You will notice some dated references, as this post was originally written in the fall of 2020. The original is below . . .

****************************

I enjoy athletics, but since the lockdown last March I have watched zero hours of live sports. One might think that televised sports would act as a lifeline for people like me during these strained times, but my interest has markedly declined. But it’s not just me, apparently. Ratings have plummeted for live sports across the board. Here are some statistics:

- US Open (golf) final round: down 56%

- US Open (tennis) was down 45% and the French open is down 57%

- Kentucky Derby: down 43%

- Indy 500: down 32%

- Through four weeks, NFL viewership is down approximately 10%

- NHL Playoffs were down 39% (Pre Stanley Cup playoffs was down 28% while the Stanley Cup was down 61%).

- NBA finals are down 45% (so far). Conference finals were down 35%, while the first round was 27% down. To match the viewership, activity on the NBA reddit fan community is also down 50% from the NBA finals last year.

So it’s not just the woke politics in some of our major sports that are driving people away. The above statistics are from blogger Daniel Frank. He suggests a variety of reasons for this decline, including the rise in mental health issues and political uncertainties that eliminate our bandwidth for consuming sports. He has other reasons, all of them thoughtful and possibly true, but I think he misses the heart of the matter.

My thoughts below should be, as Tyler Cowen states, filed under “speculative.”

Sports occupies a very large place in our civilizations bandwidth. The growth of the importance of sports, and the money associated with sports, accelerated on a national scale as a few different things happened over the last 50 years:

- Growth of technology allowed people across the country to discover sports hero’s from other locales.

- Beginning around the 1960’s a dramatic moral shift happened that eroded certain key foundations Tocqueville and others cite as necessary to support democracy, such as shared trust and a robust family structure.

- Perhaps we can also cite the growth of suburbia as a factor eroding another key facet of healthy democratic life cited by Tocqueville–local neighborhoods and local institutions and customs.

So as things start to erode on a local and particular level, they homogenized on a national level. Sports benefitted from this, but its growth was necessary, in a sense, to account for the above trends. We lacked local means of conflict mediation on front porches, coffee shops, etc. Sports stepped into that void. Fundamentally, we can understand sports as a highly ritualized, liturgical, and controlled means of combat. For those two hours we can “hate” the team wearing the other jersey, but we know that we don’t really hate them. The liturgy of competition creates a parallel world where we can control conflict. We have all played games against friends–for a time they function as the “enemy,” then real life resumes. Bad sportsmanship means in part the inability to come back to the real world from the parallel world. Whether at cards, basketball, or the like–our competition serves as a way to mediate/navigate our relationships.

Without shared trust, without real communities, we need sports now more than we did 50-100 years ago.

But then–why did the ratings plummet for sports at a time when a need for controlled conflict mediation seems quite high?

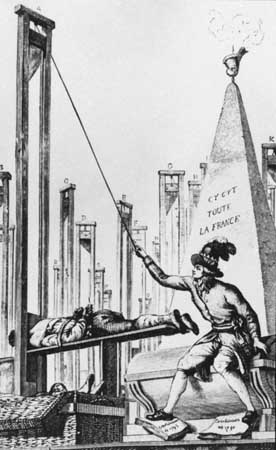

If sports serve as a parallel liturgy of rivalry, we can see that this “conflict” gets resolved via sacrifice. Athletes, then, function in certain ways as priests of this liturgy. We expect them to “sacrifice” for the team, their time, their bodies, etc. Thus, they serve as “victims” in some ways of the liturgy. But in addition, at least our star athletes also control the liturgical space. They ask us to cheer, we cheer. When they complain to the ref, we join in with them–the ref’s call was obviously wrong–and so forth.

If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound? If you have a materialist-leaning view of the universe, the answer is an obvious ‘yes.’ You can ‘prove’ your point by recording the event with no one around, and then listening to the recording. You hear the tree falling and presto, you have your answer. But if you have something of an ‘idealist’ view of the world, as did Bishop Berkeley,* you answer in the negative. Is there “sound” on that recording? Can you carry around “sound” that you do not hear? It seems to me that for reality to be Real it requires perception.

This idea closely relates to the dictum in both Catholic and Orthodox churches (and perhaps others) that no priest can celebrate the sacrifice of the mass alone–though of course certain unusual exceptions allow for it. Many reasons exist for this restriction, but briefly:

- The sacrifice of the mass is always for the people–the body of Christ, and not merely the priest.

- The priest, representing Christ, cannot be the sole ‘beneficiary’ of the mass, just as Christ did not “benefit” from His own death (of course He does “benefit” in the end, but I trust all take my meaning).

- The “power” of the sacrifice has to “land” to take form and reality. Without this “landing” the sacrifice has no power and no life to give.

- The Head (Christ) must nourish the body. Just as we take in physical nourishment through our mouths, so too–what is the point of the sacrifice of food (for all food was once alive and now has died that we might have life) if we have no body? The food–which has already undergone death, will not be transformed into life for us, but rather, stay “dead” as it falls out of our throats onto the floor. Or to put it another way, maybe Berkeley was right about trees falling in forests all by their lonesome.

All well and good, but this fancy talk, some might say, forgets that the televised sporting events do have witnesses, both in person and at home. Most watched at home anyway in the first place before the virus hit. Very little has changed about how the vast majority of us consume sports now except the immediate social factors Frank listed above.

Well, I concede partially. But just as virtual church is not church, and a virtual concert is no real concert–a virtual sporting event is not a real sporting event. Anyone who has watched on tv senses this. The viewers themselves sense it, which is why teams pipe in crowd noise. It is a trick meant to fool those watching at home more than the players, I think. The “sacrifice” of sports needs a place to land within the “church”/arena. If it disappears into the ether, its power disperses with it.**

The ratings decline in sports confuse us only if we fail to see connections between liturgical worship and sports.

Dave

*I do not claim to understand more than the bare outline of Berkeley’s premises, and could not defend his general philosophy even if I wanted to.

**We can also consider the sudden collapse of Rome’s gladiatorial games in the mid-4th century. No question–one main factor had to be the rise of the Christian ethic. But the growth of the games themselves also had something to do with it. When one man fought one man in front of 50,000, whatever took place would be witnessed and participated in by all. But as the games grew in importance they grew in scope, and the cruelty of the games grew more random and bizarre. As the games (unknowingly) neared the precipice, dozens of men fought other dozens of others more or less randomly.

At that point, if you were a gladiator you could not be sure that anything that happened would be directly seen by anyone. One could kill or die with honor and dignity and who knows who witnessed it? If nothing is affirmed, nothing glorified, then why fight at all? With no glory possible, only chaotic death remains. Why would a Roman citizen want to witness a “nothing?”