Greetings,

Most of us would shudder at the thought of visiting a medieval doctor. After all, they bled people to make them well and actually used leeches for treatment of wounds (doctors were actually called ‘leeches’ in the common tongue). This general aversion offers a great opportunity to get a fresh look at medieval people and see what they valued. How they thought about health reflected their deeper beliefs about humanity and the world around them. Hopefully by looking at a very different approach to health we can see the nose in front of our own face, and more accurately understand our own culture.

I remember a conversation I had just after college. A woman asked me what I thought of Eastern medicine, and I replied that I didn’t know much about it, but was wary of the possible non-Christian foundations of eastern approaches. She asked me, “Are you so sure that western medicine has a Christian foundation?” I was struck speechless (a rare occurrence, unfortunately). I had to admit that I had never thought about it before, never seen the nose on my face, so to speak.

In that spirit, I wanted the students to approach the subject with an open mind.

What did they believe?

Just as the medievals based (consciously or no) their society on their perception of the order in the cosmos, so too they thought of health vis a vis man’s place in the universe. It was “holistic” healing in the widest possible sense. Originally, man stood in harmony with the rest of creation, just as Earth did with the rest of the cosmos. Man in harmony with creation meant man in harmony with himself, with his various internal elements of earth, air, water, and blood in harmony.

The Fall disrupted this harmony, and so medicine should seek to restore it, to put the elements back in their right place. This concept of balance, so important in medieval politics, shows itself in medicine as well. Today we have various medical supplements that allow us to go beyond what is natural but for medievals the key was not fighting nature but restoring harmony with it.

Internal harmony had its reflection again in the relationship between the physical and spiritual in our lives. Some mock medieval medicine by arguing that they thought every disease had its cure in prayer. That is not true, but they did believe that one’s mental and spiritual well-being impacted our physical state, and vice-versa.

Their emphasis on the planets probably stands as one of their more perplexing beliefs, and for that reason perhaps most instructive for us.

First, we note that the medievals saw the cosmos as interconnected like a spider web, not one of free- floating entities. Movement in one area effected other areas. Motion in cosmos impacts motion on Earth, which impacts us.

floating entities. Movement in one area effected other areas. Motion in cosmos impacts motion on Earth, which impacts us.

This does not mean that they believed that planetary motion could cause actions on earth. Rather, planetary motion was considered part of the environment in which man operated, and had to account for. Here is Aquinas, for example, on the motion of the heavenly bodies and the limits of its impact. . .

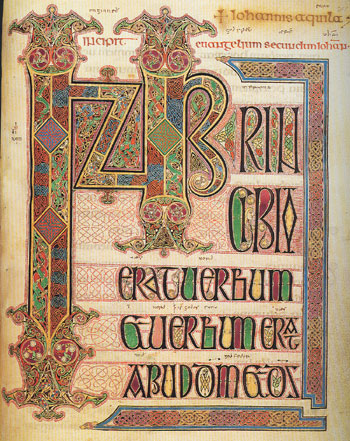

Summa Theologica, Do Planets cause human action?

Objection 1: It would seem that the human will is moved by a heavenly body. For all various and multiform movements are reduced, as to their cause, to a uniform movement which is that of the heavens, as is proved in Phys. viii, 9. But human movements are various and multiform, since they begin to be, whereas previously they were not. Therefore they are reduced, as to their cause, to the movement of the heavens, which is uniform according to its nature.

Objection 2: Further, according to Augustine (De Trin. iii, 4) “the lower bodies are moved by the higher.” But the movements of the human body, which are caused by the will, could not be reduced to the movement of the heavens, as to their cause, unless the will too were moved by the heavens. Therefore the heavens move the human will.

Objection 3: Further, by observing the heavenly bodies astrologers foretell the truth about future human acts, which are caused by the will. But this would not be so, if the heavenly bodies could not move man’s will. Therefore the human will is moved by a heavenly body.

On the contrary, Damascene says (De Fide Orth. ii, 7) that “the heavenly bodies are not the causes of our acts.” But they would be, if the will, which is the principle of human acts, were moved by the heavenly bodies. Therefore the will is not moved by the heavenly bodies.

I answer that, It is evident that the will can be moved by the heavenly bodies in the same way as it is moved by its object; that is to say, in so far as exterior bodies, which move the will, through being offered to the senses, and also the organs themselves of the sensitive powers, are subject to the movements of the heavenly bodies.

But some have maintained that heavenly bodies have an influence on the human will, in the same way as some exterior agent moves the will, as to the exercise of its act. But this is impossible. For the “will,” as stated in De Anima iii, 9, “is in the reason.” Now the reason is a power of the soul, not bound to a bodily organ: wherefore it follows that the will is a power absolutely incorporeal and immaterial. But it is evident that no body can act on what is incorporeal, but rather the reverse: because things incorporeal and immaterial have a power more formal and more universal than any corporeal things whatever. Therefore it is impossible for a heavenly body to act directly on the intellect or will. For this reason Aristotle (De Anima iii, 3) ascribed to those who held that intellect differs not from sense, the theory that “such is the will of men, as is the day which the father of men and of gods bring on” [*Odyssey xviii. 135] (referring to Jupiter, by whom they understand the entire heavens). For all the sensitive powers, since they are acts of bodily organs, can be moved accidentally, by the heavenly bodies, i.e. through those bodies being moved, whose acts they are.

