Today there is much talk surrounding the idea of the lack of communal identification in America. We have red states, and blue states, and we bowl alone. Our kids don’t go outside to play with other neighborhood kids. We have much to lament.

On the other hand, this social/cultural shift (for our purposes here we’ll assume it’s true) has given us some distance from the whole concept of a “nation.” Paul Graham has a marvelous post entitled “The Re-fragmentation” in which he discusses the darker side of everyone huddled together around the center. One could argue that the prime era of nationalism produced an eerie cultural conformity on a scale perhaps not seen since ancient times.

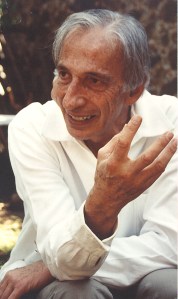

It is this spirit that Benedict Anderson writes Imagined Communities. The book attempts to tackle how it is that communities called “nations” formed. At times I thought he drifted into a bit of esotericism, but I found other insights of his incisive and quite helpful. The first of these insights is in the title itself. Nations require imagination. We can understand that those within an immediate geographic proximity could be a community. We can surmise that those of like-minded belief could find a way to become a community. But how might I be connected with someone in Oregon with whom I may not share either belief, geography, experience, or culture? It requires a certain leap of the imagination.

called “nations” formed. At times I thought he drifted into a bit of esotericism, but I found other insights of his incisive and quite helpful. The first of these insights is in the title itself. Nations require imagination. We can understand that those within an immediate geographic proximity could be a community. We can surmise that those of like-minded belief could find a way to become a community. But how might I be connected with someone in Oregon with whom I may not share either belief, geography, experience, or culture? It requires a certain leap of the imagination.

Anderson cites two texts from the fathers of Filipino nationalism to demonstrate how this idea of a national community could be formed. The first is from Jose Rizal:

Towards the end of October, Don Santiago de los Santos, popularly known as Capitan Tiago, was giving a dinner party. Although, contrary to his usual practice, he announced it only that afternoon, it was already the subject of every conversation in Binondo, in other quarters of the city, and even in the city of Intramuros. In those days Capitan Tiago had the reputation of a lavish host. It was known that his house, like his country, closed his doors to nothing — except to commerce or any new or daring idea.

So the news coursed like an electric shock through the community of parasites, spongers, and gatecrashers, whom God, in His infinite goodness, created, and so tenderly multiplies in Manila. Some hunted polish for their boots, others looked for collar buttons and cravats. But one and all were occupied with the problem of how to greet their host with the familiarity required to create the appearance of long-standing friendship, or if need be, to excuse themselves for not having arrived earlier .

The dinner was being given on a house on Anloague Street. Since we cannot recall the street number, we shall describe it such a way that it may be recognized — that is, if earthquakes have not yet destroyed it. We do not believe that its owner will have had it torn down, since such work is usually left to God or Nature, which besides, holds many contracts with our Government.

The second from Marko Kartikromo

It was 7 o’clock Saturday evening; young people in Semarang never at home Saturday night. On this night, however, no one was about. Because the heavy day-long rain had made the roads wet and very slippery, all had stayed at home.

For the workers in shops and offices Saturday morning was a time of anticipation–anticipating their leisure and the fun of walking around the city in the evening, but on this night they were to be disappointed–because of the lethargy created by the bad weather. The main roads usually crammed with all sorts of traffic, the footpaths usually teeming with people, all were deserted. Now and then the crack of horse cab’s whip could be heard spurring a horse on its way.

Samerang was deserted. The light from the gas lamps shone on the shining asphalt road.

A young man was seated on a long rattan lounge reading a newspaper. He was totally engrossed. His occasional anger and smiles showed his deep interest in the stories. He turned the pages of the newspaper, thinking that he might find something to make him feel less miserable. Suddenly he came upon an article entitled:

PROSPERITY

A destitute vagrant became ill on the side of the road and died of exposure

The report moved the young man. He could just conjure up the the suffering of the poor soul as he lay dying on the side of the road. One moment he felt an explosive anger well-up inside. Another moment he felt pity, and yet again he felt anger at the social system which made some men poor and others rich.

If we contrast these texts with two other famous opening passages (The Iliad, and Pride and Prejudice) we may begin to see why the above texts could be described as “nationalistic.”

Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another.

And which of the gods was it that set them on to quarrel? It was the son of Jove and Leto; for he was angry with the king and sent a pestilence upon the host to plague the people, because the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses his priest. Now Chryses had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom: moreover he bore in his hand the sceptre of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs.

“Sons of Atreus,” he cried, “and all other Achaeans, may the gods who dwell in Olympus grant you to sack the city of Priam, and to reach your homes in safety; but free my daughter, and accept a ransom for her, in reverence to Apollo, son of Jove.”

