“Whatever we may think of Alexander–whether Great or only lucky, a civilizer or a sociopath–most people do not regard him as a religious leader. And yet religion permeated all aspects of his career.”

This opening line of the book blurb for F.S. Naiden’s Soldier, Priest, and God: A Life of Alexander the Great, sucked me right in. I too had viewed Alexander nearly solely through a narrow political and moral lens, and had never really considered his religious views and acts as central to his successes and failures. The book was too long for me. I would have preferred if he assumed reader knowledge of the standard elements of the Alexander narrative. But what Naiden draws out from his expertise in ancient religious rituals helps us see Alexander afresh in certain ways.

Historians tend to think about Alexander along three standard deviations:

- Great visionary and magnificent strategist, one of the truly “Great Men” that, naturally, and tragically, few could truly follow

- Fantastic military leader with flawed political skills. After Gaugemela in 331 B.C., his political skills become more necessary than his military skills, and so his fortune waned and his decisions got worse

- A thug and barbarian who lived for the chase and the kill. He never really changed, or “declined,”–he always was a killer and remained so until his death.

Soldier, Priest, and God tries to bypass all of these paradigms, though touches on each in turn. Naiden’s Alexander is a man who mastered much of the trappings and theater of Greek religion, which included

- The hunt

- Prowess in battle

- A religious bond with his “Companions,”–most of whom were in the elite cavalry units.

- Responding properly to suppliants

As he entered into the western part of the Persian empire, i.e., Asia Minor, he encountered many similar kinds of religious rituals and expectations. The common bonds and expectations between he and his men could hold in Asia Minor. But the religious terrain changed as Alexander left Babylon (his experience in Egypt had already put some strain between he and his men, but it could be viewed as a “one-off” on the margins), and he had to adopt entirely new religious forms and rituals to extend his conquest.

Here, Naiden tacitly argues, we have the central reason for Alexander’s failures after the death of Darius. Some examples of Naiden’s new insights . . .

Alexander’s men did not want to follow him into India-they wanted to go home. Some view this in “great man” terms–his men could not share Alexander’s vision. Some view this in political/managerial terms–his army signed on to punish Persia for invading Greece. Having accomplished this, their desire to return was entirely natural and “contractual.” Naiden splits the horns of this dilemma, focusing on the religious aspects of their travels east.

Following Alexander into the Hindu Kush meant far fewer spoils for the men. Some see the army as purely selfish here–hadn’t Alexander already made them rich? But sharing in the spoils formed a crucial part of the bonds of the “Companions.” The Companions were not just friends, as Philip had created a religious cult of sorts of the companions. It wasn’t just that going further east would mean more glory for Alexander and no stuff for his men. It meant a breaking of fellowship and religious ritual. This, perhaps more so than the army being homesick, or tired, led to Alexander having to turn back to Babylon.

Alexander killed Philotas for allegedly taking part in a conspiracy against him. Others see this as either Alexander’s crass political calculus, or a sign of megalomania, or paranoia. Naiden sees this action in religious terms.

- Philotas was a Companion. To execute him on the flimsy grounds Alexander possessed could amount to oath-breaking by Alexander, a dangerous religious precedent. “Companionship” bound the two together religiously, not just fraternally.

- Philotas did not admit his guilt but presented himself as a suppliant to Alexander and asked for mercy. True–not every suppliant had their request granted, but Philotas fit the bill of one who should normally have his request met.

Killing Philotas, and subsequently Philotas’ father Parmenio (likely one of the original Companions under Philip), should be seen through a religious lens and not primarily psychologically (Alexander is going crazy) or politically (politics is a dirty business, no getting around it, etc.).

We also get additional perspective on the death of Cleitus the Black. We know that he was killed largely because of the heavy drinking engaged by all during a party. We know too that Cleitus had in some ways just received a promotion. Alexander wanted him to leave the army, stay behind and serve as a governor/satrap of some territory. Why then was Cleitus so upset? Naiden points out that Alexander had not so much promoted Cleitus, but made him a subject of himself, as well as exiling him from the other Companions. The Companions shared in the spoils equally, and addressed each other as equals. As satrap, Cleitus would have to address Alexander as king and treat him as other satraps treated the King of Persia. Hence, the taunt of Cleitus (who had saved Alexander’s life at the battle of Granicus), “this is the hand that saved you on that day!” came not just from wounded pride, but as an accusation against Alexander’s religious conversion of sorts. Alexander had abandoned the “Equality” tenet of faith central to the Companions.

