I have written on a few occasions that those who write history books can fall into one of two errors:

- Over-emphasizing the differences between things, which means that nothing can be compared to anything with any confidence, and

- Over-emphasizing the similarities between things, which these days means that everyone is either Hitler or Stalin.

The best historians combine factual mastery with poetic gifts. They see rhyme and rhythm, but they never force it, letting the “occasional” square pegs stand aside from the round holes when appropriate.*

The first error (the “differences” error) is more useful. If you over-emphasize particular facts at the expense of synthesis, you have hopefully uncovered many useful pieces of information. But these kinds of historians are in my view not really historians, but researchers. They have definite skills, but play too close to the vest. Without extending themselves and taking a risk, they limit their impact.

The second error involves more chutzpah and dash, and so I tend to be more forgiving to those who synthesize too much. Toynbee, one of my great heroes, conflated Greek and Roman civilizations to such a degree that he claimed that Rome began its decline in 431 B.C., the year the Peloponnesian War started in Greece. Such an assertion perhaps has some grandeur in its theatricality. But no one could claim that this whopper arose from intellectual laziness on his part.

Other times, however, errors of the second kind can only arise from a combination of laziness and willful blindness. These types of errors of the “Over-emphasizing similarities” school are more dangerous than the “differences” school. When you aim higher, you fall farther.

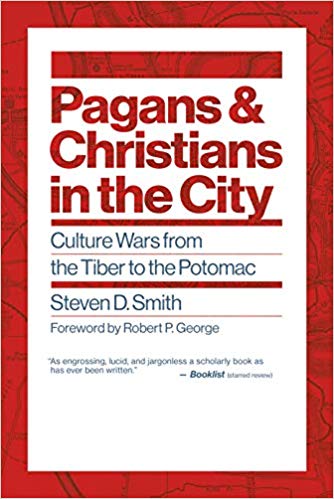

One “similarities” error that has lingered on in the scholarship of late antiquity, and subsequently in the public consciousness, involves the interplay between Christianity post-Constantine and the older paganism. Sir Geoffrey Elton–a knight no less!–expresses this basic idea concisely, writing,

. . . religions organized in powerful churches and in command of the field persecute as a matter of course and tend to regard toleration as a sign of weakness or even wickedness towards whatever deity they worship. Among the religious, toleration is demanded by the persecuted who need it if they are to be triumphant, when, all too often, they then persecute in their turn. . . . To say this is not cynicism but sobriety of judgment.

Ugh–one can just imagine Sir Geoffrey Elton saying this with some British smugness. Intolerable, I say! It just won’t do!

So, Elton, followed by Peter Garnsey, and Francois Paschoud on the French side–and a host of others–mash everything up and declare that basically no difference existed between the intolerance of Rome towards Christians, and intolerance of Christians towards Roman pagans.

But even a brief look at this assertion shows its utter fatuity.

How did Rome persecute Christians? Over a span of 250 years (though not continuous over that period, but sporadic in its intensity) Rome imprisoned, tortured and killed thousands and thousands of Christians. Many died in a gruesome manner, as even Roman sources hostile to Christians attest. By the late empire, feeding Christians to lions in the arena was old hat. Even mild, tolerant, and “good” emperors like Trajan admitted that, yes, if push came to shove, Pliny should arrest and even execute Christians.

How did Christians persecute pagan Romans once in “command of the field?” They closed and sometimes destroyed temples. They refused to give state funding for pagan rites. They closed the Academy of Athens. Some sporadic–and important to note–non-state sponsored violence probably happened in some instances. One can cite the era of Theodosius I, from AD 379-395, where

hands and feet . . . were broken; their faces and genitals smashed . . .

But this violence was not directed at people but at the statues of gods and goddesses. However “purposeful” and “vindictive” (as one historian terms it) such actions may have been, it is not quite the same thing as watching people eaten alive for entertainment.**

Enter historian Peter Brown to set the record partially aright. Alas, I have only slight exposure to Brown, an acknowledged master of late Roman antiquity. My first impressions peg him tending towards the “differences” error, but this might suit him well to clean up the typical sludge created by Elton et. al. on this issue. He entitled chapter 1 of his work Authority and the Sacred: Aspects of the Christianization of the Roman World, “Christianization: Narratives and Processes,” which can only elicit one response:

But chapter two deals with the question of religious toleration in a much more promising manner.

