Those who regularly read this blog know that I tend to favor traditional values and traditional societies. Those like me need to realize that things change inevitably, making the challenge knowing how to change and stay the same all at once. Those on the opposite side need to realize that “change” is not a good word, any more than “tradition” is a dirty one.

Traditionalists must face the question of the role of technology. Certainly one could have a society that held tightly to tradition with little-no technological development. Is it possible for tradition to captain the ship while innovating technologically, and maintaining a robust economy? The question has immediate cultural and political relevance for those like me, Charles Haywood, and others. Much of our economic growth appears dependent on new technology. If a new cultural and political version of America is on the horizon, can it combine an anchor of tradition and still give us Amazon (which I do not regard as a dirty word necessarily)? Or, perhaps we need to choose one or the other, and accept the consequences. I have no clarity on this, though I suspect we may have to choose.

This question has interest in the abstract, but possibly we gain more clarity if we have a specific example, maybe even one out of left field . . . such as the development of handwriting from the classical era until today.

Ancient Writing and its Influence by B.L. Ullman lives up to its title but in a narrow sense. Ullman wrote originally in 1932–thankfully. I think if he wrote today it would be impossibly technical with much poorer writing. Even so, many parts of the book I read with semi or fully glazed eyes. As a sample, I open randomly to page 74, which reads,

The term half-uncial is sometimes used for mixed uncials of the type described, but in a narrower sense it applied to a very definite script that became a rival of uncial as a book script from the fifth to eight centuries. Again the name is unfortunate in its suggestion that it was derived from uncial. Rather it is the younger brother of that script, making us of an almost complete minuscule alphabet. It does not use the shapes of ‘a’, ‘d’, ‘e’, ‘m’ characteristic of uncial script but rather those of modern minuscule type, except that the ‘a’ is in the form used in italics, not roman. The only letter which maintains its capital form is ‘N’, and this letter readily enables one to distinguish this script from later minuscule. The reason for the preservation of this kind of ‘N’ was to avoid confusion with the minuscule ‘r,’ which in some half-uncials is very much like ‘n.’ The desire to avoid ambiguity is seen also in the ‘b,’ which is the form familiar to . . .

So, what Ullman means mostly about influence is how one form of writing influenced another kind of writing in a nearly purely technical sense. I wanted more on how changes in writing either propelled or reflected changes in the culture at large. Ullman gives us some hints of this, and his extensive, precise knowledge gives some space to the reader for guessing on our own.

We can start by recognizing that the phonetic alphabet itself ranks as one of the more propulsive and destructive (creatively or otherwise) of human technologies. Marshall McCluhan noted this with keen historical insight, in a famous interview (the ‘M’ is McCluhan, the ‘Q’ for the interviewer):

M: Oral cultures act and react simultaneously, whereas the capacity to act without reacting, without involvement, is the special gift of literate man. Another basic characteristic of [pre-modern] man is that he lived in a world of acoustic space, which gave him a radically different concept of space-time relationships.

Q: Was phonetic literacy alone responsible for this shift in values from tribal ‘involvement’ to civilized detachment?

As knowledge is extended in alphabetic form, it is localized and fragmented into specialities, creating divisions of function, classes, nations. The rich interplay of the senses is sacrificed.

Q: But aren’t their corresponding gains in insight to compensate for the loss of tribal values?

M: Literacy . . . creates people who are less complex and diverse. . . . But he is also given a tremendous advantage over non-literate man, who is hamstrung by cultural pluralism–values that make the African as easy a prey for the European colonialist as the barbarian was for the Greeks and Romans. Only alphabetic cultures ever succeeded in mastering connected linear sequences as a means of social organization.

Q: Isn’t the thrust of your argument then, that the introduction of the phonetic alphabet was not progress, but a psychic and social disaster?

M: It was both. . . . the old Greek myth has Cadmus, who brought the alphabet to man, sowing dragon’s teeth that sprang up from the earth as armed men.

My meager knowledge of pre-historic man (so called) will not prevent me from thinking that McCluhan exaggerates to a degree–the written word need not totalize all of our being. Still, we must acknowledge that we cannot expand our abilities infinitely, and if we go “deep” in one area we will certainly see shallow waters in other aspects of our being. We can also acknowledge that we how we present the world to others will reflect and shape our beliefs about the world. It need not be the chicken or the egg as to whether it reflects or shapes–we can say that both happen.