We can imagine this tension if we put in modern religious terms (though the parallels do fall short):

- Imagine Alexander and his men are Baptists of a particular stripe. They grew up in Sunday school, reciting the “Baptist Faith and Message.” They join Alexander to punish Moslems who had tried to hurt other Baptists.

- As they conquer, they link up with other Baptists. There are Southern Baptists, Regular Baptists, Primitive Baptists, and so on. They go to worship with these people, and while it might be a bit different, it is still familiar. All is good.

- Flush with success, the go further. Now they meet more varieties of Protestants–some non-denominational churches, Lutherans, Presbyterians, some Assemblies of God, etc. Ok, from a traditional Baptist perspective, it’s getting a little weird, but we are still more or less on familiar ground.

- Now we go to Egypt and–what!–Alexander seems to be joining in on a Catholic service. Ok, this is bad, but at least very few in the army saw this, and we don’t have to spread the news.

- Now as we get into Bactria and India Alexander seems to be converting to something unrecognizable. He seems to be breaking with the Baptist Faith and Message and repudiating his past. Or is he? He might be converting to Islam, or what else, I have no idea. We can no longer worship with him. In hindsight, his killing of Philotas was a decisive move in this “conversion.”

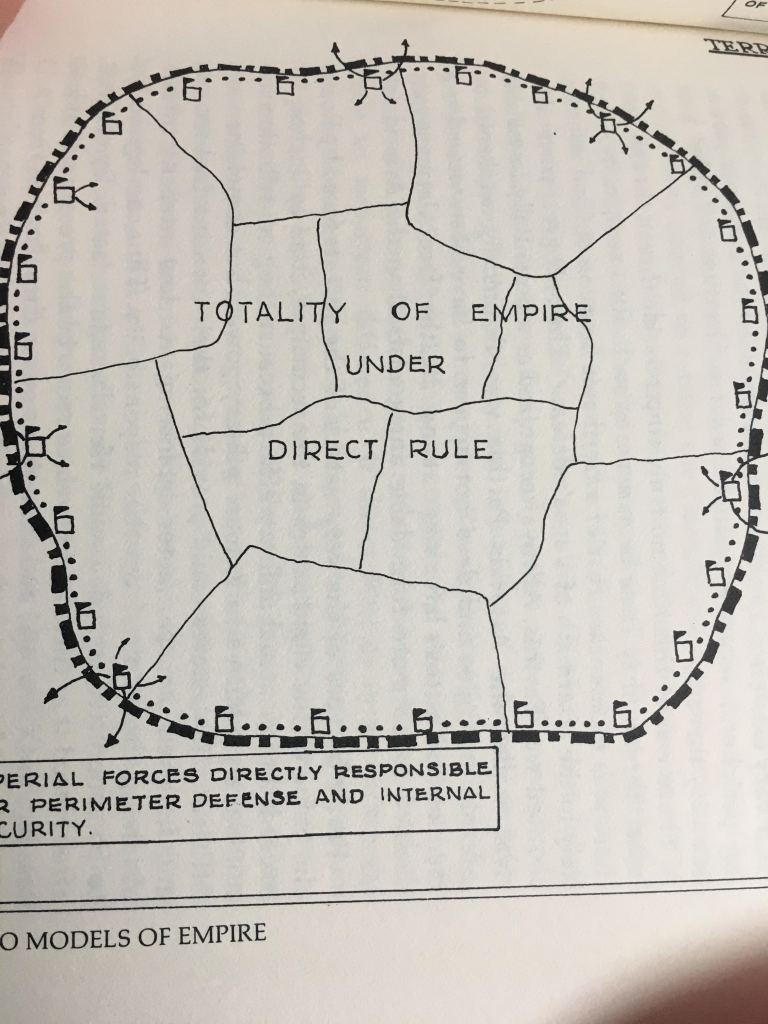

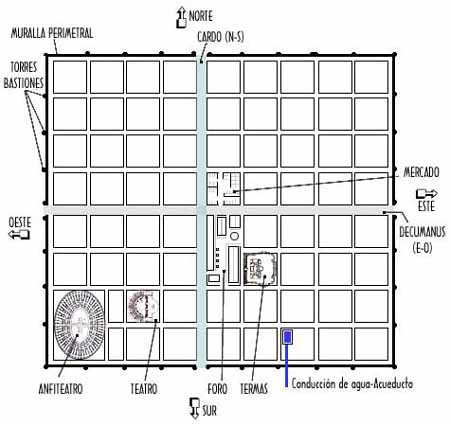

Naiden points out that Alexander never officially becomes king of Persia, and attributes this largely to the religious ideology behind the Persian monarchy that Alexander could not quite share or, perhaps understand. As he went into Bactria and beyond, not only had he grown religiously distant from his men, but he could no longer understand or adapt to the religions he encountered. He found himself constantly torn between acting as a king to those he conquered, and as a Companion to his army. In the end he could not reconcile the two competing claims, and perhaps no one could.

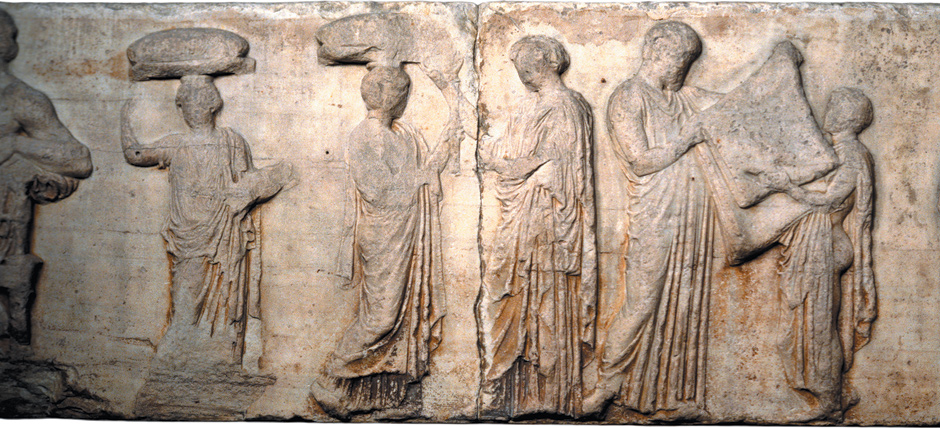

