Greetings,

Category Archives: American History

Bored Borders

I know very little about the great civilizations of Meso-America, so I was intrigued to at least skim through Tales of the Plumed Serpent: Aztec, Inca, and Mayan Myths. I have long thought that the myths and folkore of a civilization form one of the best entry points for the novice. Each of these cultures had remarkable achievements in nearly all marks of what we generally call “civilization.” Their architecture and engineering alone can rival that of Egypt and Rome.

Of course, studying these cultures comes with the big elephant in the room of human sacrifice. We associate this primarily with the Aztecs, and they may have practiced this on a larger scale than other civilizations in the region. But the Incas and Mayas both offered human victims on their altars. Some of their myths, as we might expect, help lay the foundation for such terrors.

I understand that any editor should have a light touch in such a collection. One wants to let the stories speak for themselves. And yet, the extreme desire to stay “neutral” in itself reflects a certain worldview. On page 87 the editor includes a section on human sacrifice, and writes,

Further to the south, the Incas practiced human sacrifice too. One notable and particularly poignant custom was the rite of “capacocha,” in which the victims were usually children. After going to Cuzco to be blessed by the Inca priests, the “capacochas” returned home in procession along straight routes called “ceques.” Here they were either buried alive in subterranean tombs or killed with clubs and their bodies left on mountaintops.

The word “poignant” seems dramatically inappropriate for such a description.

True, the Spanish found much to admire about the religious zeal of the Aztecs, for example. Perhaps some of the victims volunteered out of a genuine sense of zeal. But surely we should not assume that children “volunteered.” Surely we have not so lost our way that we cannot call children being buried alive “horrifying,” or at the very least, “tragic.”

I can’t help but surmise that if the Greeks or Romans practiced this, different words would have been chosen to describe them. For Meso-American cultures suffered under European colonialism, and this seems to mean that, having been granted victim status, they can do no historical wrong.* But the situation has much more complexity than this.

NOVA’s documentary about the deciphering of the Mayan language called Cracking the Mayan Code has many things to recommend it. But it begins with the obligatory castigation of Spanish priests destroying the manuscripts of the Mayans, who clearly did so out of “ignorance” of the Mayans and contempt for their culture. At no point are we encouraged to consider whether or not Mayan culture should remain entirely entact. One can find things to admire about the ante-bellum South, for example, but slavery had to go, and removing slavery might mean altering other aspects of ante-bellum culture. However messy this might get, I would be surprised if many in academia object to the damage done to southern culture in the effort to destroy slavery.

The Spanish priests perhaps prescribed a stern remedy for the Mayans by destroying their manuscripts, but we should at least consider:

- Did the priests believe that the foundations of human sacrifice needed eradicated?

- Did the manuscripts provide a religious foundation for human sacrifice?

- Should the missionaries attempt to end human sacrifice? If destroying the manuscripts helped accomplish this, should we see this as worth the cost of the loss of knowledge about Mayan language and history?

- Did the priests see themselves as part of the “lineage” of the prophet Elijah, who proposed a contest with the prophets of Baal (whose worship also occasionally involved human sacrifice), or St. Boniface, who chopped down the oak of Thor? If so, was this connection justified?

We must at least entertain these questions, but on many campuses this would not be easy to do.

Acquiring such nimble minds would be entirely necessary for reading Henry of Livonia’s chronicle of Baltic Crusades in the 13th century. A brief synopsis of his account is almost impossible. Some converted under early missionary work, and the church sent other clergy to help establish churches in the area. Some fought against the church by attacking and murdering clergy and other Christians, others reneged on their conversions, making things even messier and more confusing. And so it went. The introduction to his text reveals that in the 19th century, German scholars revered Bishop Berthold for his tenacious will in establishing the church in the area. The editors rightly raise some eyebrows at this, for no one who reads the text would admire the bishop for his love, understanding, and perspicacious wisdom, whatever other qualities he possessed. And of course we know what the early 20th century had in store for Germany. But as one might imagine, today the editors see only the destruction of culture and cruelty, wildly swinging the pendulum of analysis. Even a cursory reading of Henry shows his appreciation for local cultures, but also the tension that comes when we encounter destructive pagan cultural practices. We should cultivate the boundaries of our minds so that we can make judgments without rushing to stark ideological conclusions that have no sympathy for one side or the other. When the introduction to Henry of Livonia reveals is that this is not a strictly modern problem, and that may be of some comfort.

As the center of our own culture erodes the our physical and mental boundaries inevitably become more porous. Douglas Murray tackles this in The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam. Murray writes with conviction but this is not a screed. He at least appreciates the tension between maintaining a cohesive identity as a culture and helping those in desperate situations. If we cannot recognize this tension debating the issues will go nowhere.

The problem Europe experiences over these issues, however, runs deeper than the plight of the desperate. First of all, many of those who migrate appear not to be desperate refugees but young Moslem men looking for greater economic opportunity. That, of course, does not make them bad people by any definition, but it should alter the debate somewhat. Murray believes that European leadership has distanced itself from their people. Their willingness to allow more migrants significantly outdistances the desires of most voters. But to the extent that this is true, the problem can easily get fixed in subsequent elections.

The immigration issue exposes deeper rifts in beliefs about democratic practice. Those on the right and left both believe in democracy. Conservatives tend to see democracy as somewhat fragile. Democracy can work only with healthy institutions and an instinctive level of trust between people that comes from shared values and a shared culture. If your candidate loses the election, you can shrug your shoulders and try next time, knowing that, whatever your differences on tax policy or budget allocations, you know that nothing substantive about your life will change. The moment you stop believing this about other candidates from other political parties, fear may drive you to do more than simply shrug your shoulders

Many liberals these days** (so it seems to me–I am a conservative, so forgive and feel free to correct any misrepresentation), believe that democracy is primarily a powerful idea, not a complex practice or culture. Ideas can transfer easily, thoughts have no borders. So, democracy requires little more than belief in “freedom” or “equality,” and participation–“make sure you get out and vote”–to work successfully.

Conservatives might balk at the prospects of bringing in millions of mostly young men who neither share your religion, your cultural values, your shared democratic practice, and no history or context for understanding the issues. If recent immigration policies tell us much, liberals tend to believe that this poses no fundamental problem to continuing our democratic practice.

For Murray, the deeper problems involve a profound spiritual malaise, a great crisis of confidence Europeans feel about their own institutions and culture.

One can argue that civilizations should function much as individual people function, and have the capacity to exercise humility and repentance, though this is dicey and comes with many complications. But granting this and leaving the question aside, one could argue that western civilization has much to repent of, such as imperialism, slavery, etc. Of course western civilization is hardly alone in committing such sins, but we can only repent of our sins, and not those of others. But as St. Paul writes in 2 Corinthians, and St. Peter and Judas demonstrate, there is a godly sorrow that leads to life, and a sorrow that leads to death.

Much of Murray’s book indicates that large swaths of the political class of Europe may wish for something akin to an atoning annhiliation of their culture–akin to Van Gogh cutting off his ear. Recently an op-ed piece from Todd May in no less than the New York Times argued that for the good of the Earth, humanity as a whole should make itself extinct. But most on the far-left only desire this of western culture. Consider a very small smattering of examples:

- Sweden’s PM Frederic Steinfeld stating that, “only barbarism is genuinely Swedish.”

- The extreme reluctance of law enforcement agencies to publish the ethno-national information of the accused when they come from Moslem areas, lest they (so I suppose) seem racist.

- In the aftermath of the coordinated sexual assaults in Cologne, Germany on New Years Eve 2015, the response of some was to give instructions to women on how they should behave around young migrant men. What makes this troubling to me is the assertion that Germans should adjust to the behviors and culture of their guests, and not vice-versa (no one would, or should, make the equal assertion that Germans abroad should expect their hosts to conform to German cultural norms).

