Recently I found myself talking politics with a Trump supporter. Interestingly, he mentioned very little about his policies or personality. Rather, he seemed drawn to him because of the multitude of attacks against him. No one, he argued, deserved what Trump receives from at least some in the media. Politics had very little to do with this, for this same person said that he liked both Obama and Hillary Clinton for much the same reason–in his mind of them have been attacked to an unfair extreme.

I have no great love for the Puritans, and perhaps this might explain why I sometimes seek to defend them. I certainly felt this way at the start of Richard Bushman’s From Puritan to Yankee: Character and Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765. When describing Puritan society in the first chapter he invariably uses words like, “austere,” “imposing,” “monolithic,” and that most dreaded word for an academic who originally published this book in 1967, “conformity.”*

defend them. I certainly felt this way at the start of Richard Bushman’s From Puritan to Yankee: Character and Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765. When describing Puritan society in the first chapter he invariably uses words like, “austere,” “imposing,” “monolithic,” and that most dreaded word for an academic who originally published this book in 1967, “conformity.”*

Later in the book Bushman shows his excellence as a historian of a certain type, but I did not like the first chapter.

We naturally have difficulty in understanding and evaluating the Puritans. They look like us in many respects, but then part with modern society in other radical ways. It is the heretic, rather than the unbeliever, who always poses the greater threat. Hence, our natural distaste for the Puritans. But we must keep certain things in mind.

First of all, the Puritan ideal of social order oriented around religion hardly broke new ground. They borrowed from the medieval idea of the “great chain of being,” and in orienting their society around religion they merely did what most civilizations practiced up until that point. Numerous examples of this exist, with the Egyptians, early Romans, the Mezo-American civilizations, and the aforementioned medievals to name a few (this should clue us in on the radical nature of post-Enlightenment western society–more on this later).

Secondly, many moderns, progressive or otherwise, would likely admire some of the main goals of Puritan society. The Puritans sought to live a common life together by minimizing (though not eliminating) economic competition and distinctions in wealth. Bushman himself notes that in the early days of settlement even the richer members of society lived much in the same way as their neighbors, working fields and milking cows like anyone else. Bushman and others may not realize that such a society cannot exist with modern notions of liberty that tell us to “find our own way,” “follow your heart,” and so on. Societies like the early Puritans must get their formation from shared conviction that only comes with religious belief. You cannot have one without the other. One Puritan stated, “Law should serve free exercise of just privileges. Without this, lives and liberties would be a prey to the covetous and cruel.” Modern notions of liberty, in the view of early Puritans, would lead to exploitation and alienation.

Bushman himself cites early in chapter two that this shared communal life allowed government in Connecticut to be, in his words, “flexible” in ways that “minimized local conflicts.” This hardly seems “austere,” or “monolithic.”

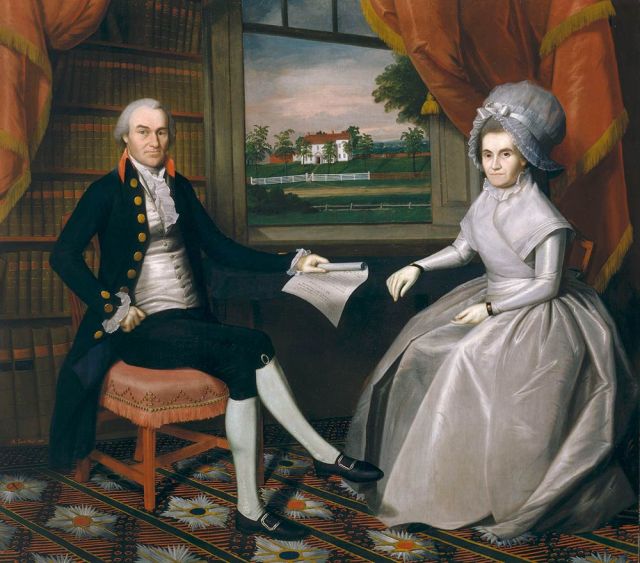

True, certain “upper-crust” Puritans (apologies for the emotionally laden word choice) had a fear of any of the “lesser sort” getting into political power. We can snub our noses at this. But we should remember that it is 1700. Puritan Connecticut was more democratic than the England of William and Mary, and infinitely more so than Louis XIV France or Frederick the Great’s Prussia. Almost every other European society at the time shared these same fears of “lesser men” ruining everything. We have good evidence that many of our founders decades later had these same fears, as of course did every major western political thinker from Homer on down the line.

