I appreciate writers with strong points of view who take big swings. I wince at those who swing and miss badly, but I can usually admire the effort. I can usually forgive those whom I think get things wrong if I perceive that they try to see different sides of an issue. For example, I think Arthur Miller gets the Puritan witch trials mostly wrong in The Crucible, but he still writes a good play, because he clearly understands the strengths of the Puritans and what virtues might have led them down a wrong path. One can see good and bad, but misinterpret the place and balance of each in a particular epoch. What sends me to an early grave are those who see different possible sides of a civilization and interpret all sides negatively as it suits their purpose.

For example, the Old Testament has come under deconstructive criticism for the last 150 years or so, as various Germans have tried to reduce the authority of the text by pointing out two contradictory things:

- The texts are a mashup of various Sumerian, Babylonian, Egyptian etceteras that contradict each other at a variety of places, or

- The text is the work of a devious editor, carefully culling and sculpting a single product from a variety of sources, who tries to present a Potemkin village of unity, and hence, authority. Thank goodness for all those 19th century Germans, who, after millennia of wool pulling by said devious editors, finally exposed their wicked ways.

In other words, the Old Testament is made to seem meaningless for completely opposite reasons. Choose whatever view of the text you like–you can’t win either way. Or, you can have any color you like, as long as it’s black.

The Middle Ages, a relatively recent battleground for modern political controversies, also gets it with both barrels for different reasons. On the one hand,

- They were strongly authoritarian and narrow, throttling heretics and witches, science and philosophy, at their leisure, or

- That out of weakness, unable to stamp out pagan gods and folkways, they stooped to a muddy, broad syncretism in culture and religion.

Hypothetically they could resemble one or the other, but not both at the same time.

Every civilization must have its “narrow” traits, for we must define ourselves in some particular way in order to distinguish from others. And, every civilization has its broad traits, for every human friendship, marriage, or political association will involve some kind of “mixing” and compromise. Intolerance and tolerance both have their place–just make sure you have the proper places for them. The historian then, must construct a narrative by attempting to see how and why civilizations made their choices, by attempting to find their modus operandi, and work outwards from there. If they fail to see this central point of departure, they will conflate things in all the wrong ways.

Ultimately I found myself conflicted by John Williamson’s The Oak King, the Holly King, and the Unicorn, which attempts to explain medieval symbolic thought and culture. Williamson knows many facts, and I found some of his observations about the famous unicorn tapestries illuminating. But at times, he commits the worst of errors, stooping to sheer imbecility.

For example . . .

As the title indicates, he devotes a portion of the book to showing the role of oak trees in the medieval mind. Now, most anyone who has seen an oak tree and noted their size and age, might easily guess as to why such wondrous things might fascinate anyone. But for his answer as to why the medievals valued oaks, Williamson quotes approvingly from Joseph Frazer, who writes,

“Long before the dawn of history, Europe was covered with a vast primeval forest which must have exercised a profound influence on the thought as well as the life of our rude ancestors who dwelt dispersed under the gloomy shadow or in the open glades and clearings of the forest. Now, of all the trees which composed those woods the oak appears to have been the most common and the most useful.” Thus [writes Williamson], it was natural enough that the oak should loom so large in the religion of a people who “lived in oak forests, used oak timber for building, oak sticks for fuel. “

So–the “rude” ancestors who lived in a “primeval” forest “must have”–surely they must have–had a fascination with oaks because of the particular geography they inhabited. They then passed this fascination on down to their ancestors. Ok, I think this wrong-headed, but it is a coherent point of view.

But, in the next few paragraphs, Williamson then shows the universality of the importance of oaks, citing that the Greeks and the Norse both gave a high place to oak trees also–neither of which lived in geographies with dense “primeval” forests. So they “must have” been fascinated with oaks because they were not so plentiful where they lived? Almost on the same page, seemingly without realizing, Williamson

- Shows that the medievals got their ideas from “rude” ancestors in their one, narrow, backward part of the world, and

- They borrowed from universal, pre-Christian “pagan” ideas from more developed civilizations with more developed mythologies.