But since it has been stated (A[2]) that the intellectual appetite is moved, in a fashion, by the sensitive appetite, the movements of the heavenly bodies have an indirect bearing on the will; in so far as the will happens to be moved by the passions of the sensitive appetite.

Reply to Objection 1: The multiform movements of the human will are reduced to some uniform cause, which, however, is above the intellect and will. This can be said, not of any body, but of some superior immaterial substance. Therefore there is no need for the movement of the will to be referred to the movement of the heavens, as to its cause.

Reply to Objection 2: The movements of the human body are reduced, as to their cause, to the movement of a heavenly body, in so far as the disposition suitable to a particular movement, is somewhat due to the influence of heavenly bodies; also, in so far as the sensitive appetite is stirred by the influence of heavenly bodies; and again, in so far as exterior bodies are moved in accordance with the movement of heavenly bodies, at whose presence, the will begins to will or not to will something; for instance, when the body is chilled, we begin to wish to make the fire. But this movement of the will is on the part of the object offered from without: not on the part of an inward instigation.

Reply to Objection 3: As stated above (Cf. FP, Q[84], AA[6],7) the sensitive appetite is the act of a bodily organ. Wherefore there is no reason why man should not be prone to anger or concupiscence, or some like passion, by reason of the influence of heavenly bodies, just as by reason of his natural complexion. But the majority of men are led by the passions, which the wise alone resist. Consequently, in the majority of cases predictions about human acts, gathered from the observation of heavenly bodies, are fulfilled. Nevertheless, as Ptolemy says (Centiloquium v), “the wise man governs the stars”; which is a though to say that by resisting his passions, he opposes his will, which is free and nowise subject to the movement of the heavens, to such like effects of the heavenly bodies.

Or, as Augustine says (Gen. ad lit. ii, 15): “We must confess that when the truth is foretold by astrologers, this is due to some most hidden inspiration, to which the human mind is subject without knowing it. And since this is done in order to deceive man, it must be the work of the lying spirits.”

For them, paying attention to planetary motion might be akin to us today paying heed to a weather pattern off the coast of Japan. But again, Aquinas hints at something more than this, something with more weight behind it. C.S. Lewis, a professor of Medieval & Renaissance Literature, used these ideas in his Chronicles of Narnia series, as well as books like Perelandra and That Hideous Strength.

Different planets had different impacts. Of course the planets outside of earth had no sin, so the influence of some was not bad in itself, but often became so when interacting with our own fallen environment.

Saturn — The Infortuna Major

Saturn’s influence tends to make people introspective, moody, and inwardly focused. This makes sense when we realize that the Greek name for Saturn is Cronos, where we get our language for time. The idea here is of one who broods, who navel gazes. Saturn is associated with the “melancholy” personality type. Melancholies can achieve great heights in artistic, intellectual, and spiritual endeavors. Many of our great geniuses likely had this personality. But the danger comes when they live too much inside their own head, isolate themselves, and subject themselves to psychological debilitations like depression.

Jupiter — The Fortuna Major

Jupiter received its name from Jove, the Roman name for Zeus. Hence, Jupiter brings kingly joy. When the king is happy the people feast. People come together and sing, dance, eat, etc. This concept of communal joy was the highest good for medievals, which they associated with the “Sanguine” personality type.

Mars — The Infortuna Minor

Mars of course brings war. The “red planet” is associated with anger, and thus its earthly mirrors can be found in strong ‘Type A’ personalities. What should strike us about Mars being the “Infortuna Minor” is that the medievals did not think war as bad as a nation of isolated brooders. War brings many evils, but a silver lining can be that it does bring people together — and here we see again the medieval “community” emphasis.

Venus — The Fortuna Minor

Venus brings love, and is often linked with romantic love between a man and woman. Again, we have an interesting contrast between their world and ours. For us, nothing can be greater than experiencing romantic love, but for them, nothing was great than “joviality.” Again, we see the community emphasis, and when we step back from romantic love, we see that while it does bring two people together, it also can isolate those two from others around them. Isolated joy between two people cannot match communal joy for the medievals.

The composer Gustav Holst used the medieval ideas about the planets to write a series of compositions. As is appropriate, the best one is “Jupiter.”

All in all, we have more of the medieval world with us than we might realize.

- Some hospitals actually use leeches!

- The current emphasis on a holistic approach to health comes directly from the medieval period

- The focus on health care trying to keep you healthy comes directly from the Middle Ages

- The use of dietary changes as part of health care has ancient and medieval roots

I hoped the students enjoyed our short detour into an odd corner of the medieval world.

Blessings,

Dave