Finally, nearly all the early Puritan settlers came from the same east-Anglia towns and villages. They knew the content of Puritan theology, they knew Puritan leadership. It’s not as if the Puritans pulled a bait-and-switch on the journey across the Atlantic–“You thought you signed up to run wild and free in the woods, but no! Now that we have you in the middle of the ocean, welcome to John Calvin!”

If some settlers grew frustrated with Puritan leadership, well, they knew what to expect.

So yes, the Puritans need criticism, but criticism with the right context in mind, and aimed in the right place.

After chapter one, Bushman shows his great skill at sifting through data to form larger conclusions. He puts the focus on the problems settlers faced due to a growing population, which would necessitate an inevitable territorial expansion of the colony. Some civilizations, like the Romans, link most everything in life to land. Some see the beginning of the Roman Republic’s political problems beginning the moment land in Italy disappeared for their soldiers.** Not every civilization operates with this mentality. Carthage, for example, and possibly Periclean Athens, largely freed themselves from land as a measure of identity (they had different problems). But our early settlers fit well within the Roman mindset.

In the first generation or two land distribution remained equitable. The size of the colony allowed everyone to attend the most important churches pastored by the acknowledged town leaders in piety and purpose. The population’s proximity to these churches and to town hall bound the colony together politically.

But time marches on, and fathers want the same for their younger sons as for the oldest. In a settled mostly aristocratic society like England of the time, the younger sons of even minor aristocracy join the army or perhaps the clergy. You see this even in Austen’s novels 100 years later. Settlers in the new world, however, believed in equality, more or less, and wanted everyone to have an equal chance.

Expanding the size of the colony meant greater distances from the town center. Naturally those predisposed to want to lead the settlement would stay close to its center. Those with some disaffection towards leadership might more easily head a few miles outbound. With this even small scale migration came an inevitable tension, and an inevitable choice.

The colony could either, a) Split off in different settlements and grant autonomy to each. However, this came with the problem of effectively ending the Puritan dream. Those who left for outbound land tended towards a more enterprising, individualistic mindset. Or they could, b) Increase the power of the original settlement’s leaders and weaken the participatory democracy carefully crafted by the original settlers.

As is typical of most any democratically government they chose neither absolutely, though probably favored option ‘b.’ Everyone recognized that the social order had suffered due to increased wealth–a wealth occasioned by expansion (again, similar to Rome ca. 200-75 B.C.). But try as they might, too many things swirled in conflict with one another to make sense of it all. In the end tensions increased between eastern and western settlers in most religious and economic matters. Once they let the’Yankee’ mentality of individual enterprise get its foot in the door, their social construct had its days numbered.

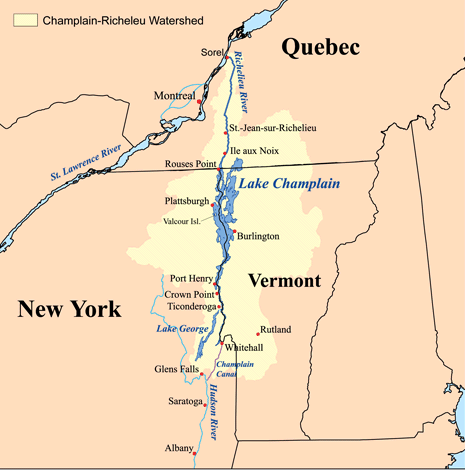

Let us give credit where due. Bushman’s work should help us to see certain larger issues with more clarity. For example, Thomas Jefferson bucked historical convention in his belief that a republic should have lots rather than a little territory. He hoped that the Louisiana Purchase would allow everyone to practice self-government and live free and independently on their own land. But–if everyone can live free and independently from one another, how can we maintain order? Only by doing as the Puritans attempted to do–by increasing executive authority. If we want the kind of liberty envisioned by Jefferson, let us count the cost. Rome saw this same increase of executive authority as their territory expanded beyond Italy. Whatever our uniqueness as a nation, we cannot escape history.