- The failure of states to aggressively try and curb the rise of anti-semitism in areas of high Moslem concentrations.

All of his examples illustrate Murray’s main theme of internal cultural immolation,^ a drastic diagnosis, but one that seems apt.

The problem of borders often raises its head often in history. On the one hand borders strike us as entirely artificial. Nothing in the nature of the universe would have it that America occupy a certain amount of space with a certain amount of prosperity. If borders be artificial, no good reason exists to prevent anyone from moving anywhere.

But, on the other hand, borders must exist, for without them we would have no way to order our lives politically or economically. Borders lack the legitimacy of natural law they have a relationship to natural law. I think national boundaries are akin to our relationship with food. There is nothing that says we must have either chicken, pizza, or salad, but we must eat some kind of food to survive. Some form of national and cultural boundaries, then, seems necessary to our existence.

The borders in our mind are more crucial. Maintaining distinctions in creation is one of the hallmarks of Genesis 1. Light is not darkness, morning is not evening, trees are not fish, and men are not women. As we review Incan mythology, we have to say that burying children alive is worse than being merely “poignant.” We must not assume that a pagan culture is by definition “oppressed” when they come into contact with the Christian west. We have to have conversations about emotionally difficult subjects like immigration. If the viral malaise that stymies this bores its way into other borders of our mind, eroding the entirety of our mental structure, so our cultural structures. will follow suit. And because chaos has no differentiation, the sameness of all things can get boring–as well as dangerous.

Dave

*Without excusing the subsequent actions of the Spanish and Portuguese in the least–actions that many contemporary Europeans themselves criticized–one must remember, for example, that Cortez had a great deal of help in bringing down the Aztecs. Many other local tribes rallied around him, and perhaps they did so at least in part because they wanted to protect themselves from the Aztecs sacrificing them on their altars.

**Some could also lump the neo-conservatives of the early 2000’s into this group, so perhaps this is not exclusively a liberal belief.^I will go on record as saying that I agree with Murray that Europe is a undergoing a kind of cultural suicide, but I don’t see this necessarily as a recent phenomena of the last 15-20 years. In other words, it’s not primarily the fault of too much immigration. Perhaps this is merely a symptom. Rather, Europe began this process many decades or perhaps centuries ago. Europe as we know it had its foundations with the Church, and has painstakingly eroded that foundation. Without this, the edifice built upon this now non-existent foundation will have to collapse.

11th Grade: Civil War Voices

Greetings,

This week, I include without comment a handout I gave the students which includes thoughts on both sides about slavery and secession. Many thanks,

Dave

Thoughts on Secession

Pro-Secession Quotes

No one can now be deluded that the Black Republican party is a moderate party. It is in fact a revolutionary party. – the ‘New Orleans Delta’ newspaper

[Secession] is a revolution of the most intense character, and can no more be checked by human effort than a prairie fire by a gardeners water pot. – Sen. Benjamin, Louisiana

Secession is an act of revolution, a mighty political revolution which will result in putting the Confederate states among the independent nations of the earth.’ – Vicksburg mayor

I never believed the Constitution recognized the right of secession. I took up arms upon a broader ground–the right of revolution. We were wronged. Our properties and liberties were about to be taken from us. – Confederate Officer

Were not the men of 1776 secessionists? – Alabama delegate

If we remain in the union, we will be deprived of that which our forefathers fought for in the revolution. – Florida delegate

Will you be slaves or independent? Will you consent to being robbed of your property, or will you strike bravely for liberty, property, honor and life? – J. Davis

We left the union to save ourselves from a revolution–a revolution to make property in slaves so insecure as to be comparatively worthless. – J. Davis

[Our founders were wrong] if they meant to include Negroes in the phrase ‘all men.’ Our government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its cornerstone rests upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery is his natural and normal condition. ‘ Alexander Stephens, VP of the Confederacy

I am fighting for the rights of mankind–fighting for all we in the South hold dear. – Confederate soldier

We cannot wait for a ‘overt act’ by Lincoln. If I find a coiled rattlesnake in my path, do I wait for his ‘overt act’ or do I smite him in his coil?’ – Alabama editor

If you are tame enough to submit, abolitionist preachers will descend to consummate the marriage of your daughters to black husbands. Will you submit to have our wives and daughters choose between death and gratifying the hellish lust of the negro? Better ten thousand deaths than submission to Black Republicanism. – Rev. J. Furman

Democratic liberty exists because we have black slaves, [whose presence] promotes the equality of the free. Freedom is not possible without slavery. – Richmond Enquirer, editorial

When secession is inaugurated in the South, we mean to do a little of the same business here and cut loose from the fanatics of New England and the North generally, including most of our own state. – New York lawyer, speaking in support of Mayor Fernando Wood, who wanted New York City to become independent.

An Interesting Quote that falls into Neither Camp Directly

Secession is nothing but revolution. The framers of our constitution never exhausted so much labor, wisdom, and forbearance in its formation, and surrounded it with so many guards and securities, if it was intended to be broken by any member of the Confederacy at will. Still, a Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets, and in which strife and civil war are to take the place of brotherly love and kindness, has no charm for me. If the Union is dissolved, the government disrupted, I shall return to my native state and share the miseries of my people. Save in her defense, I will draw my sword no more. — Robert E. Lee

Anti-Secession Quotes

The great revolution has actually taken place. The country has once and for all thrown off the domination of the slaveholders. – Charles Francis Adams

The founders fought to establish the rights of man and principles of general humanity. The South rebels not in the interest of general humanity, but of domestic despotism. Their motto is not liberty but slavery. – W. Cullen Bryant

The framers never intended to implant in its bosom the seeds of its own destruction, nor were the guilty of providing for its own dissolution. [If secession stands] our 33 states may resolve themselves into as many petty, jarring, and hostile republics. By such dread catastrophe the hopes of freedom throughout the world would be destroyed. – James Buchannan

I would hang every man higher than Haman who would attempt to break up the Union by resistance to its laws. – Stephen Douglas

I hold that the election of any man on earth by the American people, according to the Constitution, is no justification for breaking up the government. – Stephen Douglas, commenting on the states that seceded after Lincoln’s election, but before he took office.

State sovereignty is a sophism. The Union is older than any of the states, and in fact created them as states. Having never been states, either in substance or name, outside the Union, whence this magical omnipotence of State rights, asserting a claim of power to destroy the Union itself? – A. Lincoln

Revolution is a moral right, when exercised for a morally just cause. When exercised without such cause revolution is no right, but a wicked exercise of physical power. The event that precipitated secession was the election of a president by a constitutional majority. We must settle this question now, whether in a free government the minority have the right to break up the government whenever they choose. – A. Lincoln

Disunion by armed force is treason, and treason must be put down at all hazard. The laws of the United States must be executed–the President has no discretionary power of the subject–his duty is emphatically pronounced in the Constitution. – Illinois State Journal.

Other Thoughts

Slavery is the divinely appointed condition for the highest good of the slave – ‘Richmond Whig’

The free labor system educates all alike, and by opening all fields of employment to all classes of men. It brings the highest possible activity all the physical and mental energies of man. — William Seward, Governor of New York

Free society! We sicken at the name. What is it but a conglomeration of greasy mechanics, filthy operatives, and moon struck theorists? They are hardly fit for association with any Southern gentlemen’s body servant. – ‘Muscogee Messenger’

Slavery is the natural and normal condition of society. The situation in the North is abnormal. To give equality of rights is but giving the strong license to protect the weak, for capital exercises a more perfect compulsion than human masters over slaves, for free laborers must work or starve, and slaves are fed whether they work or not. – G. Fitzhugh, Virginia politician

Slavery is destined, as it began in blood, so to end. – Abolitionist Thomas Higginson

Slavery lies at the root of all the shame, poverty, ignorance, and imbecility of the South. Slavery is against education. – Hinton Helper, North Carolina author

Relic

The Introduction to Relic opens this way:

American government is dysfunctional . . . . As a decision-maker Congress is inexcusably bad . . . utterly incapable of taking responsible, effective action . . .