Ullman makes a few opening technical remarks perhaps designed to quell those who want to make large conclusions from changes in writing over the years. Sometimes changes in writing come from changes in the medium of the writing. Writing primarily on stone lends itself much more to straight lines and hard angles, as opposed to paper or even papyrus. Very true, but this also begs the question as to why a people use stone or scrolls in the first place. Eventually certain choices become second nature, but not at the beginning of the switch, which involves more conscious choice. I remain convinced that switches in the medium for writing, and how they write, surely mean something. Few aspects of our being rank higher in importance in our desire to connect with others, to achieve understanding from person-person, not just of content but of the meaning of that content. We accomplish this best face-to-face, where we express the full panoply of the message with our bodies as well as words. This means that when apart, the written words we choose, and how we present those words, seek in some way to make up for the absence of the body.

For this reason, and others, I say we can deduce much from the script of a civilization.

My theory runs like so: the more a civilization develops, the more refined its writing. This, I admit, means hardly saying anything more important than 2+2=4. But I hope to venture a step further, and suggest that perhaps we can wonder whether that development/refinement will still allow a people to preserve its civilizational ethos, or propel it away from its center. Not all growth is good.

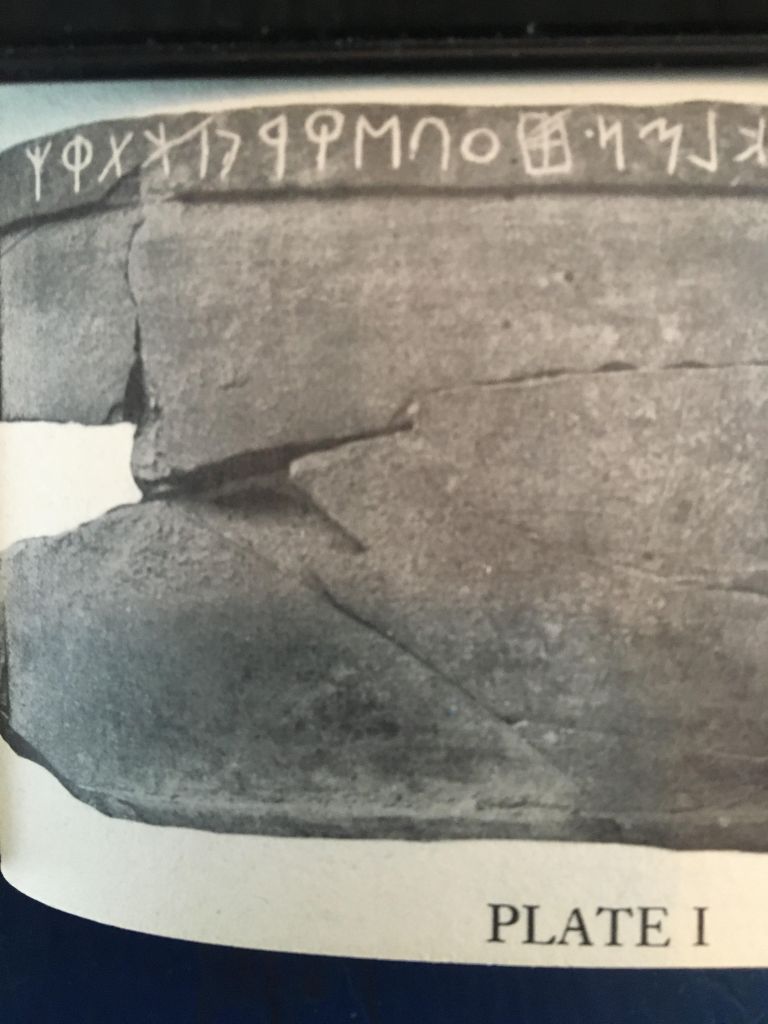

We can start by examining the development of Roman script, with the first example from perhaps the 6th century B.C.