It baffles me, and keeps me up late at night clacking on the keyboard, that Williamson cannot see the inherent contradiction.* To make matters worse (if possible), Williamson never wonders why a similar symbolic meaning for oak trees has permeated different cultures across time and space. His curiosity extends only to the facts, and not to the reason for, or the meaning of, the facts, despite the fact that anyone who has seen an oak tree can make a better guess than he. This too I find incomprehensible and indefensible, and errors of approach like this find their way into different aspects of the book.

Williamson has strengths as an author. Many see the medievals lack of experimentation as an inherent weakness. Williamson sees it as at least a semi-deliberate choice, and I say bravo to him for that. Medieval people preferred bringing things together rather than pulling them apart. They constructed, while we deconstruct. Science, or certain kinds of science, has the marvelous ability to break things down into smaller components–no doubt a useful skill at times. Williamson rightly recognizes, however, that science cannot give the kind of cohesion that medievals sought. The medievals constructed cohesion and meaning through story and symbol, realms where science has little to no part to play.

I also appreciated Williamson’s insights into holly, which strangely I had never thought of before, despite a variety of Christmas hymns that reference holly. Every culture has more or less associated winter with death, but evergreens remind us of the promise of new life even in the midst of death. The red berries on holly trees add extra meaning, with a foreshadowing of Christ’s shed blood even in His birth. Williamson then deftly turns to an interpretation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight with insights that I had thought of before related to oak and holly, and the interplay between winter and summer, death and life, that mirrors the tension between the Green Knight and Gawain.

Kudos to Williamson for seeing that medieval people, and most any other pre-modern people, consciously constructed their world through participation. They of course concerned themselves to a point with belief in a more abstract sense. But participation mattered much more to them, that is, entering into the reality professed through ritual reenactment. He applies this pattern to medieval thoughts about unicorns. I address whether or not unicorns actually physically existed in another post. For us “literal” existence of the unicorn is what really matters, but not so for medieval people. For them, the meaning of the unicorn was its reality. We might understand this, if we say that “obviously Santa Claus exists.” We know what he looks like, and how he is supposed to act. We know that when he steps outside of certain bounds, he will be unmasked as “not really Santa.” In this sense, most of us interact with Santa every year.

“Ah,” one might say, “but we can visit Santa at the mall, whereas we cannot hunt unicorns unless they actually exist somewhere.”

This is certainly a fair point.

