J.E. Lendon’s Song of Wrath helped me see the early phases of the Peloponnesian War differently. From a modern perspective a stalemate between Athens and Sparta ca. 431-427 B.C. Sparta could not touch Athens’ navy, Athens could not deal with Sparta’s infantry, and so they danced. Lendon pointed out, however, that the culture of honor that permeated Greece allowed each side to declare victory–not victory over their opponents physical ability to wage war, but victory as a kind of pride of place. Confusion about what exactly constituted victory led to an expansion of the conflict.

This confusion, however, would never have happened had Athens not developed a navy, and broadened their source of strength. The growth of the navy and the growth of Athenian democracy went hand in hand. The growth of the navy meant expanding contact with others, and expanding one’s access to the material wealth of others. The growth of democracy meant more participation and involvement from more people in the daily operations of the state. Both involve movements “down the mountain” toward greater potential, but also towards more instability. This greater “diversity” in sense, would naturally bring about more confusion regarding the application of core values.

History does not always proceed in one direction, but the same patterns and connections emerge over time. “Politics flows downstream from culture,” and culture likewise with religion. This would mean, then, that Greece experienced a theological shift before its political shift. Though I believe in the theory, I am on very shaky ground in my knowledge of the history of Greek religion. But, I venture the theory that the beginnings of Athenian drama hearkened to a more “expansive” Greek religion rooted in the ecstatic reveries of Dionysius. Before, I think, they confined such “madness” to oracles located towards the periphery, and not easily accessed by the general population. Now, with the arrival of Dionysius and the dramatic arts, everyone (in theory) could taste something of such states. Significant democratic reform followed shortly thereafter.

Such is my theory, tenuous at best.

But as we move forward in time, towards epochs more easily observed, I think the connections between religion and ultimately, war itself, have more clarity. Gunther Rothenberg’s The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon makes no connections to religion and culture per se, but his thorough detail and clear analysis give one a good foundation to speculate a bit here and there.

Rothenberg starts with the armies that directly preceded the French Revolution. He focuses on the particular facts “on the ground” that influenced how armies functioned. What appears strange to us about the early-mid 18th century armies is how they often sought to avoid battle, and how quickly and easily generals broke off battles when the outcome appeared even slightly in doubt. We see this with in commanders like Prussia’s Duke of Brunswick, who refused to give battle to French Revolutionary forces at Valmy. No one thought this amiss–he retained the trust of Prussia’s king, changed little, and stayed in command until 1806, when Napoleon destroyed his forces at Jena. He was hardly alone.

A variety of factors helped bring about this template:

- Muskets of the time had very low accuracy, so inflicting serious harm required massing of men to fire. Of course, one’s opponent would also have to mass men to do likewise. Battles where both sides actually fought hard meant very high casualties, such Torgau (1760, 30% casualties) and Zorndorf (1758, 50% casualties).

- Artillery pieces existed, but they were much heavier in 1750 than in 1800. Thus, artillery was much less mobile, meaning that battle had to happen in pre-arranged spots for them to be used, or battle would not happen.

- Enlisted men had a difficult life–desertion was common. To limit this, armies moved slowly, in large formations, supported by supply lines. Foraging, after all, could lead to desertion.

- We talk of bloated military budgets today, but the dawn of professional armies paired with a pre-modern state apparatus meant that the military routinely took up to 25% of annual revenue, or sometimes as much as 50%.

All this meant that many kings and commanders naturally found decisive battle elusive, and casualties enormously expensive.

These factors come from “below,” so to speak. I mean by this that the particulars of strategy and tactics seemingly get created from particular physical details, such as the accuracy of muskets. We should absolutely look at history from this perspective, but we need more. We should speculate what cultural and religious underpinnings helped create these conditions from “above.” Beliefs or ideas helped bring about such conditions, just as you need rain (from above, of course) and soil to make anything grow.

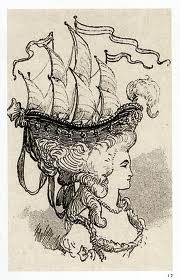

Kenneth Clark pointed out that the Enlightenment defined itself by the “Smile of Reason”–a dignified, reasonable happiness, undergirded by control. Bernard Bouvier, the long-lived French Enlightenment philosophe, remarked that he had never run, and never lost his temper. When asked if he had ever laughed, he replied, “No, I have never made Ha Ha.” The thread throughout–he maintains control over his mind and body. An era devoted to such things would never value glory, which is fundamentally irrational. Also, we cannot measure glory. In a sense, glory requires an abandonment of control. This has in its religious origins “Deism”–a God who has power to create, but a God who “controls himself,” content with the benign “smile of reason.” Deism cannot brook an upsetting of the apple cart.