So why is this happening? The common view is that Congress’ problems are due to the polarization of the [political] parties over the last few decades. By this rendering, if the nation could move towards a more moderate brand of politics–say by reforming primary elections or campaign finance–Congress could get back to the way it functioned in the good old days when it (allegedly) did a fine job of making public policy.

But this isn’t so. . . . The brute reality is that the good old days were not good. . . . Congress’ fundamental inadequacies are not due to polarization. Nor are they of recent vintage. Congress is irresponsible largely because it is wired to be that way–and it’s wiring is due to Constitutional design.

[Congress’] pathologies are not really of it’s own making. They are rooted in the Constitution, and it is the Constitution that is the fundamental problem.

I have concerns over the growth of presidential power in the last few generations, but . . . I love it  when writers undertake such magnificent and almost dashing glove-slaps to our received wisdom. Authors William Howell and Terry Moe teach at the University of Chicago and Stanford respectively, so this is not a talk-show rant. They write with an apolitical bent for the most part and take a broad view. They focus on clarity and concision and don’t try and dazzle us with their erudition.

when writers undertake such magnificent and almost dashing glove-slaps to our received wisdom. Authors William Howell and Terry Moe teach at the University of Chicago and Stanford respectively, so this is not a talk-show rant. They write with an apolitical bent for the most part and take a broad view. They focus on clarity and concision and don’t try and dazzle us with their erudition.

I don’t think I agree with them, but I admire their efforts. We need more books with these strengths.

Their basic argument runs as follows:

Before the Revolutionary War each colony acted almost entirely independently of one another. No one had any idea of a “United States of America.” During the war we created the Articles of Confederation, which, while it created a national government, made it exceedingly weak.

This then, is their first main point. Yes, the Constitution created a stronger national government–but not that strong. We have to understand the Constitution’s grant of executive power not in a vacuum but in relation to the Articles of Confederation. The Constitution still allowed for states to have the pre-eminent place in people’s hearts.*

The design of our federal government reflects this by giving nearly all the most important powers to Congress. This in turn makes it very difficult to enact national policy. This was not a mistake. This is the exact intention of most of the founders (though not all, such as Alexander Hamilton, who argued for a much stronger executive at the Constitutional Convention).

When we manage to create a national policy, such policies get diluted, confusing, and sometimes absurd because of the fact that all laws have to come through Congress. Everyone wants their piece of pork, everyone needs something to crow about. The confusion of many laws, and the expense needed to enforce them, weakens government, expands bureaucracy, and lowers quality of life. Again, the authors don’t blame Congress for this. Our representatives have job of representing their districts, not the national interest.

The authors argue that Congress has never solved a national problem. It has either taken either national emergencies (like war, disasters, etc.) or unusually shrewd or charismatic presidents to get Congress to move. They concede that perhaps our form of government worked in the pre-industrial era when towns remained largely isolated from one another (though Congress certainly could not solve the slavery issue, the biggest contributor to the Civil War). But the Industrial Revolution created a new country that drew the states much closer together. We now think of ourselves as “Americans” and need national policies on a consistent basis. Again, we should not say that Congress will not solve them. Congress cannot solve them, just as pigs can’t fly. We have, in fact, many problems on the horizon that have existed for decades that Congress will never solve, such as Social Security reform, the tax code, the national debt, and so on. And while the American Revolution inspired a variety of democratic movements across the globe, no one has copied our system of government.** This should tell us something.

Their solution mirrors the simplicity of their writing. They know that rewriting the Constitution is impossible, and officially amending it very difficult. Instead they seek “fast-track” authority for certain kinds of legislation.

Lest we deride their analysis as overblown, the authors point out that we already recognize the foolishness of our constitutional design with international treaties and trade agreements. We give the president power to negotiate such agreements without congressional interference. Presidents then can present them to Congress for a simple “yes”/”no” vote.

The authors propose that we simply allow presidents to submit legislation to Congress involving national policy for this kind of yes/no vote. No pork, no earmarks, no preferments, no deals. Congress needs to keep its diseased hands away from issues like the national debt, health-care, and national defense. If such laws passed they would have the clarity and unity needed for effective policy.

That’s it. No fuss, no muss. It preserves the Constitutional role for Congress and merely expands slightly the powers of the executive.

The authors write with great force, but part of me wonders, has it really been so bad? Sure, the separation of powers brings problems, but America has a top notch military, technological innovation, a leading economy, a high standard of living, and so on. Yes, we have difficult social issues, but we also have much greater challenges in this regard than most other nations. Ok, we have rocky outcroppings in many parts of our history, but so too do other modern democracies.

It’s hard to disagree, however, that Congress annoys us like no other branch of government.

As much as I enjoyed the book, the authors missed the root question. Of course their suggestion would make government more efficient and policy more workable. The authors argue that their proposed alteration involves no real philosophical issue. We simply need something that works. Wanting a dishwasher that works, for example, need not involve politics, philosophy, or theology.

Part of my hesitation to jump in with the authors, however, lies with just these concerns. We should concern ourselves with more than whether or not something works. We should consider the implications of increased executive power. Many of the founders were philosophers as well as practical politicians. We owe it to our past to at least consider such things before going far beyond what they intended.

Dave

*I wonder if the authors would have agreed with Napoleon’s assessment of America while in exile on St. Helena in 1816. Napoleon foresaw the Civil War, among other things. He commented,

What is needed for national defense? Unity and permanence in government. America remains united for now due to their common interest of their emancipation from the English crown. But their existence as a great nation was impeded by their federal constitution. A dissonance exists between northern and southern states which reflects on the weakness of the federal principle. Either the national government will be strengthened by conquest, or else national unity will be broken by local interests and commercial rivalries.

**This is a good point, but America also had a unique historical situation that preceded their revolution.

The Analogy Gap

I remember that back in my day, we had multiple sections of analogies on the SAT. I always thought they were fun, but alas, analogies are no longer part of the test. Apparently different reasons exist as to their absence, ranging from cultural bias to not wanting the test to seem too “tricky.” I care little for standardized tests so I wouldn’t argue the point too strongly, but I think any look around at our discourse, where everyone who sneezes wrongly gets compared to Hitler, shows that we need more rigorous analogical thinking in our lives.

Of course analogies can be tricky, but making sense of reality requires them, so we need good ones and we need to distinguish good ones from bad. As long as we know that using a three-leaf clover to describe the Trinity works in some ways and fails in others, we can benefit from the illustration. But using a car, a cigarette, and an oven as a replacement analogy can’t help anyone, despite the fact that all three can sometimes produce smoke.

MIT professor Vaclav Smil specializes in the study of energy, but he has a hobby of reading Roman history. In the wake of our post 9/11 military ventures, and especially after things in Iraq began to go south, we saw many academics proclaiming the demise of the American “empire,” with comparisons to the fate of Rome everywhere across the media landscape. Smil smelled a rat, and wrote Why America is not a New Rome to counter this wave. I wish he put more thought into his title, but it points to the straightforward approach of his work. He brings the discipline of a scientist to the fog of blogs and talking heads.

post 9/11 military ventures, and especially after things in Iraq began to go south, we saw many academics proclaiming the demise of the American “empire,” with comparisons to the fate of Rome everywhere across the media landscape. Smil smelled a rat, and wrote Why America is not a New Rome to counter this wave. I wish he put more thought into his title, but it points to the straightforward approach of his work. He brings the discipline of a scientist to the fog of blogs and talking heads.

