Greetings,

This week we wrapped up our look at Madison’s notes on the Constitutional Convention. We touched on many subjects, but centered on one particular issue that illumines both the glory and the problems of the heritage of that august assembly.

As the constitution neared completion, the delegates debated how the document would be received by the public. What would make the Constitution the law of the land? Should the states ratify it through their state legislatures, or should a general, national plebisite of the “people” make the decision?

The issue seems mundane, but at its root lay certain key ideas and problems.

If the states ratified the Constitution, it might seem that the states had superiority over the federal government the document created. Charlemagne, for example objected to being crowned “Holy Roman Emperor” by Pope Leo III (he would crown his son and successor before the Church had a chance), much in the same way that Napoleon refused to allow Pope Pius VII to lay the imperial crown on his head. He who crowns the king has authority over the king. If the states gave the Constitution authority, they implicitly would hold supreme power.

The problem with this approach was that the delegates wanted to create a document that significantly increased the power of the federal government relative to the states. A handful of delegates at the convention wanted to get rid of states altogether.

Another option involved a national ballot referendum and a direct appeal to the people. Bypassing the state legislatures would help emphasize the new power base of the national government. It would exist not on the foundation of the states, but on the people/”nation” at large.* So far, so good. But most of the delegates gravely distrusted the wisdom of “the people,” and feared putting so much power in the hands of those they felt could be easily manipulated.^ So they had to flip a coin, basically, between Scylla and Charybdis.

As the delegates debated an even deeper issue arose. Why were they in Philadelphia in the first place? On whose authority? “If we exist under the authority of the Articles of Confederation,” they might have thought, “then we must give ratifying authority to the states. But if we exist under the Articles, then we must abide by the key principle of the Articles and not make any new changes without the unanimous consent of all the states.” But with the decisions they already had made unanimous consent had been rare. Besides, some states did not have any delegates at the Convention at all. Clearly then, they could not be proceeding under the Articles of Confederation or they would have to rework almost everything.

“But if we are not here under the authority of the Articles,” then who or what gives us the authority to make any decisions? Will the new government get formed under our own assumed authority, or the authority of ‘the people?’ Are we just making this up as we go?” I do wonder if the delegates felt themselves at the edge of a great precipice, or on the threshold of a dark and mysterious house, with little idea of what might come next.

One debate surrounding the American Revolution is the question as to whether or not the founders were “radicals” or “conservatives.” Some scholars (like Edmund Burke) see the Americans as conservatives trying to preserve traditional ideas of government. In this view it was the English, not the Americans, who were the real “radicals.” As much as I hate to disagree with Burke, I think the vast bulk of the evidence suggests that the founders were the radicals (historians like Bernard Bailyn and Christopher Ferrara agree) and changed the very basis of modern governance.

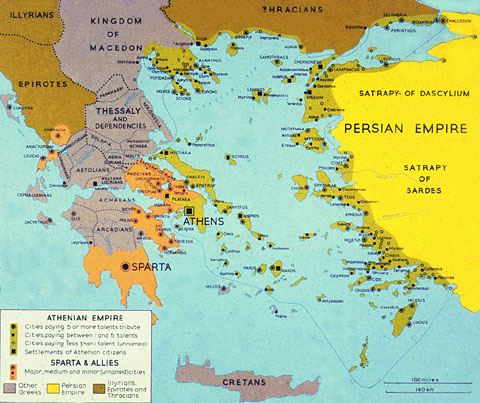

Back in ancient times kings derived their authority from the gods. Though the Greeks may have departed from this briefly in the golden age of their democracy, their philosophers rooted all legitimate authority in notions of Truth/God (Plato), or the Natural Law (Aristotle). The Romans had a republic, yes, but their political offices often had religious overtones and the early Romans at least did everything with reference to the gods. In Christendom, kings clearly believed they derived their authority ultimately from God, and that the state should reflect in some ways God’s kingdom and His governance on Earth.

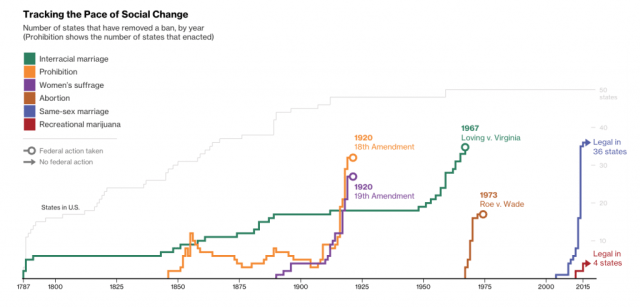

The founders made no such assertions. They formed a government rooted in Locke’s theory of the “consent of the governed” forming the basis of all legitimate power. This gave the founders a great deal of freedom to improvise, but also created difficult dilemmas. How should the “consent of the governed” be measured? What if what the governed consent to changes over time? Without a clear and fixed point of reference, notions of authority, legitimacy, and morality inevitably would shift over time.

The founders should receive praise, I think, for creating a thoughtful system of government that did well in preventing abuses of power (relatively speaking) and allowed for a healthy tension of unity and diversity within the country. But even some of those present in Philadelphia in 1787 had a premonition that had little claim to authority beyond their own ideas. Some made reference to history with their political ideas, others to experience. But very few sought to root their thoughts in any authority beyond that. The ripples effects of this certainly linger with us today. What gives the Constitution authority is that we agree it has authority — we consent to its authority. But as that authority has its roots in day-to-day consent, so too the meaning of our consent will change over time. Hence, we decide Constitutional question by majority vote. We may lament this, but the Constitution itself has little more to offer us.

Blessings,

Dave

*Patrick Henry objected to the Constitution because he recognized this shift of power in the first three words, “We the people . . . ” He recognized the diminished role states would play in the new government.

^Reading Madison’s notes, students were routinely surprised to see the attitude of most delegates towards “the people.” A great question to ask might be, “How democratic is the Constitution really?”