On this the rest of the Achaeans with one voice were for respecting the priest and taking the ransom that he offered; but not so Agamemnon, who spoke fiercely to him and sent him roughly away. “Old man,” said he, “let me not find you tarrying about our ships, nor yet coming hereafter. Your sceptre of the god and your wreath shall profit you nothing. I will not free her. She shall grow old in my house at Argos far from her own home, busying herself with her loom and visiting my couch; so go, and do not provoke me or it shall be the worse for you.”

The old man feared him and obeyed. Not a word he spoke, but went by the shore of the sounding sea and prayed apart to King Apollo whom lovely Leto had borne. “Hear me,” he cried, “O god of the silver bow, that protects Chryse and holy Cilla and rulest Tenedos with thy might, hear me oh thou of Sminthe. If I have ever decked your temple with garlands, or burned your thigh-bones in fat of bulls or goats, grant my prayer, and let your arrows avenge these my tears upon the Danaans.”

Thus did he pray, and Apollo heard his prayer. He came down furious from the summits of Olympus, with his bow and his quiver upon his shoulder, and the arrows rattled on his back with the rage that trembled within him. He sat himself down away from the ships with a face as dark as night, and his silver bow rang death as he shot his arrow in the midst of them. First he smote their mules and their hounds, but presently he aimed his shafts at the people themselves, and all day long the pyres of the dead were burning.

******

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer.

“Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

This was invitation enough.

“Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

If we consider the idea that nations are primarily imagined communities we can examine the texts.

The first two texts . . .

- Conjure up a sense of belonging to a particular place. The reader may not know the locations described in experience but can imagine being there.

- Establish a connection between the large groups of people in the story, despite the fact that these people do not know each other — note that in the second text the man feels a connection to the vagrant though they had never met.

- Presuppose an almost jocular familiarity with the the concept of a “nation.”

But neither The Illiad or Pride and Prejudice do any of these things. The reader gets dropped into a world that is not theirs, and neither author shows much concern to make it so. The reader observes the story, but does not participate in the story. If we consider Austen one of the primary literary voices of her day, we can surmise that the transition to considering “nations” as communities is quite recent. C.S. Lewis commented that the world of Austen and Homer had much more in common with each other, despite their 2500 year separation, than his world and Austen’s, despite the mere 150 year time difference.^

Too many causes exist for this momentous shift to consider them here. Anderson focuses on a couple, however, worth considering.

As mentioned above, one can have a sense of community based on physical proximity. Anderson’s brilliance is to focus on the idea of “imagination” creating this sense of community. We must always realize, then, in the essential unreality of nationhood, a subject to which we will return. But Anderson also shows the concrete foundation for the myth of nationality.

Ideologically the idea of equality had to arise before the idea of nationality had a chance. But the idea of equality needed fertile soil, and Anderson names “print-capitalism” as one primary ingredient. With the Enlightenment came the idea of rational standardization of measurement (of distance, time, weight, etc.) and language.