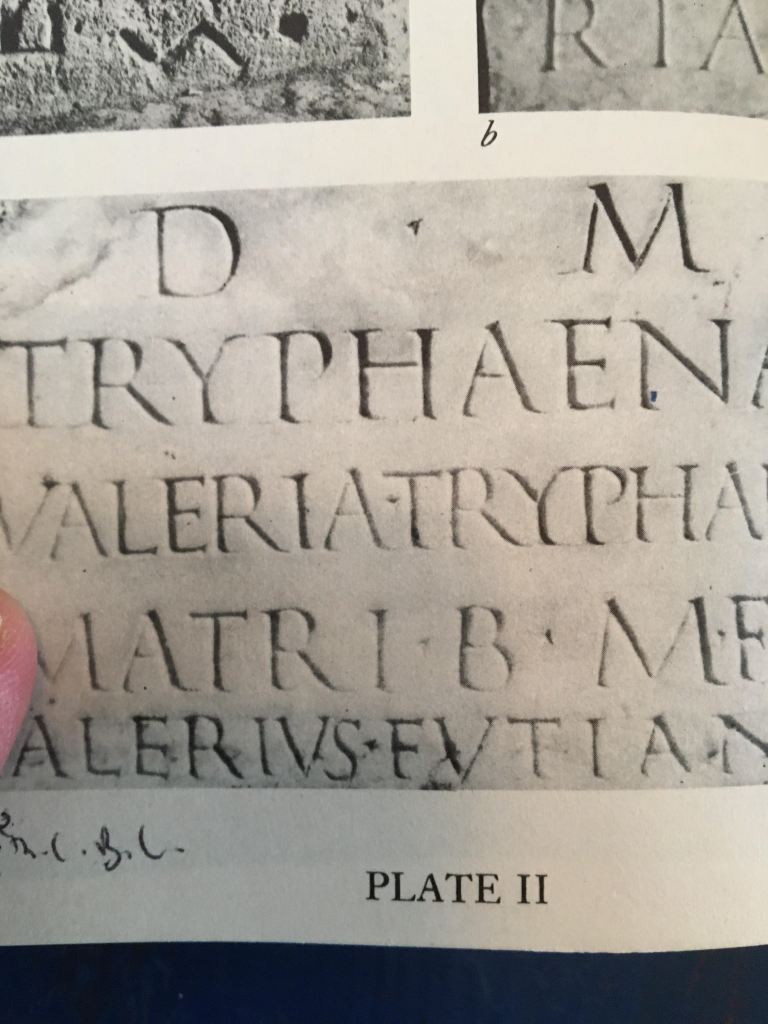

And now, moving forward in time to ca. AD 70

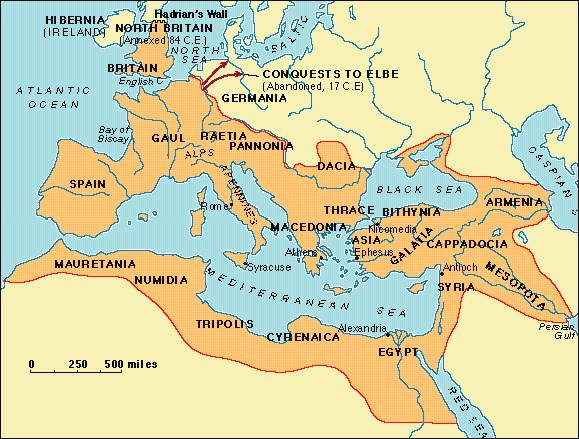

The latter examples show refinement and a development into a clear style that everyone recognizes as “Roman.” But with the codification has come “Empire.”

As the empire declined and we move into late antiquity, their writing changed as well, showing perhaps more of a Greek influence, with these first examples from likely the 400’s AD (apologies for intrusion of my fingers).

and these from 1-2 centuries later.

I suggest the changes could come from from more cultural blending, and less control over the empire, as the differences between barbarian and Roman blurred.

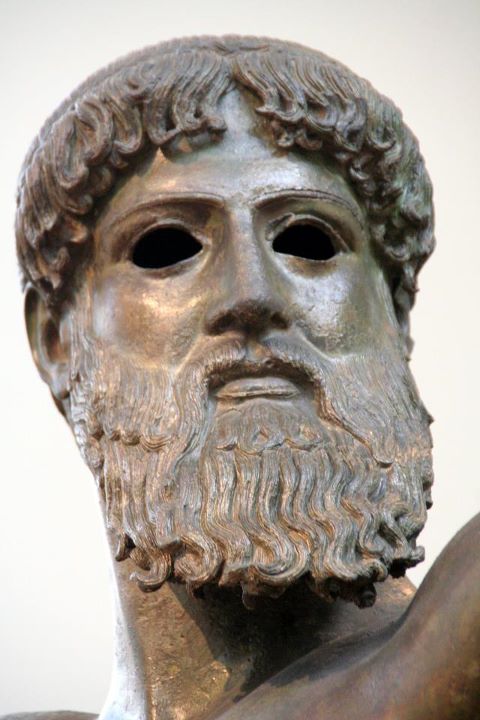

And now, for the development of Greek script. First, from 700 B.C.