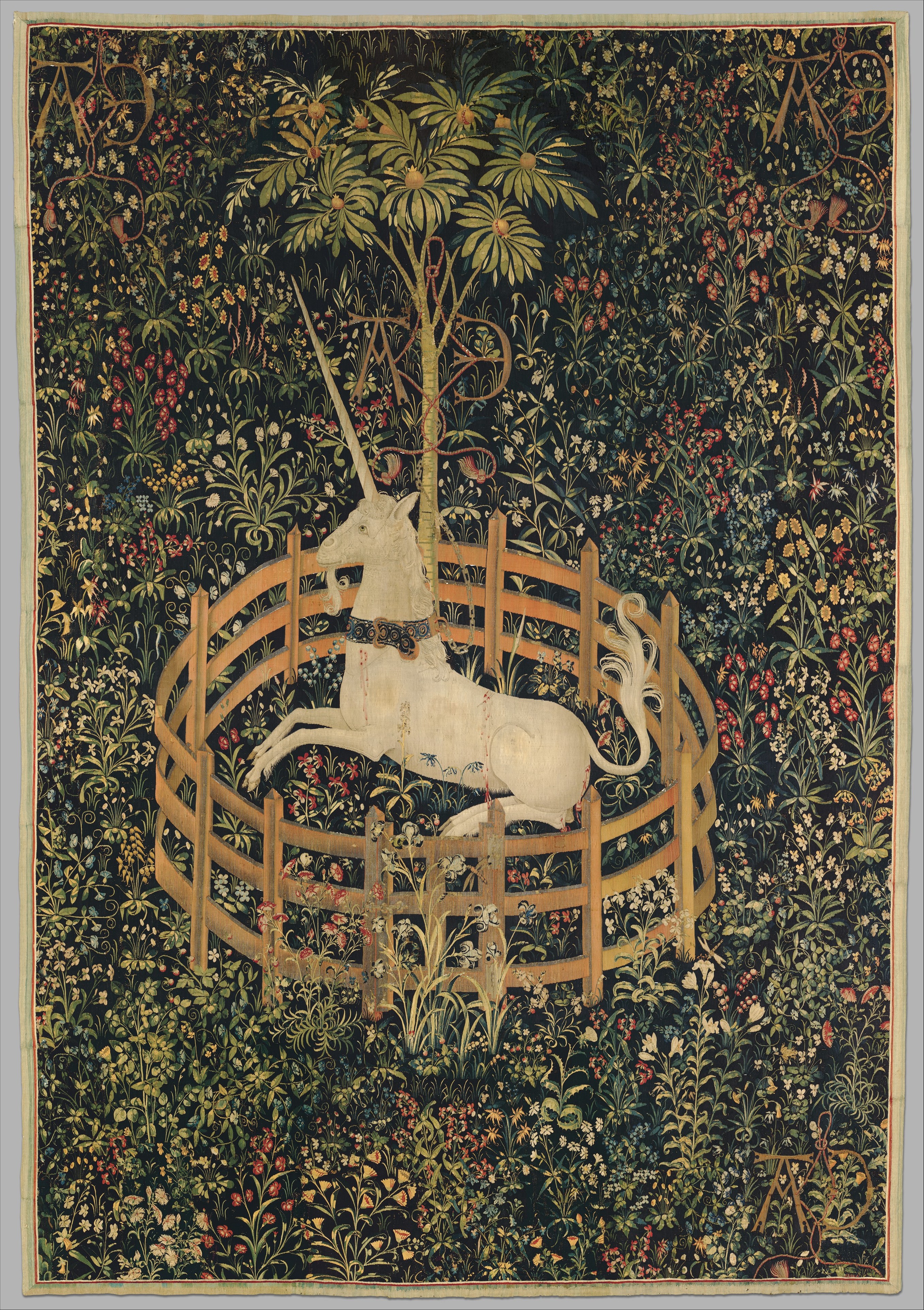

But given the Christological symbolism of the unicorn hunt–the ‘wooing’ of God through beauty, the death of the Christ figure, etc.–medieval people entered into the hunt through participation in the liturgical cycle. Even supposing that unicorns physically existed and that medieval people really hunted them (this is not my view), the unicorn hunt tapestries did not depict an actual hunt, for the final frame has the unicorn resurrected, enclosed in a wedding band of sorts, “married” to the people as an image of salvation, it’s wounds still visible just as Christ’s.

So despite my heavy criticism of Wiliamson earlier, he understands and appreciates certain aspects of medieval thought better than most. But as mentioned earlier, he has no larger frame into which he can think about the bigger, more important questions of why Christians used classical and mythological sources as they did.

Those who seek for a “pure” Christianity unmixed with any particular culture will seek for a long time. Some aspects of Mosaic law resemble laws from Babylon and other cultures. Certain parts of Genesis seem written at least partly in response to surrounding creation narratives. Some decry the “Greek” influence on the early church fathers but Judaism and Greek culture had interacted for centuries prior to Christ’s coming, at least as far back as the Septuagint translation of the Old Testament, from which the Apostles quoted in the New Testament. Very early in the church’s history depictions of Christ took on some Roman forms and tropes.

True, the Church warred against the pagan culture around them, showing their “intolerance.” But almost all of our written sources from the classical world come down to us only because monks copied, preserved, and protected those manuscripts. Many are aware of this fact, yet few take it into their heads why the Church encouraged such behavior. It takes quite a leap of faith to imagine monks scattered throughout saying something like, “The Church has grown stronger and more numerous through the blood of countless martyrs for three centuries. We have done what no other civilization accomplished and conquered Rome. But we have no confidence in our message or our faith. Let’s copy their manuscripts, and incorporate their artistic style, and maybe if we’re lucky they’ll hear us out and convert.” Most sane people look at Dante, for example, and marvel at his integration of biblical and contemporary history, and classical and Christian culture. We don’t assume that he made Virgil his initial guide due to the weakness of his faith. We should not do so with the civilization that produced him.