The French Revolution, from a political and cultural perspective, smashed all of this to pieces, and later, Napoleon finished the job. The roots of this come not from the politics of the French Revolution, but from its antecedent theological revolution.

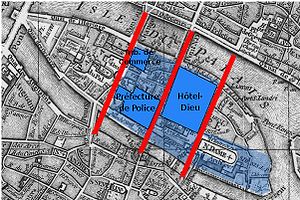

When Louis XVI called together the Estates General, he wanted them to deal with a specific problem of taxation and tax law. Very briefly, the Estates General was comprised of three “estates,” the Church, nobility, and the “everybody else.” Each block voted as an estate, and 2 out of 3 wins. The clergy and nobility represented perhaps 5% of the population, so the third estate naturally (on this side of the American Revolution) did not want shut out by a vast minority. They insisted that Louis disband the three estates and create a new National Assembly, which would eliminate the “Estates” and obviously give the masses much more say.

This demand makes perfect sense to us, and likely we can only interpret Louis’ initial objections to this as stick-in-the-mud obscurantism. But this request contained the kernels of much more than a political revolution. We see this by looking at the medieval view of God and political power.

We know that we exist, we know that things around us exist. But in a truer sense, only God exists. That is, only God exists in a completely self-sufficient way. We need water, food, etc., to keep our existence, among other things. More importantly, we exist only because God exists–“in Him we live and move and have our being.”

God certainly has no need of us to do anything He wants done. But He creates out of fulness, out of love, to share. God shares something of His existence as well as His power. But we cannot fully participate in God’s essence–“No one has seen God at any time.” We can however, participate in His “energies,” or–in “parts” of God doled out to us (though of course God has no “parts”). Genesis 1 shows us that we cannot take everything into ourselves “in full.”

The same holds for power. In the truest sense, only God has power to accomplish His will and purpose. But, he shares, and just as He shares with us existence, so too He grants us agency and will. But we cannot have power concentrated all together. Reality, and power, must be separated and made distinct for us to have dominion over it. The works of St. Dionysius the Areopagite, hugely influential in the medieval era, make a similar point. Heaven has a distinct hierarchy, present most particularly in the angelic hosts, that we should mimic on earth, as we pray in the Lord’s Prayer–“thy will be done, on earth as it is in Heaven.”

So, a governments separation of powers has particular theological roots, with a definite social and cultural purpose. If we think of the three “estates” in France, certainly the Church should not blend/meld with the world around it, lest it be captured by the world. An aristocracy in part provides guides for culture and taste. In theory, they elevate culture through their patronage and example. To blend them in with everyone else would eliminate their distinctiveness, and culture would descend to the lower level of pork rinds and Youtube fails.*

This religious shift away from traditional understanding gave way to a very different kind of army and different kinds of wars. For starters, the jumbling up of everything and the resulting political chaos meant that the French army under the Revolution had much fewer supplies. This in turn meant that the French armies had to forage for their food. But having no supply lines also made the army more mobile. It in turn made the army more offensively oriented. If you want to eat, win the next battle and take what you can from the enemy. Napoleon said as much to his army in Italy in 1796.

Tocqueville noted the immense potential power of democratic armies which comes from the concentration of resources. To reference the mountain pattern I mentioned earlier, the base has the most mass. This increase of power would not easily be contained. With the full embrace of the descent down the mountain in Romantic ideology came a dramatic increase in the ferocity of how the French fought. Rothenburg cites a variety of examples of this. St. Just (Robespierre’s lieutenant) declared that the army should emphasize “shock tactics.” Carnot, the premier military engineer of the Revolution told his generals that,

The general instructions are always to maneuver in mass and offensively; to maintain strict, but not overly meticulous discipline . . . and to use the bayonet on every occasion.

Both Carnot and St. Just both intuited the meaning of the religious and political changes for the tactics of the French army, and perhaps this synchronization made the army so effective. Gone were the days of elegant and precise movements of armies, enter the ferocity of the massed charge. Rothenberg also shows that the French revolutionary government proved much more effective at supplying bullets than food to its army, which fits the pattern above.