The question is one of analogy–how alike are the American and Roman experiences?

The comparisons should not surprise us, and have some basis in fact. Our founders modeled our constitution on Rome’s. Our early years resemble the heyday of the aristocratically oriented Roman Republic governed primarily by a strong Senate. Since the Industrial Revolution, and especially since the Great Depression, we have witnessed the continual growth of executive power until now Congress has nearly reached rubber-stamp status, akin to the senate in Rome under the emperors.

Briefly, then, the case for strong links between America and Rome:

- After 1989, America had no real military or economic competitor, just as Rome had no real competition in its sphere of influence after the 2nd Punic War

- America has more than 200 overseas bases and can put its military in action most anywhere in the globe much faster than anyone else, just as Rome could move with its road system throughout its empire.

- The world economy is controlled through New York, and Washington sets the basic rules of this economy, just as Rome did so for centuries in its era.

- At the same time, both societies experienced drains on the real power of their economy through foolish military ventures and lack of stable monetary policy.

- Both societies developed professional militaries that have grown increasingly distant from the general public

- Both societies exercised considerable soft power through their cultural exports

- The population of both societies seemed driven by distraction and entertainment. Some point out strong connections between the gladiatorial games and our love for (American) football.

- A loss of cultural glue across large geography means that trust and the ability to suffer together both decrease. Hence, both societies would “buy off” the population with bread, buyouts, stimulus packages, etc.

- Some even went so far as to say that both civilizations had a, “common obsession with central heating and plumbing.”

Stated this way some connections seem strong, but Smil doesn’t buy it.

First we can consider the concept of “empire.” Some understand that if America has an empire, it is “informal,” and “an empire without an emperor.” Smil argues that some concepts of empire are so vague as to be meaningless, and pushes for a very specific definition:

Empire means political control exercised by one organized political unit over another unit separate from it and alien to it. Its essential core is political: the possession of final authority by one entity over the vital political decisions of another.

With this definition in place we should consider if America ever exercised imperial ambitions. Perhaps one could begin with the Mexican War of 1846, or perhaps earlier with the Indian wars that made the Northwest Territories into Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. With our various conflicts on the continent we did not so much seek to control ‘alien’ peoples as much as we sought to move in and displace them. Perhaps one could argue that the Spanish-American War made us an imperial power, but even then, we gave Cuba independence immediately and the Philippines got their independence right after W.W. II. Smil spends a lot of time on this rather technical argument over what exactly constitutes an empire. He has some good points to make, but only stylistically. The real question, I think, involves how much power the U.S. has vis a vis the rest of the world.

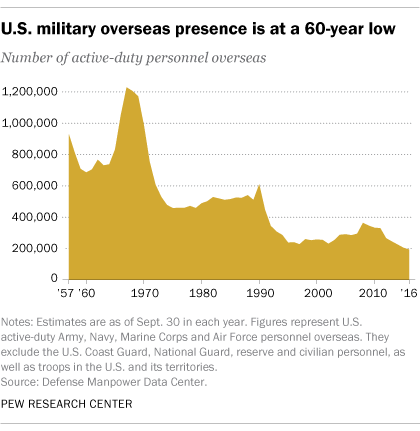

Here Smil gets more interesting and convincing. He cites a variety of data to show that American power, or at least our relative share of power (in political, economic, and military terms), has actually declined dramatically since the end of W.W. II. Our global share of economic output has dropped by at least 1/3 since 1945, with continuing trade deficits largely due to reliance on foreign energy. We send much less of our military abroad than we used to. True, we have hundreds of military bases all over the world, but less than 20 of them have more than 1000 troops. President Eisenhower served as our top military commander in our most glorious and successful war. Yet he denounced the “Military-Industrial Complex in his farewell address. One cannot even conceive of any Roman ever doing any such thing. Empires do not act this way.

Smil agrees that we might call the U.S. a “hegemonic” power and not an empire. But . . . he argues that we are either a weak hegemon or a benign one. Castro ruled Cuba for decades and all agreed he posed a potential threat to our well being, yet we could do nothing to stop him. Similarly, we could not get rid of North Korea or beat North Vietnam. Smil continues,

Germany was defeated by the United States in a protracted war that cost more than 180,000 lives, subsequently received America’s generous financial aid to resurrect its formidable economic potential, and is home to more than 60,000 U.S. troops. Yet when its foreign minister was asked to join the Iraq War coalition, he simply told the U.S. Secretary of Defense, “Sorry, you haven’t convinced me,” and there the matter ended.

No less tellingly, the Turkish government (with NATO’s second largest standing army and after decades of a close relationship with the U.S.), forbade US forces to use its territory for the invasion of Iraq, a move that complicated the drive to Baghdad and undoubtedly prolonged the campaign. America in a time of war could not even count on two of its closer allies, but there was no retaliation, no hint of indirect punishment, such as economic sanctions or suspension of certain relations. One could cite many other such instances . . . both illustrating America’s ineffective hegemony and non-imperial behavior.

With a proliferation of graphs and paragraphs like these, Smil makes a good case that America exercises far less power than its critics at home and abroad surmise. Smil’s book is not brilliant, but he writes with a concision and clarity that cannot but convince the reader.

Or perhaps, very nearly convince. American political culture struggles for coherence at the moment, but we have experienced times in our past very much like this before. We have a disconnect between cultural elites and everyday people, but as Smil points out, this happens in almost every advanced civilization. Economic inequality is a problem, but again, Smil shows how this tends to happen in many advanced economies, and in any case, our inequality now is not nearly as great as it was in the late 19th century. By these measures we are no more an empire, or no more in decline, than other countries with power at different times. The analogy is too thin to make anything of.

But . . . perhaps the strongest point of comparison lies elsewhere. Toynbee argued that the military and economic problems Rome experienced in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD had their roots in the spiritual detachment of stoicism. In a similar vein, Eric Voegelin wrote frequently that global power and global influence (of which the U.S. certainly has in some measure) easily leads to a gnostic view of the created order, which again inspires a detachment and loss of engagement.

Perhaps this should be our biggest concern. We have recently legalized pot, the new drug of choice (in contrast to stimulants like cocaine of 30-40 years ago). The digital revolution allows us to entertain ourselves with our screens and enter fantasy lands alone in our rooms. Recently the Caspar mattress company founded a line of stores dedicated to napping as an art form. It may be a good thing not to have a political, military, or other such analogous connections to Rome. Here’s hoping that our growing sense of detachment is not in fact the strongest point of comparison between us.

Dave

A House Swept Clean

Richard Rorty’s America had a wonderful run, even if it was short lived.

I well remember my senior year of high school in 1990-91. For the first few months of school Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait had pride of place in our minds. We had furious debates as to the rightness or wrongness of our presence in the Mid-East. As military action looked more imminent, the arguments got more heated. I filled out my draft service card. Some thought the war could take years and become a dreaded “quagmire.”

The fighting actually started and a hush fell over the debates. And then, just as quickly, the fighting ceased. The ground war took no more than a week. We sat stunned for a moment, then, elation. Talk of world affairs ceased immediately. We all shifted into thinking about college, planning out our lives, and so on. The Soviet Empire had crumbled. What was left but Kant’s dream of perpetual peace and George Bush’s “New World Order?”

The end of the Cold War brought about the end of modernism in the mainstream and a shift towards the postmodern individualistic ethos. Professors like Richard Rorty from the University of Virginia rode the wave. Rorty hit the sweet spot. In contrast to some academics, he championed the American project and American exceptionalism, which went well with our post Cold-War confidence. He also gave free vent philosophically to our desire to maximize our individual idea of happiness as far as we wanted. No one grand narrative need control us. In fact, for Rorty the 1990’s allowed for America to truly fulfill her mission as a kind of blank slate for autonomous individuals. All could achieve happiness, none need worry about “Civilization” or religion.

