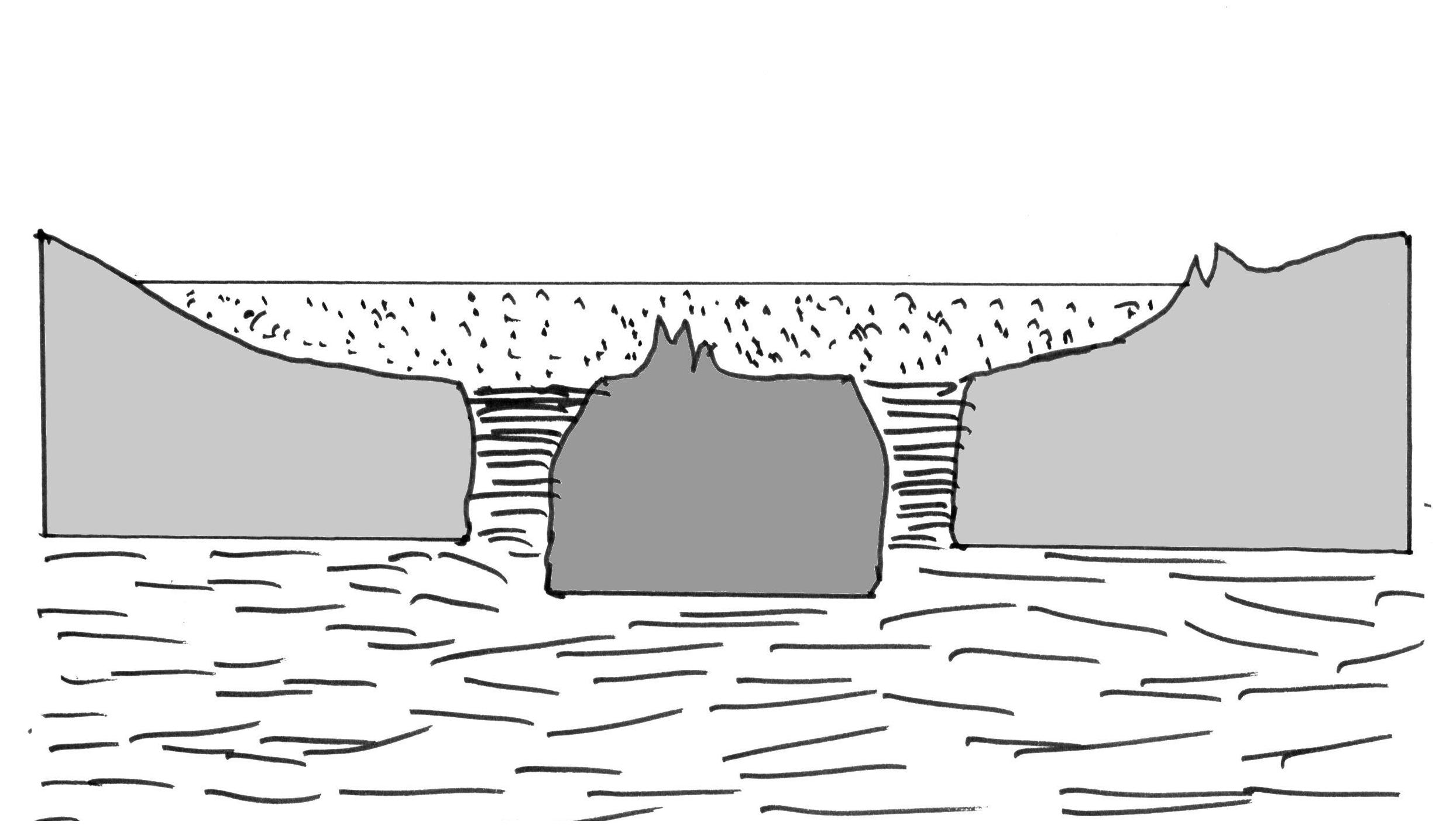

I have no great military knowledge and no experience, but Hart’s concise explanation of Scipio’s maneuvering in Spain impressed me greatly. His “double envelopment” move at the Battle of Ilipa against a numerically superior foe was an inspired stroke:

But I found Scipio’s diplomatic and grand-strategical vision more impressive. Hart admits that Hannibal had the edge over Scipio in tactics, but I feel that most overlook or excuse Hannibal’s deficiencies at accomplishing his strategy of prying allies away from Rome. In a very short time Scipio turned the tables completely in Spain, giving Rome a foundation on which to build a Mediterranean empire. Unlike other great commanders such as Napoleon and Alexander, and even Hannibal, Scipio never had full control of his forces or his agenda. He accomplished more than most any other commander while navigating more difficult political terrain. He established the basis militarily and diplomatically for Rome’s preeminence in the Mediterranean. He deserves the praise Hart heaps on him.

However, the ‘hero-worship’ part of the book needs addressing. Hart writes with much more balance than Theodore Dodge, who wrote about Scipio’s counterpart Hannibal. But he makes the same kind of mistakes as Dodge by dismissing some of the political realities Rome faced because of Scipio’s success. In sum, Hart has no appreciation for the tension between Roman tradition and Roman military success at the heart of this conflict.

Rome’s Republic had no written constitution. It ran according to tradition. The bedrock principles were:

- Sharing power amongst the aristocratic class

- Yearly rotation of offices

- Direct appeals to the people smelled of dictatorship

- No one stands out too much more than anyone else. They sought more or less to divvy up honor equally.

- You wait your turn like everyone else. No one jumps in line ahead of anyone.

From the start of his career Scipio challenged nearly all of these principles in a dramatic way. Hart himself admits that:

- He ‘level-jumped’ to high office far earlier than anyone else, breaking the unofficial rules that held things together.

- He frequently received his support directly from the people against the wishes of the aristocracy

- He at times used religious claims to boost his appeal for office, which the people responded to over and against the scowls of the aristocracy.

- In defeating Hannibal he raised his status far higher than any other Roman of his day. This can’t be held against him obviously, but everyone noticed.

Of course we naturally have a distaste for aristocracy and so does Hart, who loses no opportunities to cast aspersions on Cato, Fabius, and other grumpy, jealous old men.

But . . . by any measure the Roman Republic ranks as one of the more successful governments of all-time. While they were not close to fully democratic, they had many democratic elements, and still managed annual, peaceful transitions of power across all levels of government for (at the time of the 2nd Punic War) for 300 years. Judged by the standards of their day, some might even label them as “progressives.” They had a great thing going and we should not rashly blame them for wanting to protect it.

During the war itself one can easily agree with Hart and his roasting of Fabius and especially Cato the Elder. But events in the generations after the 2nd Punic War show that Scipio’s enemies may have been at least partially on to something. Within 30 years of their victory, the Republic had major cracks. After 75 years, the Republic began its collapse. In time the Republic could not even pretend to contain Marius, Sulla, Crassus, Pompey, and Caesar. One could argue that Scipio in an indirect way set the stage for this.

Hart wrote a very good book, but not a great one. I wonder what he would have thought of the British soldiers at Arnhem. The disruption Rome suffered as a result of the 2nd Punic War had a lot more to do with Hannibal than Scipio. And yet, Scipio played some part, albeit a small one. Was it worth it? Could it have reasonably happened differently? Hart doesn’t say, and leaves us to wonder.