Napoleon inherited rather instigated these changes, but his keen intuitive sense and knack for precise detail gave the French army a direction and impetus it previously lacked. The religion of Romanticism had its apotheosis here. The political concentration that began with the Three Estates merging into the National Assembly eventually finds Napoleon to finish the job.

We need not debate Napoleon’s great strengths as a leader, but they came at a.price. Most militaries have different armies within their Army, i.e., First Army Group, Second Army Group, etc. But Napoleon had just one army, the “Grand Army.” Just as France was One, so too would the army function as One, with one in command of all. This extreme unity of command came from Napoleon’s large ego, but also from the Revolution’s hatred of “Federalism.” Being a “federalist,” which meant wanting a separation of powers within the state, could easily get one executed between 1792-94. Such a strong reaction to a political concept demonstrates the religious roots of the change. Desire for something other than extreme unity meant something akin to an existential threat. Rothenberg notes that when Napoleon had command of the field the French did very well. But when he could not be present, and had to delegate command, as in Spain, the French army collapsed.

This concentration of power influenced everything about Napoleon’s governance, strategy, and tactics.

- Napoleon naturally wanted to screen the path of the army’s advance, so he controlled borders, controlled information, prevented foreigners from staying in the country, and so on. Such control was unheard of in his day.

- Because Napoleon needed total control to accomplish his strategic design of one decisive blow, he valued commanders with physical bravery as their main (and only?) virtue. Certainly commanders need courage, but Napoleon cared very little for intelligence, creativity, initiative, etc. He wanted generals that served mainly as instruments of his will.

- Napoleon’s goal to win via one decisive blow required all that has already been said, but in addition, he needed a certain type of geography, as at Friedland, for example. He needed a space where he could force, or perhaps lure, his opponents in an all or nothing contest. When his opponents could easily withdraw with depth (as in Russia, most obviously) he had real problems.

Napoleon mastered the tactics of the crushing, decisive blow, but perhaps he inherited the strategy. Robespierre wrote in 1794 that,

The two opposing spirits that have been represented in a struggle to rule nature might be said to be fighting in this great period of human history to fix irrevocably the world’s destinies, and France is the scene of this fearful combat. Without, all the tyrants encircle you; within, all tyranny’s friends conspire; they will conspire until hope is wrested from crime. We must smother the internal and external enemies of the Republic or perish with it; now in this situation, the first maxim of your policy ought to be to lead the people by reason and the people’s enemies by terror.

If the spring of popular government in time of peace is virtue, the springs of popular government in revolution are at once virtue and terror: virtue, without which terror is fatal; terror, without which virtue is powerless. Terror is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible; it is therefore an emanation of virtue; it is not so much a special principle as it is a consequence of the general principle of democracy applied to our country’s most urgent needs.

It has been said that terror is the principle of despotic government. Does your government therefore resemble despotism? Yes, as the sword that gleams in the hands of the heroes of liberty resembles that with which the henchmen of tyranny are armed. Let the despot govern by terror his brutalized subjects; he is right, as a despot. Subdue by terror the enemies of liberty, and you will be right, as founders of the Republic.

Napoleon’s own words after his participation in the siege of Toulon in 1793 differ little from Robespierre:

Among so many conflicting ideas and so many different perspectives, the honest man is confused and distressed and the skeptic becomes wicked . . . Since one must take sides, one might as well choose the side that is victorious, the side that devastates, loots, and burns. Considering the alternative, it is better to eat than be eaten.

My point here is not to equate Robespierre with Napoleon–I would rather have neither, but would much prefer Napoleon to Robespierre–nor even to morally condemn him. Politics is a dirty but necessary business. Instead, I think we should see a connection between the religious changes brought about by Rousseau, and see how it filters down into why Napoleon’s armies smashed through Europe. At the Congress of Vienna, we can see how the extremes of unity would inevitably swing back to making borders preeminent, and then, to nationalism in the latter 19th century.

With the rise of China, crypto, the war in Ukraine, twitter, and so on, most everyone has the sense that the world is changing, and most everyone disagrees on the meaning or direction of the change. We might get more clarity if we looked at how religion has changed over the last 30 years or so, which might equip us to head some things off at the pass.

Dave

*I don’t mean to be a high-brow curmudgeon. “Low” culture can and should exist. My point here is that most of the time that we want to partake of “high” culture we have to go back to pre-democratic ages, a Michelangelo statue, a Bach cantata, etc. Democratic cultures can produce “high” culture, but I would submit that they cannot create as much and not the same enduring quality. I also acknowledge, however, that not enough time has elapsed for democratic culture to be fairly judged.