Ah, the 1990’s. Good times, good times.

Peter Augustine Lawler tackles the thorny problem of the nature of the American Enterprise in his Aliens in America: The Strange Truth about our Souls. In his work Lawler examines the various attempts to craft a secular paradise in America from Thomas Jefferson down to Richard Rorty and Francis Fukuyama. Lawler agrees with many of the intellectuals he examines that America has essentially been about creating a republic of happy and secular individuals. In this way he mostly sides with the liberal interpretation of America vs. the religious and conservative interpretation. But he parts with them ultimately, stating that this dream, though seemingly close to realization at certain points in time, can never come to fruition.

Aliens in America: The Strange Truth about our Souls. In his work Lawler examines the various attempts to craft a secular paradise in America from Thomas Jefferson down to Richard Rorty and Francis Fukuyama. Lawler agrees with many of the intellectuals he examines that America has essentially been about creating a republic of happy and secular individuals. In this way he mostly sides with the liberal interpretation of America vs. the religious and conservative interpretation. But he parts with them ultimately, stating that this dream, though seemingly close to realization at certain points in time, can never come to fruition.

Lawler published this originally just after 9/11. We might think that he would point to the terrorist attacks as destroying the liberal dream. True, he seems to argue, 9/11 did perhaps hasten the end of the most recent attempt at secular paradise, but it would have ended at some point in any case. To see this one need not exhaustively examine the thought of various thinkers over time (this indeed got old for me, as each thinker-guy in the book ran together in my brain). Rather, it was when Lawler looks to two of the most perceptive critics of America in Tocqueville and Walker Percy, that his own ideas make sense.

Most know the basics of Alexis de Tocqueville’s monumental Democracy in America:

- He came from an aristocratic background

- He came to investigate democracy, seeing it as the wave of the future

- He offered important criticisms of democratic practice, while giving it the nod in the end over the aristocratic past.

One could say a great deal about this work. Lawler focuses on an oft-overlooked observation of Tocqueville’s about aristocracy. Aristocracy has its flaws, but in giving people a definitive place and a definitive role they give people something to do. Aristocratic societies come with “meaning included” in the packaging. This goes not just for the elite. Even Odysseus’ dog knew he had purpose.

Tocqueville praises the machinery of democracy for making everyone equal to all. Everyone believes that this means they have worth as an individual, and they have reason for this belief. This rational pursuit of self-interest then creates a nation of those who create peace by a kind of selfishness, just as markets create equilibrium via constant competition. But even in the late 1830’s Tocqueville saw what we could not–that equality would actually create a large amorphous mass in which few of us would know where we stand. We are told to be whatever we wish, but more than a few of us respond with, “And what might that be?”*

Rorty and others no doubt praise this possibility as exactly the meaning of America, one that should persist into time immemorial.

History gives witness to others of like mind and goal to Rorty. Rorty rejected much of modernity and the Enlightenment, but he shared with Gibbon, Voltaire, Hume, and others of that time a belief that calm, rational self-interest could conquer the ills of “barbarism and religion”–a phrase used by Gibbon in describing the fall of Rome in his magnum opus, writing that, “I have described the triumph of barbarism and religion.” For him, Rome had reached its zenith with the rule of the humane, tolerant, religiously skeptical and urbane Antonine Emperors (A.D. 96-180).

Like Edward Gibbon, historian Arnold Toynbee sought for universals amongst particulars in his multi-volume A Study of History, and so perhaps this helps explain why one particular quote of Gibbon’s fascinated Toynbee, as he uses the quote several times across his twelve volume work. In 1781 Gibbon wrote that,

In War the European forces exercised themselves in temperate and indecisive contests. The Balance of Power will continue to fluctuate, and the prosperity of our own or neighboring kingdoms may be alternately exalted or depressed; but these partial events cannot injure our general state of happiness, the system of arts, laws, and manners, which so advantageously distinguish, above the rest of Mankind, the Europeans and their colonists.

With the mild peace settlement after America’s victory in the Revolutionary War, Gibbon looked justified in his assumption. It seemed that Europe’s house was swept clean of the various bothers of the religious wars. It seemed that a paradise of calm rationality awaited them.

But 10 years after his utterance, the illusion disappeared utterly in France’s revolution (a nation that drunk deeply from the well of Enlightenment), engulfing Europe in 20 years of war that left perhaps three million dead.

Hugh Trevor-Roper writes in his History and Enlightenment about Gibbon that

. . . Gibbon gave a confident answer to the problems of his time. Since progress depended on science, and since science and the useful arts were irreversible in a world of free competition and inquiry, and since Europe, unlike the Roman Empire, was a plural society where competition could not be stifled by a single, repressive, centralized figure, a reversion to barbarism was unthinkable. Gibbon wrote that, “the essential engine of progress having been distributed over the globe, it can never be lost. We may therefore acquiesce in the pleasing conclusion that every age of the world has increased, and still increases, the real happiness, knowledge, and virtue of the human race.”

I think Gibbon’s quote above fascinated Toynbee because in Gibbon he saw of man of great intellect, good intention, and broad vision completely miss a seismic shift in the history of his times. Like Rorty and Fukuyama in the 1990’s, Gibbon thought that European civilization had truly arrived and that history had effectively ended for Europe in 1780.

Had Gibbon looked even at his own field of expertise he could have known his dream was doomed to fail. Yes, the reign of the mild, intelligent, and reasonable Antonines helped Rome. But the reaction against this was swift and brutal, beginning with Commodus and not really ending until 150 years later–a period that included decades of conflict between Rome’s generals. The Antonines could not quite connect with the real heart of Rome, and could not feed their souls on mild urbanity.

Lawler asserts that Tocqueville felt his dilemma keenly. Aristocracy relies on a kind of fiction and cannot stand up in argument to the exacting syllogisms of equality. Aristocratic societies, like tradition, just “exist.” Tocqueville had no arguments, but he saw the spiritual vacuum democracy could easily produce. The logic of equality satisfies our minds, but inclusion into the great mass in the middle would do little for our hearts. He feared what the absence of virtue would do to democratic societies.

Walker Percy’s novels touch on a similar theme as Tocqueville. He came from an aristocratic southern family, and he saw that their time had come and gone. Novels last The Last Gentlemen deal with the tension of knowing that the old way of living no longer works and not knowing how to replace it. In time Percy’s characters grow weary of “democratic diversions” and begin seeking something else. Percy knows that, while the southern aristocratic answer is better than nothing, it failed for the right reasons.** The quest must continue, but in what direction?^

Today we seem to be at another point of whether we will reaffirm something of what it means to be an American in a traditional sense, or change it dramatically, or, as is more likely, do some of both. We are discovering that the pragmatic, ‘rational,’ and soulless plurality of self-interest espoused by Gibbon, Rorty, and Marcus Aurelius has a definite shelf life. Commodus “went native,” the French Revolution unraveled centuries of tradition and killed thousands in the process, and today we have white nationalists and Antifa radicals. Thankfully for the moment we’re not nearly in the same place as Rome and France found themselves (or for that matter, the situation of Germany in the 1930’s after the ‘devil-may-care’ Weimar era).

Whatever merits may have been in rejecting the various “gods” of our past, we should be careful in discarding them wholesale.