Alexander stands as perhaps the most universal figure from the ancient world. Obviously the Greeks wrote about him, as did the Romans, but stories cropped up about him in India, Egypt, Israel, Byzantium, and within Islam as well. Naiden mentions this but fails to explore its meaning. Naiden has a remarkable ability to find facts and present a different perspective. But he never explores how and why most every ancient and pre-modern culture found in Alexander something universal. Though it will strike many as strange the most common image of Alexander has him not riding into battle on his famous horse, but ascending into the heavens, holding out meat so that large birds will carry him up into the sky.

This image comes from a medieval Russian cathedral:

The story comes from the famous Alexander Romance, and runs like so:

Then I [Alexander] began to ask myself if this place was really the end of the world, where the sky touched the earth. I wanted to discover the truth, and so I gave orders to capture the two birds that we saw nearby. They were very large, white birds, very strong but tame. They did not fly away when they saw us. Some soldiers climbed on their backs, hung on, and flew off with them. The birds fed on carrion, so that they were attracted to our camp by our many dead horses.

I ordered that the birds be captured, and given no food for three days. I had for myself a yoke constructed from wood and tied this to their throats. Then I had an ox-skin made into a large bag, fixed it to the yoke, and climbed in. I held two spears, each about 10 feet long, with horse meat on their tips. At once the birds soared up to seize the meat, and I rose up with them into the air, until I thought I must be close to the sky. I shivered all over due to the extreme cold.

Soon a creature in the form of a man approached me and said, “O Alexander, you have not yet secured the whole earth, and are you now exploring the heavens? Return to earth quickly, or you will become food for these birds. Look down on earth, Alexander!” I looked down, somewhat afraid, and I saw a great snake, curled up, and in the middle of the snake a tiny circle like a threshing-floor.