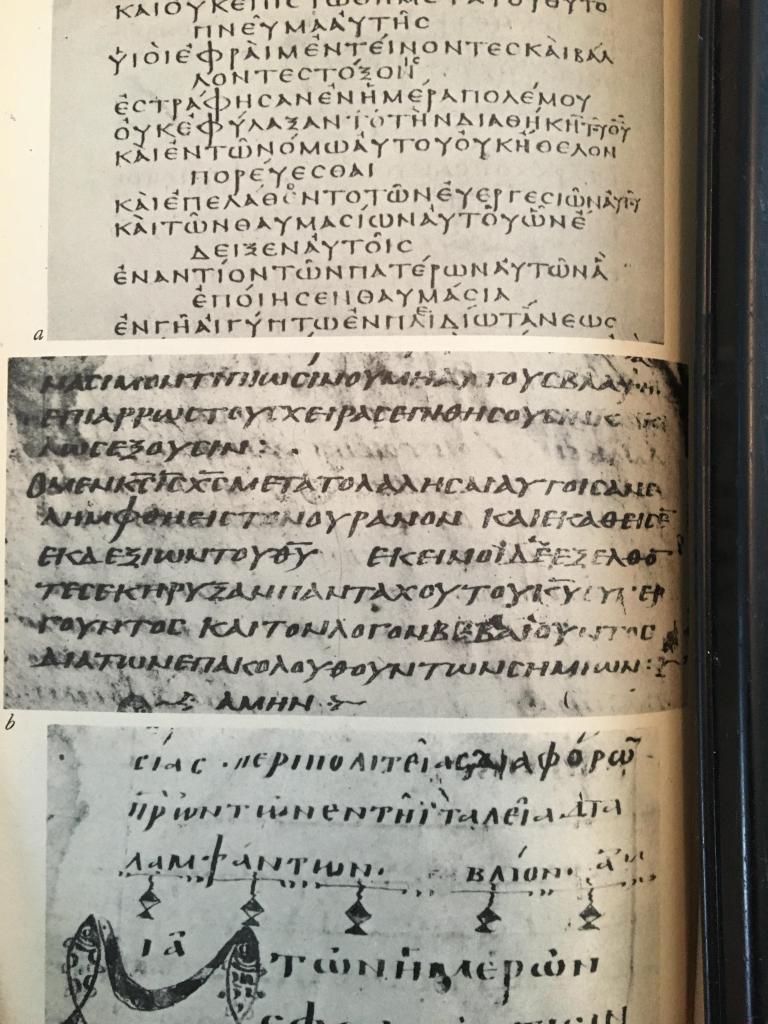

Within just a few centuries, we see quick development of a more elegant but also more “rigid” script style, from the 5th century BC in Athens, with the second example a few decades later than the first.

As Greek power wanes in the 4th century BC, their script becomes a bit more fluid, just as in Rome:

With the establishment of more Roman presence in the Greek east after Constantine, Greek script grows a bit more fluid over time, with the examples below showing a progression of about a century.

Then, as the western part of the empire collapses, the writing gets more fluid and stylized, with the dating as the 9th century, 12th century, and the 15th century, respectively, just before Moslem conquest of Constantinople.

