I consider myself a mild agnostic on certain things about the ancient past.

I have no firm commitments about the age of the Earth. I also have no commitment to the development of life on a macroevolutionary scale, thus I have no need for a very old earth. As much as I understand the science, it looks like the earth (or at least the universe) has a very, very long history. But I am intrigued by some young-earth arguments on the periphery out of curiosity. Among other things, a lot of ‘old-earth’ arguments don’t take into account a cataclysmic worldwide flood. If such an event happened, geological dating would need recalibrating.

When it comes to the book of Genesis, my commitments get deeper. I am open to both literal and ‘mythopoetic’ interpretations of the early chapters of Genesis. We can also combine them and probably both methods have their place. But certain messages seem absolutely clear, among them:

- That humanity fell from a state of grace, innocence, peace, etc. into a type of chaos

- That our sin fundamentally altered the nature of human existence

- That the change in humanity was physical as well as spiritual. One may not believe that the lifespans given in Genesis are literal. But the pattern is clear. Adam and the earliest humans lived much longer than those at the end of the book. By the end of Genesis we see that something about humanity has changed drastically.

- The formation of civilizations happens very quickly. It is almost the default mechanism of humanity. Cain builds cities right away. After the flood we have the Tower of Babel, and so on.

This reading of Genesis informs my reading of ancient history.

There is a version of early pre-history, common in most textbooks, that runs like so:

- The earliest humans were basically ignorant and violent hunter-gatherers that lived in small groups.

- At some point the climate changes or the herds thin out. Food resources dwindle, forcing them to cooperate with larger groups to survive.

- Because now you have to stick close to water, you get rooted to a particular spot. You can’t just follow the herds.

- So, you invent agriculture. When you have really good harvests, you have a surplus.

- This surplus gives the group leisure. With this leisure they build more tools. Eventually they build governments and laws.

- As society expands governments have a harder time holding everything together. So, they either invent religious practices or codify them in some way for the masses, which finishes the development of civilization.

This view is called “gradualism” or “evolutionary gradualism” or something like that.

I entirely disagree with this view. The book of Genesis certainly at bare minimum strongly hints at something much more akin to devolution, and myths from other cultures hint at the same thing.

Enter Graham Hancock.

I don’t know exactly what to make of him. The fact that he is an amateur bothers me not at all. Those very familiar with this blog know of my love for Arnold Toynbee, and one of his main causes involved championing the amateur historian. He makes no claims to fully understand some of the science he cites but relies on others with special degrees. You can’t fault him for this.

He also has a restless curiosity about the ancient world that I love. He willingly dives into unusual theories with a seemingly open mind. His understanding of Christianity is deeply flawed. But . . . his argument against the evolutionary development of religion could have come from any Christian. Many evolutionary theorists acknowledge the social utility and advantage of religious belief. But, he argues, there would be no obvious evolutionary advantage to saying, “We must take time and effort away from survival, making weapons, improving our shelter, etc. to build a large structure for a god that, fundamentally, we are making up. In the evolutionary model it makes no sense that anyone would think of this and that others would somehow agree. Or, you would have to believe that the intelligent people that planned and built these temples were tremendously deluded, and furthermore, that this delusion occurred in every culture. To crown it, if all we have is matter in motion, how would anyone think of something beyond matter in the first place?

Magicians of the Gods has some flaws. It bounces around too much for my taste, and in some  sections of the book the arguments change. One review stated that,

sections of the book the arguments change. One review stated that,

Speaking as someone who found [Hancock’s earlier book] Fingerprints of the Gods to be entertaining and engaging, even when it was wrong, I can say that Magicians of the Gods is not a good book by either the standards of entertainment or science. It is Hancock at his worst: angry, petulant, and slipshod. Hancock assumes readers have already read and remembered all of his previous books going back decades, and his new book fails to stand on its own either as an argument or as a piece of literature. It is an update and an appendix masquerading as a revelation. This much is evident from the amount of material Hancock asks readers to return to Fingerprints to consult, and the number of references—bad, secondary ones—he copies wholesale from the earlier book, or cites directly to himself in that book.

Alas, I agree with some of these criticisms. But I think some of them miss the overall point Hancock attempts to make.