One must decide how to interpret medieval incorporation of pre-Christian ideas, whether they acted out of weakness or confidence.

Every reason exists within the history of the church to see this move as one of confidence, a consistent outworking of bedrock theological principles.

If, as the Creed declares, that all things were created in, through, and by Christ, then we might naturally expect creation to witness to that fact. In the 3rd century Origen wrote that,

The apostle Paul teaches us that the invisible things of God may be known through the visible, and that which is not seen may be known by what is seen. The Earth contains patterns of the heavenly, so that we may rise from lower to higher things.

As a certain likeness of these, the Creator has given us a likeness of creatures on earth, by which the differences might be gathered and perceived. And perhaps just as God made man in His own image and likeness, so also did He make remaining creatures after certain other heavenly images as a likeness. And perhaps every single thing on earth has something of an image or likeness to heavenly things, to such a degree that even the grain of mustard, which is the smallest of seeds, may have something of an image and likeness in heaven.

Dionysius the Areopagite later wrote (perhaps 6th century AD?) concerning hierarchies and their images that,

The purpose, then, of Hierarchy is the assimilation and union, as far as attainable, with God, having Him Leader of all religious science and operation, by looking unflinchingly to His most Divine comeliness, and copying, as far as possible, and by perfecting its own followers as Divine images, mirrors most luminous and without flaw, receptive of the primal light and the supremely Divine ray, and devoutly filled with the entrusted radiance, and again, spreading this radiance ungrudgingly to those after it, in accordance with the supremely Divine regulations.

We can add St. Maximos the Confessor (7th century) to our query, one of the very greatest minds of the Church. He picked up these threads and developed the idea of the Logos and the logoi, that is, how the diversity of things coheres in the Logos/God-Man (without confusing or diminishing any particularity). One commentator writes,

The supreme unity of the logoi is realised in and by the Logos, the Word of God himself which is the principle and the end of all the logoi. The logoi of all beings have in effect been determined together by God in the divine Logos, the Word of God, before the ages, and therefore before these beings were created; it is in him that they contained before the centures and subsist invariably, and it is by them that all things, before they even came into existence, are known by God. Thus every being, according to its own logos, exists in potential in God before the centuries. But it does not exist in act, according to this same logos, except at the time that God, in his wisdom, has judged it opportune to create it. Once created according to its logos, it is according to this same logos again that God, in his providence, conserves it, actualises its potentialities and directs it toward its end in taking care of it, and in the same way by his judgment he assures the maintenance of its difference, which distinguishes it from all other beings.

Here–and elsewhere–lies the foundation for how to deal with the pagan past. It need not be wholly good, for “all the gods of the nation are demons” (Ps. 96:5). But, pagans also are made in the image of God, and so the Church knew that fractals of the Logos lay there as well. Here lies an entire framework for medieval people to examine and integrate the past. One might debate what to include, and what to exclude, but clearly they knew the necessity of both.

As we approach Epiphany, the pattern for how to see as the medievals saw shows itself in the Scriptures and prayers of the Church. The magi, likely from Babylon, looked to astrology, and a star guided them to the maker of stars. “Those who worshiped the stars were taught by the stars to worship You, o Sun of Righteousness” (Christmas troparion). The “Sun” here is not a typo. God uses their idolatry and affirms something of it–that’s tolerance, if you like. But the Church also shows where the magi fall short, and transforms their false faith into a pointer to Truth, the Sun who is the Son. At a certain point, one cannot tolerate paganism and remain a Christian.

To my mind, this is the project of Christendom in a nutshell.

Dave

*Any student of mine, past or present, actually reading this post who wants to get revenge on me in any way . . . you need not worry about putting a tack on my chair, or not turning in homework, or talking in class. You simply need to go onto graduate school, get an advanced degree in Cultural Studies (or something like that), get published, and write the kind of nonsense as Williamson has here. I guarantee you will make me question the very reason for my existence.

When Williamson strays from the details and attempts to draw broad conclusions, he makes blood boiling mistakes dealing with Christian and pagan distinctives. For example, on page 98, he compares Christ to “other vegetation deities . . . such as Narcissus and Adonis.” Narcissus and Christ?! I ask you!