Then my companion said to me, “Point your spear at the threshing-floor, for that is the world. The snake is the sea that surrounds the world.”

Admonished by Providence above, I returned to earth, landing about seven days journey from my army. I was now frozen and half-dead. Where I landed I found one of my satraps under my command; borrowing 300 horses, I returned to my camp. Now I have decided to make no more attempts at the impossible. Farewell.

Here we have the key to understanding the meaning of Alexander as the ancient world saw him.*

The person of a king becomes the focal point of “bodies.” For example, a single, jobless, man living alone in his parent’s basement has only himself as a “body.” His identity includes only himself–his identity includes nothing outside of himself. Thus, he grows stale. Now imagine said man gets a job. He adds the identity of others to his own. If he gets married, now he has bound his identity to another person. This is why marriage has always been viewed as a religious rite within almost every society past and present, Christian or otherwise. Only God/the gods can effect this kind of change in a person. Then the couple has children, and the man has added more “body” to himself. Then one day he has grandchildren and ascends to the level of “paterfamilias.” His “body” includes multiple families.

A king of Macedon has more “body” than the average Macedonian. As we have seen, Macedonian kingship didn’t function like kingship elsewhere, either politically or religiously. Still, kingship has roots in every culture. But everyone knew that this kind of adding of body involved something of a risky and religious transformation–something akin to marriage. If one goes too far you risk losing everything. We can think of Alexander as holding folded laundry in his hand. He bends down to pick up a book, and can do that, then a plate, and it works, then a cup, etc.–but eventually one reaches a limit as to what you can add to oneself, and everything falls to the floor.

I have written before about the biblical image of the mountain in Genesis. Adam and Eve seek to add something to themselves that they should not. As a result they must descend down the paradisal mountain, where more multiplicity exists, and less unity. This leads to a fracturing of their being, and ultimately violence. This is King Solomon’s story as well. He receives great wisdom–the ability to take in knowledge from multiple sources and achieve penetrating insights (many scholars have noted that the biblical books traditionally ascribed to him contain tropes and fragments from cultures outside of Israel). But he goes too far–he strives for too much multiplicity, too much “adding of body,” as is evidenced by his hundreds of marriages to “foreign women.” This brings about the dissolution of his kingdom, the same result Alexander experienced after his own death. But before Alexander lost his kingdom, many would say he lost himself, with executions, massacres, and other erratic behavior. Like Solomon, he lost his own personal center in his attempt to add body to himself ad infinitum.

The story of the Ascension of Alexander hits on these same themes. He tries to ascend to a unity of the multiplicity through the multiplicity itself (note the use of body in the form of the meat to accomplish this). But it can never work this way. When you attempt to ascend via a Tower of Babel, you get sent back down.

The universality of this problem manifests itself today in these two kinds of people:

- Purists who believe that even the slightest deviation from an original aim or interpretation destroys everything. Things here get so dry and lifeless that it brings the “death” of the desert.

- Compromisers who want to stretch anything and everything to fit anything and everything. No exception ever endangers the rule–everything can always be included. Here you have the flood–undifferentiated chaos with nothing holding anything together. Eventually you reach points of absurd contradiction, and then, conflict.

Alexander’s life fits this tension between purity/unity and multiplicity:

- He could take in Greece

- He could take in Asia Minor

- Perhaps he could just barely take in Egypt

- But beyond that–though he could “eat” other kingdoms further east, they certainly didn’t agree with him.

Indeed, why invoke a blessing from God on food before we eat? We ask, in fact, for a kind of miracle–that things dead might be made life-giving. We too ask for help on the potentially treacherous path of making that which is “not us” a beneficial part of our being. We cannot have real unity without multiplicity, and vice-versa. But no blessing will save us from every deliberate choice to drink from the firehose and ingest foreign gods.

Dave

*Understanding this episode in The Alexander Romance will clue us in on how to read ancient texts. We should not assume that the ancients believed that this story was true in a scientific or “literal” sense. It was true in a more profound, metaphorical, and spiritual sense.