When evaluating Hancock v. the Scientific Establishment, we should consider the following:

- Arguments in the book involve interpretations of archaeology and geology, two branches of science that are relatively young, both of which have to make conclusions based on a variety of circumstantial evidence. Science usually comes down hard on circumstantial evidence, and “proof” is hard to come by in these disciplines. But some that attack Hancock do so when he suggests or speculates, and then blame him for not having “proof.”

- Hancock is right to say that the Scientific Establishment is too conservative. But, this is probably a good thing that Science is this way. This is how Science operates.

- Hancock cites a variety of specialists and laments that the “Establishment” pays them little heed. I think that some of these “fringe” scientists may truly be on to something that the conservatism of the academy wants to ignore. But . . . some of them may be ignored by the academy because they are doing bad science. How does the layman decide when degreed specialists radically disagree? We may need a paradigm outside of science to judge. In any case, Hancock too often assumes that scientists with alternative ideas get rejected only for reasons that have nothing to do with science.

- Some reviews give Hancock a hard time for referencing earlier books of his. This can be annoying, but . . . on a few occasions Hancock references his earlier books to disagree with or modify his earlier conclusions. In the 20 years since he wrote Fingerprints of the Gods he has “pulled back” from some earlier assertions in light of some new evidence. This seems at least something like a scientific cast of mind, but his critics seem not to have noticed this. Should he be criticized for changing his views?

- His book cover and title might help him sell copies, but it looks too gimmicky, and is guaranteed to draw the suspicion of “Science.”

I wish he made his central point clearer throughout and summed it up forcefully at the end of the book. But we can glean the main thrust of his argument.

First . . .

Emerging evidence exists that a major comet, or series of comets, struck Earth some 12,000 years ago. While this may not yet have the full weight of the scientific establishment behind it, many regard it as an entirely legitimate proposition. It is not a fringe idea.

Many in turn believe that this comet struck to polar ice-caps, causing a flood of literally biblical proportions. Those who believe in the Biblical flood need not ascribe this as the cause, but perhaps it could have been. Of course many other ancient cultures have stories involving a cataclysmic flood.

Well, all this may be interesting, but this had little to do with the history of civilization (so the argument goes) because civilization did not emerge until sometime around 4000 B.C., well after the possible/likely? meteor impact flood.

This brings us to Hancock’s second assertion, that civilization is much older than we think.

The discovery of Gobeki-Tepe some 25 years ago began to revolutionize our understanding of the ancient world.

No one disputes that the site dates to thousands of years before the so-called beginnings of human civilization. The stone work is precise and impressive. Recent radar penetrations indicate that even bigger, likely more impressive stone work lies beneath the site.

Here we come to a fork in the road.

- We can rethink our assumption of early hunter-gatherers. We can assume that they were far more advanced than we originally thought. We can assume that they could organize in large groups and they possessed a high level of development and skill, including that of agriculture. But then, would they be hunter-gatherers if they acted this way?

- Or, we can assume that mingled with hunter-gatherers might have been the holdovers of a previous advanced civilization, perhaps one mostly wiped out by a global cataclysm. These are the “magicians of the gods” Hancock postulates–those that emerged from the mass extinctions caused by global flooding, who perhaps took refuge with hunter-gatherers. Perhaps they had a trade of sorts in mind: 1) You teach us survival skills, and 2) We teach you how to build, plant, and organize.

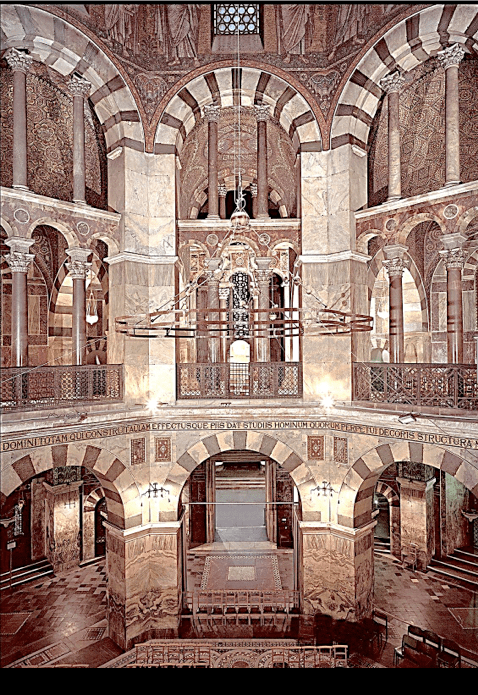

Option 2 might seem crazy. It would probably mean reversing our gradual, evolutionary view of the development of civilization at least in the last 10,000 years. But we have seen something like this already–an undisputed example of it after the fall of Rome. All agree that in almost every respect, Roman civilization of 100 A.D. stood far above early medieval civilization of 800 A.D.