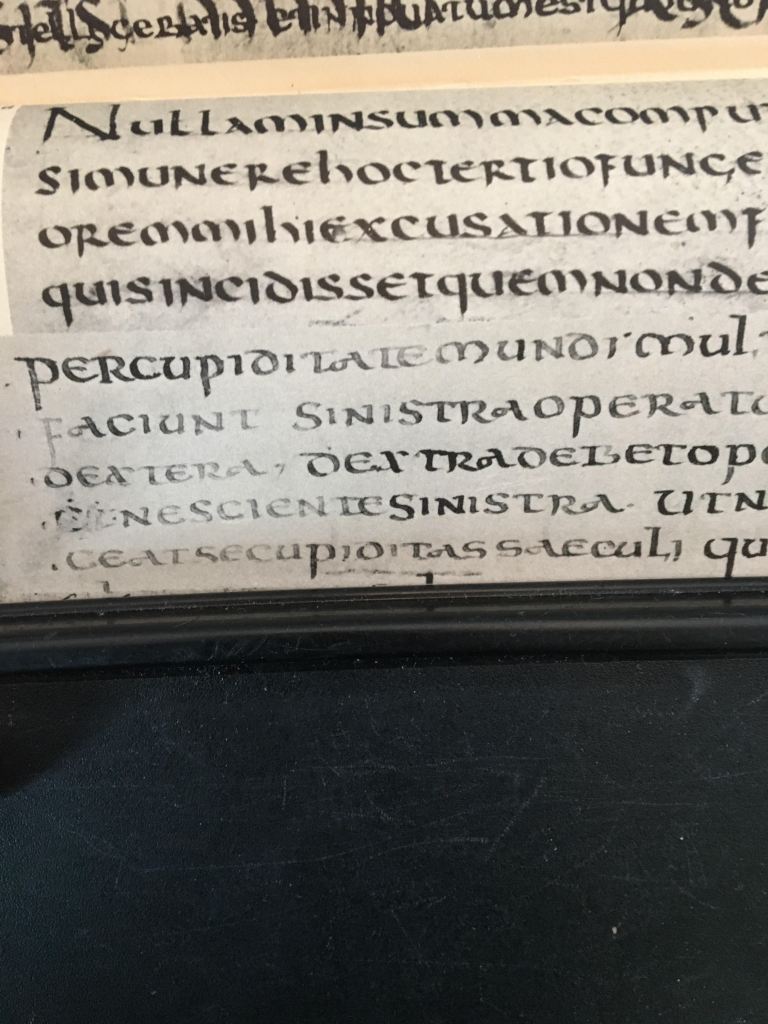

In the west, the collapse of Rome led to the development of a new civilization. First, for some context, Roman writing in the 5th/6th centuries, AD:

and Visigothic writing from north Italy, ca. 9th century AD:

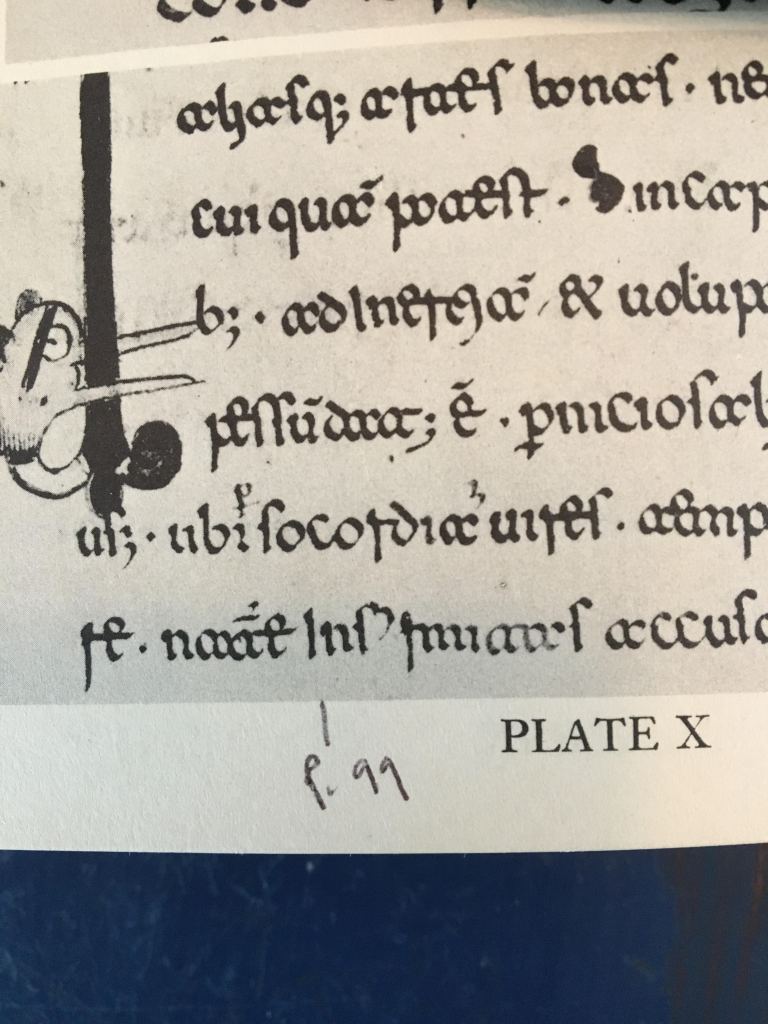

Other European cultures had a bit more development than the Visigoths, however, and we see this reflected somewhat in their script, with the first two being Anglo-Saxon from the 8th century, and the last Carolingian from the 9th century, as the “Carolingian Renaissance” had gotten underway by then:

By the 12th century, we see more elegance and uniformity, as in previous civilizations over time.