But in the end I think Bushman misses the real point.

Bushman mentions religious issues and gives them due treatment, but he gives pride of place to the decline of Puritanism to land and economic issues. He deals with the source material masterfully. But he seems to argue that certain geographic and social issues caused the religious issues to manifest themselves later. We can acknowledge the influence of geographic and economic factors. But in the end, I think he puts the cart before the horse. The key to Puritan disintegration must be found in their religion.

For example . . . the Roman Republic experienced some of the same stresses faced by the CT settlers, with a much larger population over much larger territory. Yet, the Republic maintained its central identity for at least two and perhaps three and half centuries, in contrast to Puritan ideals lasting no more than two generations. Egyptian civilization also had some of the same issues regarding land, and though obviously not a republic, maintained their identity for perhaps 1500 years.

Yes, democracies traditionally have a problem maintaining identity and cohesion. One can a make a good case that Pericles built the Parthenon primarily as a way to reestablish unity by calling people back to their religious roots, whereas we today tend to look at this period in Athens as the pinnacle of democratic experience. This “pinnacle of democratic experience” may have had more cracks than we initially assume. Athens at this time certainly had lots of money, which tends to work ill upon democracies. If Thucydides tells only mostly the truth, they did not have much social cohesion. Rome lasted longer than CT or Athens with similar geographic and economic factors at play, and so I feel a reason exists beyond land distribution and the expansion of trade that Bushman focuses on.^

In the Puritans particular case we should note that their theology departed from traditional orthodox Christianity in certain respects. Their emphasis on the will of God rather than the love of God reduced their faith to more of a philosophy, a handbook of propositions for life.^^ They had no appreciation for sacraments and thus no way for the grace of God to be made manifest in their lives except by how they thought. This led to impersonal abstractions gaining sway. The famous (or infamous if you prefer) 5 Points of Calvinism work on the mind like a geometric proof, inexorably moving toward a foreordained conclusion. Abstract ideas, however, are slippery things, and ideas floating in the air don’t always land on the ground in the same form for repeated generations. Like a point in infinite space, various lines can connect with it and go almost anywhere.

Interestingly, Puritans created a government structure that tended toward defending an abstract notion of rights. As the colony expanded, Bushman documents a swell of lawsuits and disputes centered around the “claims” of one settler vs. another. Communal relationships disappeared as “rights” dominated public discourse. Religious revivals like the Great Awakening followed this pattern in some ways.. The religious impulse coming from this revival did not push people back into communal life. Rather, we see a rise in the individualistic idea of the “liberty of the conscience” gaining the upper hand among the (formerly) Puritan settlers.

Whatever the merits of my very incomplete analysis above, by the early 19th century New England certainly had adopted a vague mixture of theism and deism as its unofficial religion–a death by abstraction.

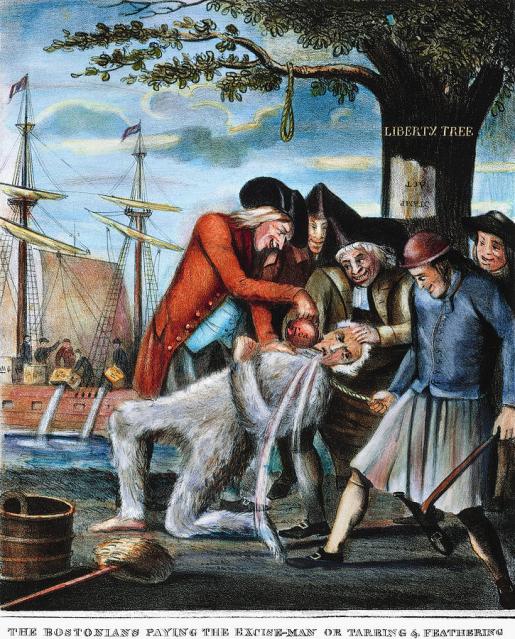

We see hints of 1776 as this abstract notion of rights grew. In time colonial corporations made grants of land to settlers. When royal officials came over and examined these title deeds they annulled them outright. No “corporation,” they argued, can grant title to anything. What is a “corporation” after all? It’s surpra-personal identity meant it had in effect no personality, and with no personality, how could it truly exist? A king can grant title, for the king is an actual person, and actual people can own things and give them to others.