When an unclean spirit comes out of a man, it passes through arid places seeking rest and does not find it. Then it says, “I will return to the house I left. On its arrival it finds the house vacant, swept clean, and put in order. Then it goes and brings with it seven other spirits more evil than itself, and they go in and dwell there; and the final plight of that man is worse than the first. So will it be with this wicked generation.” — Matthew 12:43-45

Dave

*Of course the mass of people must have someone to follow, and so we do have makers of taste and opinion. Perhaps a cynic of democracy might agree that these people alone have true freedom. But, an even greater cynic might point out that even these people quickly become subjects of mass opinion, and the people turn on them quickly when they fall out of line.

**I have read very little about the Civil Rights era, but Percy’s brief essay “Stoicism in the South” is the best analysis of why well meaning southern elites failed to bring about civil rights reform in the decades after the Civil War.

^My favorite novel of Percy’s is The Second Coming, a more profound (I think) sequel to The Last Gentlemen. In a famous passage found here, the character of Will Barrett wrestles with two unacceptable options of dealing with reality (warning: language). It is not quite the same as the aristocratic/democratic option, but hints at some of the same tension.

Enlightenment Liberty and its Children

The website Aeon recently posted a solid article from historian Josiah Ober. In the article Ober makes the point that democracy and liberal government — that is, rule of law, free speech, protection of minority rights, etc. — do not always go hand in hand. Indeed, we have seen many good marriages between the two concepts over time. But at times democracy has not produced liberal government, and historical examples exist of other forms of government ruling in a liberal way.

Ober states that liberal ideas that limited the power of government and enthroned the autonomy of the individual came from the Enlightenment, ca. 1650-1750. I have no qualms with this, and I applaud Ober pointing out the tension that sometimes exists between democracy and liberalism. But we should pause for a moment to consider the implications for the minority protections the Enlightenment sought to enthrone.

I’ll start by saying that rule of law brings a huge amount of good to a society. But a quick scan of the heritage of the Enlightenment will confuse us. For as we saw the rise of political and individual liberty enshrined in democratic regimes we also see a rise in slavery — at least in America.* Surely many reasons exist for the rise of slavery ca. 1700-1860 — too many for me to explore or fully understand. But we cannot deny the confluence of political liberalism and oppression of the natives and African Americans. Does a link exist between freedom and slavery?

We often hear arguments such as, “Of course pornography is bad for society. But the remedy for the evil (i.e., making it illegal) would be worse than the disease.” We hear these kinds of statements all the time, they roll off the tongue without thinking. But not long ago people used similar arguments to justify slavery. “Yes slavery is bad, but in order to have freedom we cannot give government the power to curtail it.” I don’t want to over-spiritualize the issue, but the fact remains that pornography enslaves the passions and the basic humanity of hundreds of thousands and perhaps millions of men and women. The abortion issue has similar rhetoric. I had a college professor argue that, “Yes, abortion is a terrible thing, but what you pro-life people don’t understand is that without abortion, women would not have the rights and opportunities they have today.” All over the Enlightenment view of individual autonomy we see this ghastly trade-off between “liberty” and death — be it physical or spiritual — again and again. We may have to entertain the notion that slavery often comes on the coattails of this kind of freedom.

In our history, at certain times at least, we definitely lacked the will to restrain ourselves. Historian Pauline Maier notes that at the Constitutional Convention George Mason wanted to include a provision to have all trade laws pass by a super majority. He foresaw that northern commercial interests, combined with its more numerous population, would alienate southern agricultural interests. In exchange, he willingly hoped to grant Congress the power to abolish slavery. He lost on this issue, according to him, because Georgia and South Carolina would not agree. In exchange for precluding even the possibility of the banning of slavery until 1808, trade laws would pass with simple majorities.

Sure enough, in 1860 such states complained of laws that favored northern manufacturing interests as one motive for secession (the issue also came up in the Nullification Crisis during Jackson’s presidency). Of course, they complained as well about Republican plans with regards to slavery.

In a recent interview the Archimandrite Tikhon said that,

Today . . . we talk not of the possible limitations of the freedom of speech, but of the real everyday criminal abuses of this freedom. Who are those that shout of the threat of ‘limitations’ most of all? Those, who have monopolized information and turned the media into real weapons, which are meant not only for manipulating the public conscience, but also aiming at ruining personality and society. . . . Of course, I’m for limiting speech that ruins freedom, as well for limitation of drugs and alcohol, for limitation of abortions – and everything which causes loss of health, degradation and ruin of nation. And the opportunity to watch vileness on TV, the right to be duped, the ability to develop a brutal cruelty and the lowest instincts in oneself – this is not freedom. Plainly, it is an absolute slavery.

In spite of any prohibitions man will have the right and possibility to choose evil anyway, nobody will take away this right, don’t worry. But the state must protect its citizens from aggressive foisting this evil upon them.

The man interviewing him got quite nervous at such a response, as would many in the United States today. Who should make the decisions, and to what degree, remains a very thorny question. One might even successfully argue that no good method of making that decision exists today, at least in America. But the fact that, at least in theory, we should certainly limit liberty in certain respects, appears obvious. To say otherwise is to bring pure selfishness and greed into the fabric of our lives Many would say that this has already happened.

Once we realize this we must re-evaluate the whole heritage of the Enlightenment view of liberty and the individual. The rule of law seems a nearly unqualified good. But I don’t think it need go hand-in-glove with a view of liberty that inevitably leads to slavery in some form. Law after all, by its very nature, asks us to give up some form of liberty for the good of others.

Aristotle’s Politics adds another perspective. He discusses the concept of proportionality in the state and teases out how imbalances even of virtues can cause harm. The concept of “the golden mean” drips throughout his writings. When even certain particular virtues assume too much of a place in the life of the state, it will cause harm. In this situation, the inevitable counter-reaction will cause harm, because it too will lack balance and proportion. One might posit that the whole “snowflake,” “safe space,” and trigger-warning phenomena present on some college campuses is just such a misshapen and destructive reaction to the abuse of freedom.

Tocqueville made the boring but true statement that, “Liberty cannot be established without morality, nor morality without faith.” Aristotle would add that such liberty must exist in proportion to other necessary virtues of the state.

Dave

*I know that of course slavery existed before the Enlightenment. But slavery had generally disappeared during the Middle Ages, and revived again only during the Renaissance, when certain Roman concepts of law, property, and a classical idea of liberty made its way back into the stream of European civilization. The Enlightenment built off this Renaissance heritage in many respects, and so it is no surprise that its heirs practiced a revival of slavery — something worse even than Roman slavery.

Lawyers, Guns, and Money

In his excellent work on the French Revolution, Citizens, Simon Schama makes many connections between the path of revolution and Romantic philosophy. They came to associate monarchy with secrecy–secret plans, secret councils, and the like. Romanticism preached openness to all things, to nature, to oneself, and so on. Real, authentic, people had nothing to hide. It made sense then, that real, authentic government had nothing to hide either.

The French paranoia over secrecy, Schama argues, drove much of the violence in the Revolution. Even simple misunderstandings could be evidence of “plots,” for no true Frenchman would have anything to hide. For example, Robespierre’s lieutenant Armand St. Just wrote some unpublished ideas for laws that would have taken his ideas of an open society to an absurd degree. He urged that,

Every man twenty-one years of age shall publicly state in the temples who are his friends. This declaration shall be renewed each year during the month Ventose. If a man deserts his friend, he is bound to explain his motives before the people in the temples; if he refuses, he shall be banished. Friends shall not put their contracts into writing, nor shall they oppose one another at law. If a man commits a crime, his friends shall be banished. Friends shall dig the grave of a deceased friend and prepare for the obsequies, and with the children of the deceased they shall scatter flowers on the grave. He who says that he does not believe in friendship, or who has no friends, shall be banned of ingratitude shall be banished.

But all this wide-eyed optimism did not prevent the Revolution from eventually being run by the Committee of Public Safety, which met in secret. It did not prevent informers roaming about looking for counter-revolutionaries.