In parts of France, we have a parallel development of sorts, with each example progressing from the early to late 9th century near Tours.

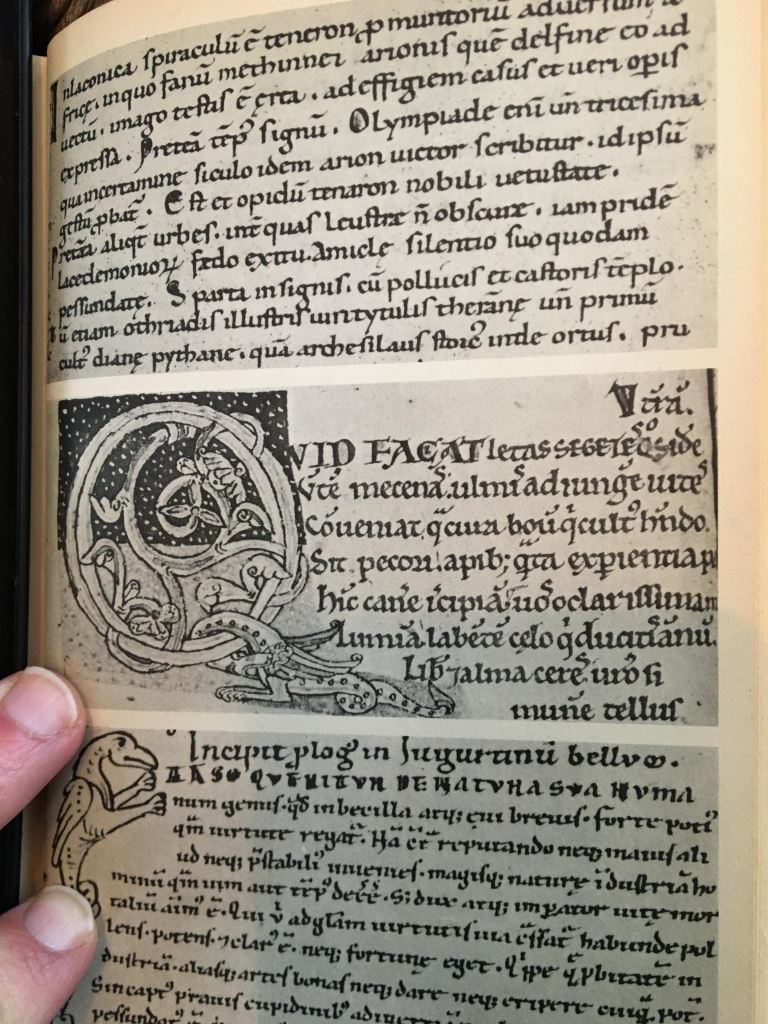

As the Middle Ages develop, you get more refinement, but less overall readability, with these examples from the 12th century,