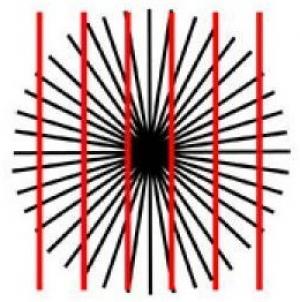

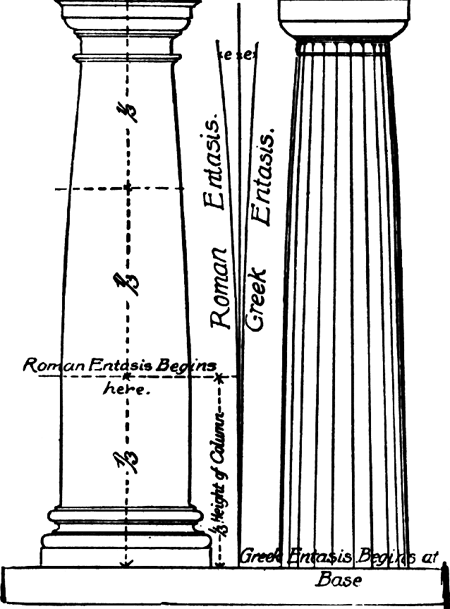

But Gobekli Tepe is not the only example of something like this. Archaeologists observe other sites where earlier architecture seems far more advanced than later architecture. Take, for example, the Sascayhuaman site in Peru, not far from where the Incas developed. This wall, for example,

almost certainly predate the Incas by thousands of years. The Incas later certainly could build things, but not in the same way, as the picture below attests (and it looks like they tried to copy the older design in some respects).

At Gobekli-Tepe, the recently deceased project head Klaus Schmidt commented regarding the parts of the site still underground that, “The truly monumental structures are in the older layers; in the younger layers [i.e., those visible to us at the moment] they get smaller and there is a significant decline in quality.”

Some similar possibilities of much older and possibly more advanced civilizations exist in Indonesia and other sites around the world. For example some believe that the Sphinx was built thousands of years before the pyramids. There is some water erosion evidence that could support this theory. There is also this intriguing ancient alignment with the Sphinx and the Leo constellation:

If true, this could mean that the Egyptians built the Pyramids where they did because they knew the site was already sacred from a previous era, or even possibly, a previous civilization.

With this before us, at bare minimum, we can strongly argue that the standard gradual and uniform process of the development of civilization should be in serious doubt. If we accept this, then two other possibilities follow:

- Some civilizations went through periods of great advancement* and then fell into a period of steep decline, after which they never quite recovered their former glory. A massive flood certainly could have triggered this decline.

- Another possibility is that we may be dealing with different civilizations altogether. Hancock ascribes to this view. For him, sites like Gobeckli Tepe served as a time capsule of sorts, a clue, or a deposit of knowledge for others to use in case of another disaster. This may raise an eyebrow or two, but one of the mysterious aspects of Gobeckli-Tepe that all agree on is that they deliberately buried the site and left it. Who does this? Why? Perhaps they wanted this site preserved so that it could be used in case of another emergency to restart civilization. If this is true, there is much we do not understand at all about this site.

Those that want a tightly knit argument heavily supported by the scientific community will be disappointed by Magicians of the Gods. But for those that want a springboard for rethinking the standard timeline of the ancient world, the book does very nicely.

Dave

*Michael Shurmer of Skeptic magazine argued against Hancock, saying that, “If they were so advanced, where is the writing? Where are the tools?” But why must writing be a pre-requisite for advancement? Or if you believe writing is a hallmark of advancement, what if this previous civilization was more advanced in many other ways? And if they built buildings, isn’t it obvious that they used tools, even if we can’t find them? If they built them without tools, wouldn’t they be really smart?

Maybe no tools exist at the site because they didn’t live near the site, for whatever reason. But where they lived has nothing to do with how advanced they seem to have been. Like Hancock, I’m not sure what else we need other than Gobekli Tepe to prove the point.