With the best of intentions comes a tremendous and inevitable tension. We expect monarchies to have secrets. Monarchs, by definition, are not quite like normal people anyway. They decide things apart from the people. Democracies have different standards, which sometimes makes for more difficult choices and an unsolvable tension.

Tim Weiner’s Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA is in some respects a marvelous book. He writes  well and so the pages turn easily. Weiner’s pours gobs of research into his account. He has more than 100 pages of footnotes. Many of his citations come not from other books about the CIA, but from the agents themselves and especially from the CIA’s own de-classified documents. Weiner works for the NY Times in his day-job reporting on national security issues, so he knows the territory for this book quite well.

well and so the pages turn easily. Weiner’s pours gobs of research into his account. He has more than 100 pages of footnotes. Many of his citations come not from other books about the CIA, but from the agents themselves and especially from the CIA’s own de-classified documents. Weiner works for the NY Times in his day-job reporting on national security issues, so he knows the territory for this book quite well.

Unfortunately for me Weiner rarely delves into analysis and synthesis of his material. Maybe he wants a “just the facts” reporters perspective. That’s his strength, and if he added analysis the book might get unwieldy in size. Fair enough, but in the end the failure to plumb the depths of certain questions make this book incomplete in my eyes.

Weiter hammers away at the CIA, citing failure after failure, blown operation after blown operation. Their charter called for them to provide political leadership with crucial information that could inform decisions but they whiffed on almost every major crisis. Their most significant “successes,” such as organizing regime change in Iran in the 1950’s, backfired terribly a generation later. We had very little success recruiting agents within the Soviet Union and often relied on the intel of our allies. Internal reviews often pointed out the CIA’s shortcomings, but these reports almost always got buried and nothing changed.

Supposing that Weiner’s basic appraisal is true (which is up for debate), I would have liked more from Weiner on why the CIA failed as it did, but he offers only hints.

Time might have something to do with it. We are still a young country, with a very young intelligence service. The British, the Russians, and so on have all done this for much longer than us and would likely do a better job than us for that reason alone.

I wondered if the level of internal criticism from their own reviews is at least a partial function of personality. Many intelligence analysts might tend toward pessimism and obsession over detail. Maybe they would naturally be too hard on themselves. I stress the word “maybe.” I glanced through Victor  Cherkashin’s Spy Handler: Memoir of a KGB Officer for a different look and he confirmed some of what Weiner wrote, especially regarding our very poor handling of some of our agents behind the curtain. Cherkashin handled and helped recruit both Aldrich Ames and Robert Hanssen. He confirms some of what Weiner wrote about the Ames disaster (Hanssen was from the FBI). But he also mentioned some worthy adversaries and tough problems posed by the CIA for the KGB. His perspective gives the CIA more credit than Weiner.

Cherkashin’s Spy Handler: Memoir of a KGB Officer for a different look and he confirmed some of what Weiner wrote, especially regarding our very poor handling of some of our agents behind the curtain. Cherkashin handled and helped recruit both Aldrich Ames and Robert Hanssen. He confirms some of what Weiner wrote about the Ames disaster (Hanssen was from the FBI). But he also mentioned some worthy adversaries and tough problems posed by the CIA for the KGB. His perspective gives the CIA more credit than Weiner.

In one brief aside Weiner mentions that while, yes, the CIA proved almost inept at gathering intelligence, they did an excellent job of using money to buy influence, and they created some really cool gadgets that would be the envy of the international intelligence community. I am reminded of John le Carre’s quote that one sees the character of a country most particularly in its intelligence service.* The shoe definitely fits in this case. We specialize in gadgets and money.

But that doesn’t mean an intelligence failure per se, it could mean a different kind of success. For example, Weiner seems critical of the development of the U-2 spy plane. We would not have needed to develop such a plane if we had better human intelligence on the ground. Eisenhower worried that the plane might get shot down, and so on. True, but the plane gathered important information, some better, some worse, than an agent on the ground would have obtained. When Gary Powers was shot down it did cause problems, but having an agent captured would also cause problems, albeit of a different type. We made the U-2 because of our lack of human intelligence, but that doesn’t mean to me that the U-2 symbolizes failure, or is in itself a failure.

A review of Legacy of Ashes by the CIA’s historian, who makes this same point (among many other criticisms), is here.

But it’s in another aside that Weiner gets at the real root issue. Democracies, he mentions, simply aren’t very good at secrecy, and we’re not good at it mainly because it goes against all of our democratic instincts. Like the French Romantics, concealment means that we must be up to no good. And if we commit ourselves to democracy then we need an informed public. How an informed public, let alone informed public officials, and a clandestine agency should mix we have yet to figure out. Weiner offers no solutions. I can’t blame him, as I have none myself. I do wish, however, that he paid some mind to this tension present in every democracy.

Part of our desire for openness gives the press more freedom in the U.S. than anywhere else. We have no equivalent, for example, to England’s Official Secrets Act, which allows the British government to shut down almost any story they deem a threat to national security. The U.S. cannot do this thanks to the first amendment. Of course sometimes the government lies and the press exposes it. But sometimes the press gets it wrong and messes up the government. Weiner cites one such instance during Ford’s presidency. Ford had orchestrated a dual arms deal to both Egypt and Israel via CIA backchannels. He wanted to avoid seeming too pro-Israeli, but didn’t want Israel to know about the sales to Egypt. However we judge it, he had the intention of setting up the U.S. as an international broker between the two countries. But the press caught wind of the arms sale to Israel and published stories on it, but they had no information on Egypt. Ford couldn’t say, “Well we sold stuff to Egypt too–we’re trying our best!” for that would expose the operation.

Of course as a reporter Weiner benefits from this access and freedom. I wish he would have explored this tension. I’m not suggesting that it’s too bad that we have the first amendment, but it’s not an unqualified good. Among other things, it makes life harder for our intelligence services. Weiner fails to take this into account in his evaluation.

In his Revisionist History podcast renowned author Malcolm Gladwell takes a second look at stories that he feels got neglected by the flow of time. In his “Damascus Road” episode he looks at an instance involving the press and a CIA asset. A man named Carlos the Jackal was everybody’s most wanted list. No one could come close to catching him. Out of the blue a man volunteered his help to the CIA. He wanted no money, rather, he sought to try and make amends for the terrorist activities of his past, some of which had killed Americans. He gave us information that allowed for his capture.

Under the Clinton administration the Justice Department ordered an “asset scrub” as part of the overhaul of the CIA. How to draw a line between who stays and who goes? It seemed simple enough to say that anyone who had previously killed Americans needed let go as an asset.

The CIA complied for the most part, but this particular asset was simply too valuable. He remained on the books.

Eventually, however, a reporter found out about this non-compliance from a variety of sources. He wrote the story but met with a CIA agent before publishing it. The CIA representative got the reporter to remove some the crucial details, but not all. He pleaded with the reporter . . . the details he left in would expose this asset and seal his fate. The story was published, and the asset was killed shortly thereafter.

You probably guessed that the reporter in question was Tim Weiner.

Weiner argued that if anyone should be blamed for the man’s death, it was the CIA. They broke the law (a dumb law, but the law nonetheless) and his job as a reporter is to at times expose the misdeeds of government. He had credible sources within the CIA itself for the story. He might further argue that he had no reason to fundamentally trust the CIA with its claims, so often did they mislead and misdirect.

I can’t see it that way. Had Weiner not published the article, or even watered it down more, our asset would not have been exposed. He played a role in his death. When asked how those at the NY Times reacted to this turn of events, he said that for the most part it was business as usual. You move on to the next story.

That argument aside, I find it ironic that Weiner should so stringently criticize the CIA for not developing foreign assets when he himself had a direct hand in exposing one of their best.