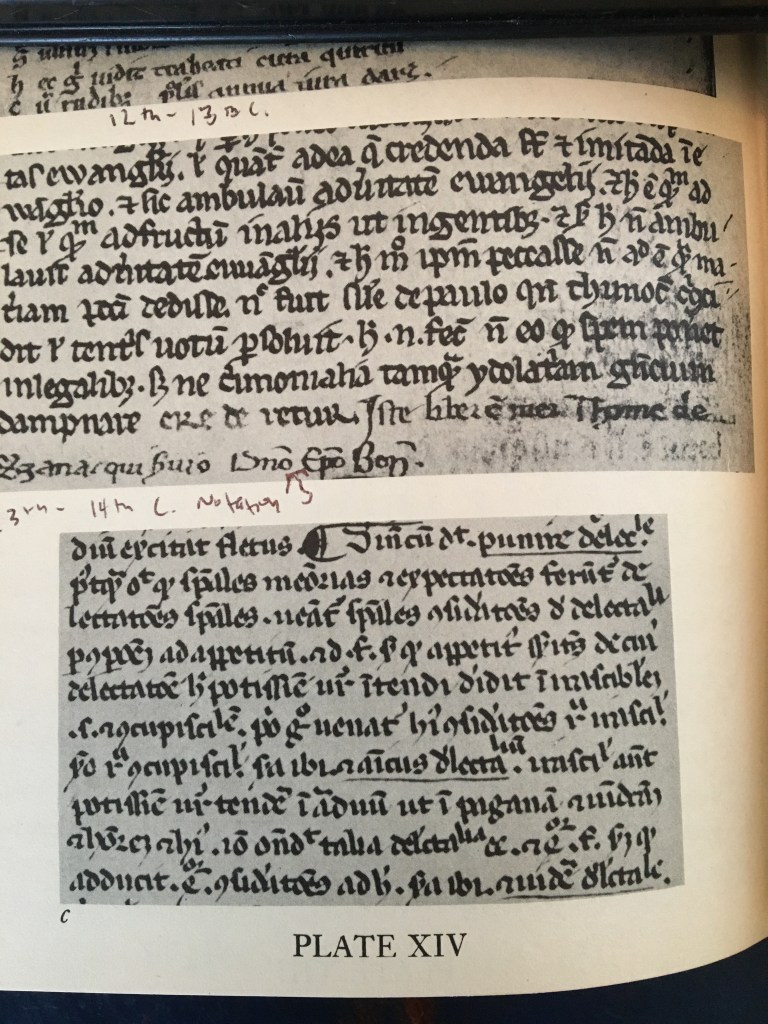

and then into the 13th and 14th centuries,

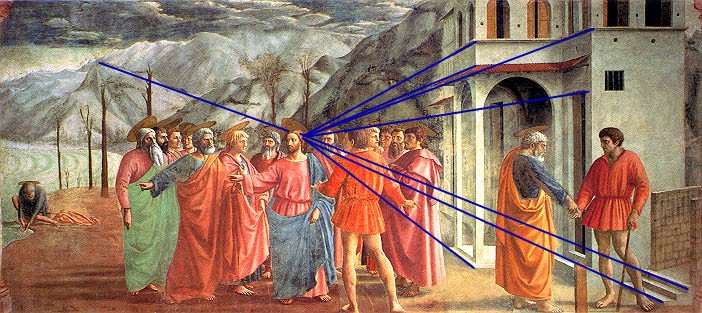

which seems to almost beg for a correction with the coming of the Italian Renaissance in the mid-15th century.

Ullman’s excellent visuals make his text intelligible for novice’s like myself, and allow us to speculate on some broader conclusions.

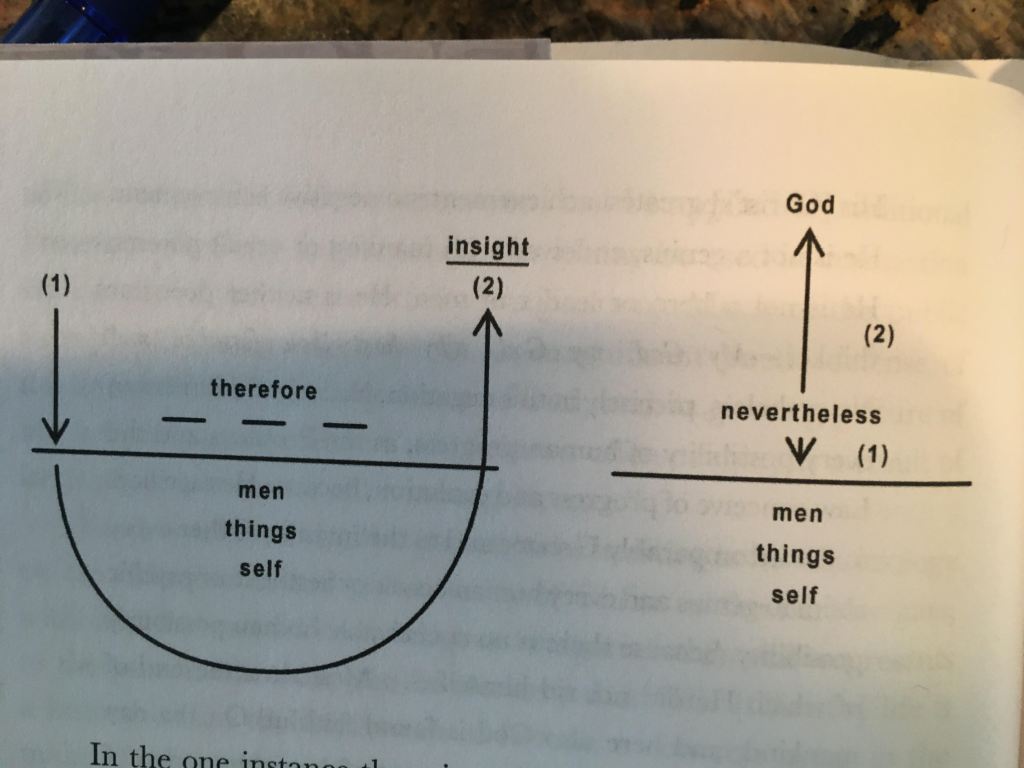

It seems that the scripts go through three phases that seem to circle back on one another.