Brown points out a few helpful counterpoints to Elton and his crew.

Most every ruler’s first priority involves money, which comes mostly through taxation. Any ruler of moderate ability understands the tricky nature of taxation, and how it relies upon a network of trust and compliance that is not easily enforced. Brown comments,

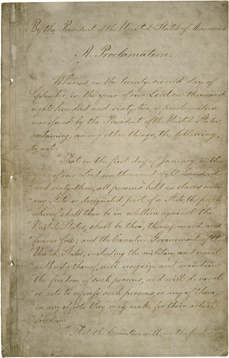

It is easy to assume that a tax system . . . so successful, indicated the indomitable will of the emperors to control the souls of their subjects as surely as they had come to control their wealth. In fact, the exact opposite may be the case. In most areas, the system of negotiated consensus was usually stretched to its limits by the task of exacting taxes. It had little energy left to give ‘bite’ to intolerant policies in matters of religion. It is no surprise that many sources indicate a clear relation between taxation and toleration. Faced by demands of Porphyry of Gaza for permission to destroy the temples of the city, supposedly in 400, the emperor Arcadius is presented as having said: ‘I know the city is full of idols, but it shows “devotio” in paying taxes and contributes much to the treasury. If we suddenly terrorize these people, they will run away, and we lose considerable revenues.”

Brown also stresses that late imperial Rome even in the Christian era involved shared power among elites. And these elites had strong common bonds between them that crossed religious lines. Brown writes again,

As far as the formation of the new governing class of the post-Constantinian empire was concerned, the fourth century was very definitely not a century overshadowed by [religious conflict]. Nothing could have been more distressing to the Roman upper-classes than the suggestion that ‘Pagan’ and ‘Christian’ were overriding designations in their style of life and choice of friends and allies. . . . Rather . . . studied ambiguity and strong loyalty to common symbolic forms . . . prevailed at this time.

Pagan and Jewish religious leaders, Brown notes, received not just toleration, but sometimes even support from the empire.

It would be wrong to imply, as Menachem Stern has done, that [Libanius and the rabbi Hillel] . . . found themselves drawn together “under the yoke of Christian emperors.” They were drawn together by common enjoyment of an imperial system that conferred high status on them both. . . . Both enjoyed high honorary rank, conferred by imperial codicilli–those precious purple letters of personal esteem signed by Theodosius in his own hand.

Theodosius, it bears mentioning, is often thought of as one of the great “intolerant” emperors.

So far, well and good. Brown, with his eye for detail and his great reluctance to generalize, gives an admirable riposte to the traditional academic narrative. But something still needs addressed. Brown blocks effectively, but asserts little beyond, “It wasn’t as clear cut as many think,” he seems to say. But everything is complicated. The historian should at least offer a way to make the complicated intelligible.

Alas, the elephant is still in the room, in the form of two important questions for scholars like Elton and Garnsey–questions that Brown fails to ask:

The first: toleration may be a good thing, but what are its limits? One can praise the virtue of getting along despite differences. Everyone knows this already, however. It’s not a hard thing to say. The hard thing means saying when the differences have become so great that co-existence no longer works, when the house divided cannot stand.

Drawing this line ultimately comes down to values, and values come from religious beliefs. My second question to Elton, etc. would be, “What is your religion? You seem to be neither pagan, nor Christian–and that’s fine. But what or who is your God/god? And what does He/She/It not like? What do you not tolerate? Surely He/She/It can’t like everything.

Brown avoids such questions, and that’s too bad. He has my respect, and a historian of his heft should apply his knowledge to this problem. As for our own situation in our own time, such questions have unfortunately become more than just theoretical. I believe that the media accentuates the differences between Americans for profit. Also, professional tweeters are more divided than average Americans. But a breaking point lies out there somewhere for all of us. We must acknowledge this, and at the same time, hope that we never find it.

Dave

*This observation might seem quite obvious, and so it is. But it is rooted in the profound truth of the nature of the Trinity–unity and diversity at the root of all being.

**I admit this is not the whole truth of all of Christian history. There were times and places where it got worse than this in the next 1000 years. But though it did at times get worse than what I describe above, it never equaled what Rome did.