Moving on to a different argument . . . I say that “Lawyers, Guns, and Money” is far and away Warren Zevon’s best song. The song’s unreliable narrator makes this one so enjoyable and so funny. Those familiar with the lyrics know that the protagonist always goes home with a waitress, and surprise, it doesn’t always work out. He goes “gambling in Havanna” and–shockingly–finds himself in hot water, then calls upon dear old dad (not for the first time, it seems) to bail him out. Yet, he remains “an innocent bystander,” who “somehow got stuck.”

Ok, the connection to all I’ve written here is weak. Mainly, I thought the song made a great title for this post. It’s a book about the CIA, after all. I do not suggest that Weiner resembles Zevon’s most famous character. But Weiner criticizes the CIA constantly throughout his work for losing track of ends and means, for never looking squarely in the mirror, for dissimulation and failure. However true, Weiner suffers from something similar. Legacy of Ashes paints with too narrow a brush.

Weiner’s characters almost all suffer from myopia. Weiner might suffer from it as well. There is no particular shame in this. It is a human problem, and not the sole property of spies.

Dave

*Le Carre is a perfect example of the principle I speculate about in the above paragraph. He is the former spy for the west who now is enormously critical of spying. His cold war novels expressed an ambivalence about the two major sides, while his post-cold war work exclusively criticizes the West in general, and the U.S. in particular. People naturally assume that this makes his portrayals more realistic, but I’m confident that’s not necessarily so.

“Kill Anything That Moves”

Nick Turse’s Kill Anything that Moves is not a comfortable book. I did not read the whole of it, and I  cannot imagine the depression that would set in for those who did. Turse continually hits the reader over the head with atrocity after atrocity that Americans perpetrated in Vietnam. By midway through, one feels a bit numb.

cannot imagine the depression that would set in for those who did. Turse continually hits the reader over the head with atrocity after atrocity that Americans perpetrated in Vietnam. By midway through, one feels a bit numb.

Turse’s subject matter hits hard, but only skin deep. There is not enough context, not enough logical build up, and this may be the reason why his book may not have the impact Turse hopes for. The work bears the mark of solid research and urgency but not sober reflection. Apparently Turse has recently come across some documents just made available from the army, which kept them secret for many years.

Kill Anything that Moves bears the hallmarks of someone desperate to share something that they have just discovered. It comes out all at once.

I know that in my experience as a teacher I am at my worst when newly excited about something. I remember how I rambled incoherently through the French Revolution for three weeks with students just after I read Simon Schama’s excellent Citizens (This happened! And then this! And then Danton did this! And Robespierre did that! Are you getting this down?).

Turse’s basic contention is that what happened at My Lai was not an accident, but a direct result of standard policies and orders routinely given by the military. That is, My Lai’s happened frequently, if perhaps on a slightly smaller scale. Of course untold thousands of civilians died due to the blanket B-52 bombing runs. But troops also deliberately targeted civilians on their “Search and Destroy” missions. “Kill anything that moves,” comes from typical scenarios where troops received orders to do this almost literally. Telling friend from foe on the ground posed terrible difficulties. They solved it by the simple formula, “If they run from our helicopters, they can be shot as enemies.” Civilians killed by mistake could be given a weapon and called “VC.” No one asked too many questions higher up because of their interest in body counts.

The book also details the “Destroy the village to save it,” strategy that we clumsily employed in various sectors. The strategy had some merit and history behind it, which Turse should have brought up. A typical mantra of insurgent warfare is that, “The peasants are the sea in which the fish swim.” If you dry up the sea, the fish perish. So if the peasants all came to our refugee camps, the VC would slowly suffocate. I believe that Alexander the Great used this strategy effectively against the Bactrians. Some say Vercintgetorix should have done this in Gaul against Caesar. The British used this with at least short-term benefits against the Boers. The fact, then, that U.S. tried some variation of this strategy should not shock us, and Turse should have discussed this. It is symptomatic of his narrow focus that he did not.

However a significant difference existed between the U.S. and these previous armies. Not every army can attempt every strategy. For a strategy to work it needs to have consistency with the society in which it originates. An army that fights against the values of its own culture will not march with any weight or support behind it, and will almost certainly lack real effectiveness.

Alexander and Vercintgetorix did not rule from consent. People expected them to do as they pleased. In South Africa the British interred not their allies but their civilian enemies. Also, the Victorian British army represented not a democratic consent-based society but an oligarchic “father knows best” ethos that could allow for more “dramatic” treatment of civilians.

The U.S’s strategy with Vietnamese peasants had nothing to recommend it. In theory the U.S. was a democratic, consent based society. For its army to then willy-nilly take peasants from their land had no internal rationale. Secondly, the U.S. had no history in Vietnam, and thus no build-up of goodwill from which to draw. And third, the U.S. executed the policy in such a clumsy and morally lazy way that it had to fail. The British at least knocked door-to-door like proper gentlemen and provided an escort. Though I do not praise the British in this strategy, at least they attempted some personal connection and took measures to protect Boer civilians, whereas the boorish Americans simply bombed and torched villages and then expected the locals to go to their refugee camps by default. Add to this, their refugee camps were dirty, unsanitary places. Nothing about this policy matches a society based on equality and consent, and everything about this policy suggests a people and an army that wanted nothing to do with this conflict in the first place.

Turse details many such blunders and moral darkness. His most compelling chapters detail the army’s policy about weeding out combatants from non-combatants. Being able to tell them apart in Vietnam would have required a great deal of patience and “on the ground” intelligence. Instead troops routinely received orders that ordered them to shoot at anyone who ran away from their helicopters. If they ran, they were VC. If they made a mistake, no problem. Put a gun in their hand, take their picture, and add them to the body count. Air Force pilots patrolling the Ho Chi Minh trail had orders to blow up anything moving south, be it man or machine, indiscriminately. God could sort them out in the end.

These chapters hit the reader in the gut but don’t get at the roots of why this happened. He doesn’t go for the head, only our emotional reaction.

So why did this happen? I have a theory. . .

Vietnam was a war no one wanted.

Johnson inherited the problem from Kennedy. No one “wants” a war, but Johnson seemed specifically ill-suited to foreign policy. It was not in his wheelhouse. He often commented how he wished Vietnam would go away so he could do what he really wanted to do — the Great Society.

Congress did not want to deal with the war either. With the Gulf of Tonkin resolution they signed away their responsibility and oversight to the president.

At least at the beginning of the war, we drafted troops from sections of society without much political importance, another way to pass the buck and avoid domestic conflict over the war.

Every manual on leadership prescribes leaders sharing burdens and sharing space with those they lead. In Vietnam, very few higher officers ever patrolled with their men. They led from desks. They too wanted nothing to do with the messiness the war entailed. So it is no coincidence that when they received casualty reports that in no way matched the weapons troops recovered, they looked away. They were already “looking away” by sitting at their desks.

With all this, we should be slow to place the brunt of the blame on the ground troops themselves. All of America owned this problem, and all of America contributed to these atrocities. Turse makes a valuable contribution to the literature on Vietnam, but I think it will take an historian with a more prophetic bent to make the most of his findings.

11th Grade: St. Francis and 60’s Counter-Culture

Greetings,

This week we wrapped up our unit on Vietnam, and shifted our focus to the domestic scene and the rise of the “Hippie” counter-cultural movement.

The hippies were hardly America’s first prominent counter-cultural movement, but its visibility and  impact may have been greater than others of its kind. Some point to the baby-boom population reaching the teen years as the main reason for the disruption in the 60’s, but surely this can only form part of the cause.

impact may have been greater than others of its kind. Some point to the baby-boom population reaching the teen years as the main reason for the disruption in the 60’s, but surely this can only form part of the cause.