- First, you have early script, which has less uniformity, is “sloppier,” and more free, in a way.

- Second, as the civilization develops and gets on its feet and flexes a bit, the script gets more uniform, and certainly in the case of Greece and Rome, “blockier.”

- Then, as the civilization wanes, either physically, intellectually, or both, the script gets more fluid. In Rome, you see the blending of Greek and Roman influences towards late antiquity. In the Middle Ages, you see ornamentation increase nearly beyond the pale, which brings back the more Roman/Carolingian, unified style.

One might suggest that we get a an interesting comparison between the Roman Empire of the Augustan age, the Byzantines, and the Latin west at the “peak” of their powers. Roman script screams empire and control (see “Plate 2” above), whereas the other two have more breath in their writing, with more feminine qualities. I think the comparison helps, but we must take the scholar’s caution, for Ullman reminds us that writing on parchment allows for a lot more fluid motion than writing on stone.

We can apply all of this to our original question: can a civilization maintain a firm anchor in tradition and still innovate?

As Rome’s republic fell into disarray, many contemporary historians lamented the decline of the old ways. Historians always lament the decline of the old ways. But Rome’s unwritten constitution relied on tradition to work, and the letter of the law could not save the republic. We know too that Augustus sought to promote a return of traditional values even as he consolidated power in a non-traditional way, an indication that the contemporary perception that “times had changed” involved more than “grumpy old man” Roman historians like Livy and Polybius. We can confidently say that Rome gives us significant data point that points to tradition eroding as innovation in their writing increased.

Greece has a slightly different story. They standardize their writing more quickly than Rome, and then change it a bit more quickly again after that. Their more fluid and script has a warmer, more human feel, and suggests that perhaps they maintained traditions more effectively than Rome (and perhaps also their proximity to water). However, no one argues that Greece in the 4th-3rd centuries BC were at the top of their game.

As for the Byzantines, a variety of historians from the Enlightenment onwards critiqued what they saw as their slippery, devious methodology in international relations. Edward Luttwak’s brilliant book on the Byzantine’s grand strategy shows that their foreign policy choices were methodical and moral, consistent with a power facing multiple enemies over a wide front. Surprisingly or no, their handwriting seems to mimic the fluidity of their geopolitics. My knowledge of Byzantine history has gaping holes, but based on my perusal of The Glory of Byzantium they maintained a clear and consistent artistic style while innovating and changing their technique. Marcus Plested has shown that many theologians interacted positively with the early medieval philosophical tradition. They seemed to manage a balance of some kinds of innovation without sacrificing tradition and identity. However, they fell to the Moslems, albeit after a 1000 year run. If innovation forms the kernel of success and power (a big “if), they failed to innovate fast enough to protect themselves fully.

With the medievals we see something similar. They created an original style that peaked perhaps in the 11th-12th century, the same century that saw an explosion of cathedral construction in the Gothic style. In both writing and architecture, one sees innovation that reinforced rather than altered their traditions. But Ullman argues–and the visual evidence seems indisputable–that as their script continued to “innovate” its actual functionality markedly decreased. They then snapped back to the tradition of writing extant centuries prior. But the Renaissance had no intention of reaffirming tradition per se. Instead, Renaissance humanists led an artistic, architectural, and philosophic movement that dramatically changed society, abandoning a host of medieval traditions (though in fairness the Black Death had a lot to do with this as well).

Our look at four civilizations fails to provide a decisive answer. In Rome and classical Greece, innovation seemed to stifle tradition and presaged decline. In Byzantium and medieval Europe, innovation initially accompanied “measurable” growth in their civilizations, to say nothing of what we cannot measure, but it seemed also to run its course. Nothing lasts forever, and one wonders whether or not civilizations can possibly extend their lives ad infinitum regardless of their choices to rapidly change or resist it at all costs.

It seems we must table the discussion, but we have hints. We don’t often think of tradition and fluidity existing in tandem, but it works at least when both sides get the balance right. After all, men and women have been marrying each other since the dawn of time. Perhaps what we see in Gothic Europe and Byzantium should not therefore surprise us. Perhaps the desire to lock things in place too severely effectively takes the air out of tradition, killing the best of what makes a civilization tick, i.e., Athens killed Socrates just as they rigidified their script. Perhaps we can conclude these things if handwriting reliably guides us.

Dave