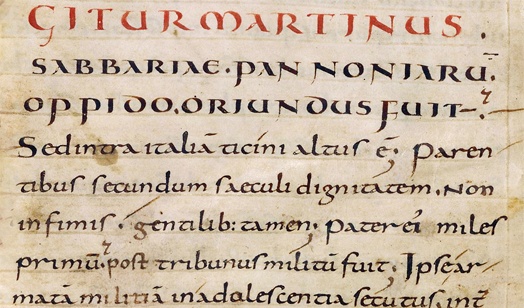

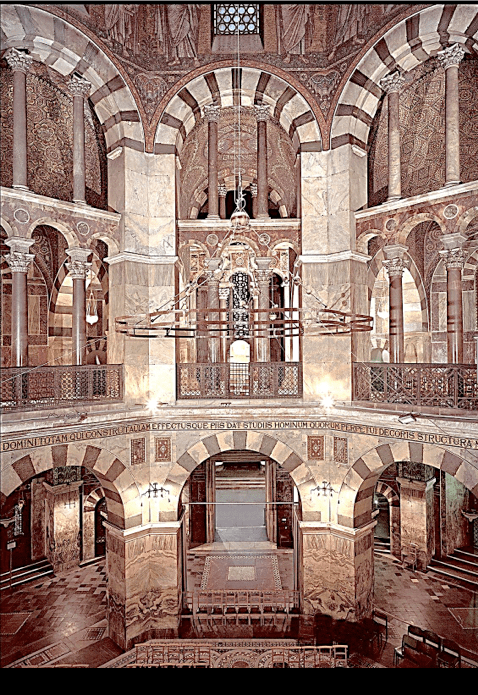

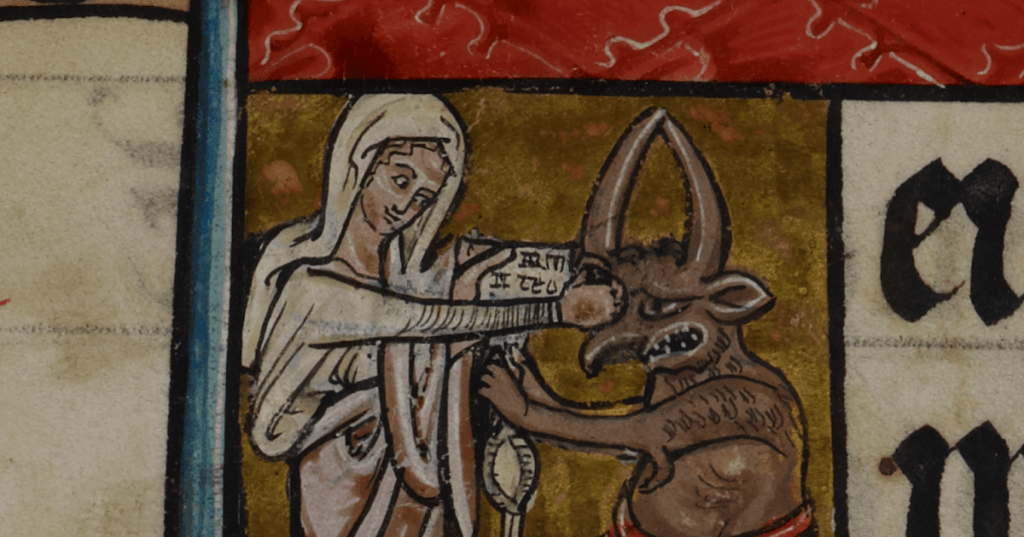

The printed book, kept a permanent form, capable of infinite reproduction, temporally and spatially. It was no longer subject to the ‘unconsciously modernizing’ habits of monastic scribes. Thus, while 12th century French differed markedly from that written by Villon in the 15th, the rate of change slowed markedly by the in the 16th. ‘By the end of the 17th century languages in Europe had generally assumed their modern forms.’

Capitalism too played its part. “In the Middle Ages,” commented Umberto Eco, “one did not ‘make money.’ You either had money or you didn’t.” Today we hear a great deal about the inequalities of capitalism. But capitalism helped produced a society in which the vast majority of people can share in common experiences though common consumption.* The mass production made possible by political unification helped create mass consumption, and so one hand washes the other. Capitalism and print media together created the newspaper, which formed the ‘daily liturgy’ of the national community.

So to what extent can we say that “nations” have value? One student of mine refused to take the bait and argued bluntly (but effectively) that “they seem to be doing pretty well so far.” Ross Douthat writes,

The nation-state is real, and (thus far) irreplaceable. Yes, the world of nations is full of arbitrary borders, invented traditions, and convenient mythologies layered atop histories of plunder and pillage. And yes, not every government or polity constitutes a nation (see Iraq, or Belgium, or half of Africa). But as guarantors of public order and personal liberty, as sources of meaning and memory and solidarity, as engines of common purpose in the service of the common good, successful nation-states offer something that few of the transnational institutions or organizations bestriding our globalized world have been able to supply. (The arguable exception of Roman Catholicism is, I fear, only arguable these days.) So amid trends that tend to weaken, balkanize or dissolve nation-states, it should not be assumed that a glorious alternative awaits us if we hurry that dissolution to its end.

I agree that the effectiveness of nations vis a vis other forms of organization is at least arguable.** I agree with Douthat that the premature burial of “nations” before their time, with nothing ready to replace it, would be silly at best. But . . . Anderson’s work reminds us that we live in purely imagined communities. They exist not in reality, but for expediency, a product of contingent historical circumstances.

The question remains — will their imaginary existence, like that of the zero, prove so valuable that they will last far into the future? We can see the challenge posed to them already by the internet, globalization, and political polarization. We shall see how strong our imaginations can be in the next generation or two.

Dave

*I do not suggest that defining ourselves through consumption is a good thing in itself, merely that consumerism has had this particular impact.

**In brief, we might say that the birth of nations was bloody (ca. 1800-1871), with the next generation settling into a relative peace. But the first half of the 20th century was catastrophically destructive, with a moderately peaceful era to follow. For whatever it’s worth, the possibly waning age of “nations” — ca. 1970’s – present, has been a period of steadily decreasing world violence.

^M.I. Finley makes an interesting connection between the two eras in his classic, The World of Odysseus. Finley looks at Achilles’ comment in Hades and draws an unexpected conclusion. Achilles seems to state that he would rather be a “thes” on earth than king in Hades. Most translations assume that “thes” means “slave,” but Finley argues that the best translation would mean something like, “unattached free small landholder.” This, and not slavery, was the worst fate Achilles could imagine.

This reminds me of a part in the Gwyenth Paltrow Emma movie where Emma disdains the independent farmer. “He has no society, no information.” We get another confirmation of the role capitalism and the concept of “equality” played in the creation of nations.