The colonists may have nodded “sure!” to these royal representatives, but likely crossed their fingers behind their backs. Though kingship has the advantage of being personal, a king across an ocean has perhaps even less personality than a corporation. In any case, they no longer had a connection to government rooted directly in either religious belief or social ties. They put their eggs in propositions, in “rights,” in “liberty of conscience,” which no one can touch. Their point in infinite space must be free to go where it pleases.

A standard debate among historians of the American Revolution involves the question of whether or not the founders were radical or conservative in their ideas. Years ago I would have answered with the latter, but not anymore. Bushman’s work accompanies Bernard Bailyn’s and Gordon Wood’s thesis that our stodgy, wig-wearing founders had radical ideas. For the first time, society would not be oriented around God/the gods. Nor would social order have its roots in personal relationships, i.e., feudal society, or the lives and patronage of prominent families. Now for the basically the first time, society would be organized around certain ideas, or we might almost say, geometric axioms. What Bushman’s book shows us is that you don’t need to go to 1776 to see these principles at work. If you wish, you can content yourself with a small CT settlement, ca. 1700.

*******************

*Here I must give credit to the playwright Arthur Miller. His work The Crucible certainly criticized certain aspects of Puritan society. And yet in his preface to the play he spends most of his time trying to get the reader to sympathize with the Puritans. This sympathy, in fact, serves as the only solid basis for critique.

**I think the land issue a contributing factor accompanying deeper causes for Rome’s Republic, much in the same way I think Bushman overstates land issues as the primary cause for the collapse of the Puritan ideal. In Rome’s case, one can see a shift in religious belief occasioned by their contact with Greece and the Mediterranean as the precursor to their political and social fragmentation.

^This is another great example of how Bushman’s book shed’s light on larger issues. Most every commentator on Plato’ Laws calls Plato a grumpy old fart for banning trade from his theoretical realm. But increased trade undeniably negatively impacted CT’s social order. Farmers deal roughly with the same soil and the same weather. Surplus food grown by one poses no real threat to other farmers.

But trade seems to encourage more of the competitive spirit. Trade deals more with luxuries than necessities, so unsold surpluses can ruin a merchant. Hence, the extra competition to sell, and so on. The rise of money and trade certainly played a role in the demise of Rome’s Republic.

^^I realize that this one sentence is hardly a reasonable defense for my views on Puritan theology, My apologies–to defend them here is a bridge too far for me. If I am correct, however, there are some similarities in Puritanism to Stoicism (I stress “some”–the Puritans probably gave much more room for the emotions than the Stoics), a religion for Greece and Rome’s intellectual elite, but not for the masses.

Royalty has always sought to maintain this distance through their dress, their manners, their homes, and so on.

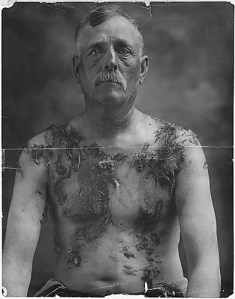

Royalty has always sought to maintain this distance through their dress, their manners, their homes, and so on. butchering most of those inside. The death of Marie Antoinette’ friend Princess Lamballe exemplifies France’s descent into paganism. They cut off her head and paraded it in front of Marie’s prison window. Then, according some accounts, they also cut out her heart and ate it.

butchering most of those inside. The death of Marie Antoinette’ friend Princess Lamballe exemplifies France’s descent into paganism. They cut off her head and paraded it in front of Marie’s prison window. Then, according some accounts, they also cut out her heart and ate it.