You will notice the dated references from 2019 to the Covington kids caught on film at pro-life protest. I repost this in conjunction with the start of our American History class.

***************

I did not grow up watching a lot of TV, as my parents were (thankfully) on the stricter side of things in that regard. Yet, like most everyone else, I watched what I could when they were not around. Almost anything would do when these opportunities struck, and I distinctly remember even watching a few scattered episodes of Fantasy Island. Some of you will remember this show, in which Ricardo Montalban presided over an island resort of sorts, where people would come for vacations. But inevitably, guests would have some kind of unreal and usually traumatic experience, whereby certain unknown issues in their lives would attain resolution. The guests would leave happy, Montalban smiling benignly as they left.

Again, I watched this show even though I never particularly enjoyed it (it was on tv, and that was enough). What’s more, I could never grasp its basic premise or understand what was happening. Were the experiences of the guests real or not? They seemed unreal, but then if unreal, why did people feel so satisfied at the end? How could the island produce just what was needed for each guest (The Lost series, after an intriguing start, definitely borrowed way too much from Fantasy Island in its later seasons)? I remember no explanation, just that, “it had all worked out” somehow in a package that always seemed too neat and tidy

Again, the aggravations I had with the show didn’t prevent me from watching. In my defense, how can one look away from Ricardo Montalblan (still the best Star Trek villain to date)?

Much has been said about the dust-up over the brief video clips from the Pro-Life March involving the “clash” between Catholic high-school students and other protestors. I will say little here, except that

- I was glad to see some who made ridiculous and ill-founded statements retract their comments when new, extended video evidence came to light. I wish I saw far more laments that thousands of people rushed to extreme judgment of a 17-year-old after seeing 1 minute of video–in other words, the very exercise of commenting on Twitter “in the moment” is desperately fraught with peril. It wasn’t just that people got it wrong, but that no one should have commented in the first place.*

- I basically agree with David Brooks, who argued that 1) this scary and tribal rush to judgment happens on both sides** (this time the left was at fault) , and 2) the problem we have is also a byproduct a new technology (phones and social media) that we must understand more fully and use more wisely.

But as much as I appreciated Brooks’ wisdom, I think he misses something deeper and more fundamental. No one questions the impact of smart phones on how we interact with each other and the world. We should remember, however, that inventions do not simply randomly drop from the sky. They emerge within specific cultural contexts. While the phone was certainly not fated to arise in America, it makes perfect sense that it did. Apple marketed its products with the letter “i” in front, itunes, the ipod, the iMac, and of course, the iphone. Apple wanted one to think of these tools as a way to radically personalize our worlds, which fits within our cultural and political notions of individualism. It’s no surprise that their products made them billions of dollars. They did not create the need for radical personalization of our lives, they tapped into what already existed and helped us expand the horizons of our collective felt need.

I agree that we need to work as a society to understand the technologies we create, but that is just another way of saying we need to understand ourselves.

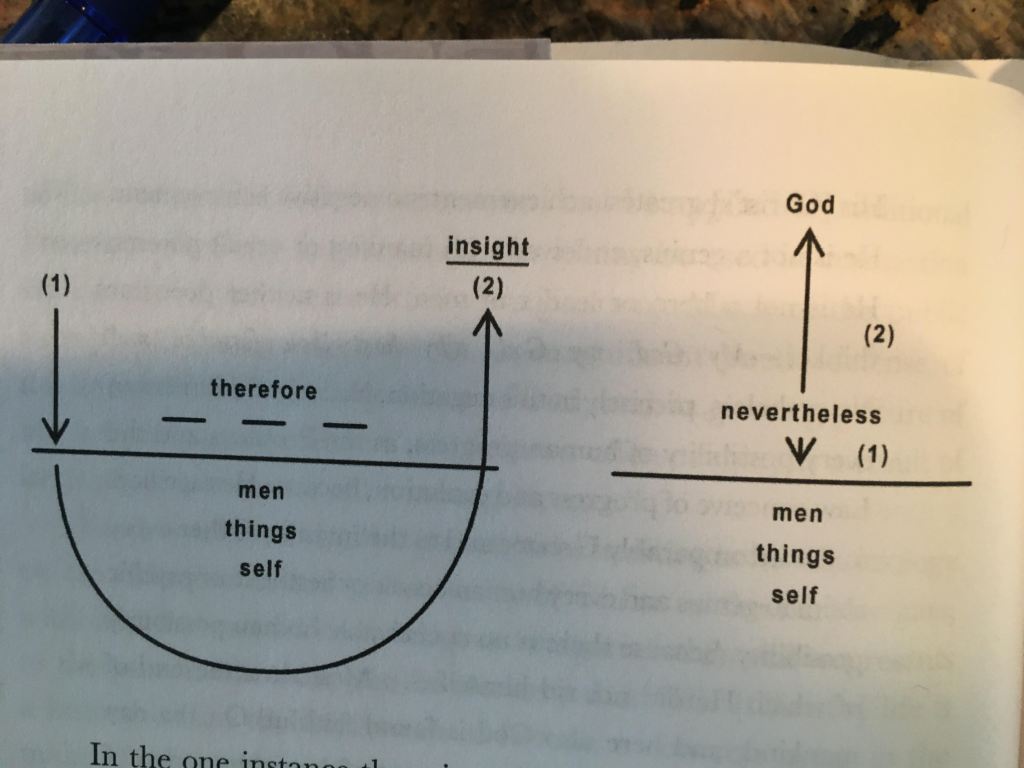

Harold Bloom’s The American Religion attempts to do just this. He argues that, as diverse as we are religiously, every culture must have some unifying belief, even if this belief remains below the level of consciousness. Bloom states that America is in fact a gnostic nation and not a Christian one, and he defines gnosticism as:

- A belief that the physical world is essentially evil, and the “spiritual” is good.

- That all people have a “divine spark” within them covered over by experience, culture, history, and materiality (the “all people” part of this is our particular democratization of what was an elitist religion in the ancient world).

- We must find a way to liberate our true selves, this “divine spark,” from its constraints. Culture, tradition, history, etc. often stand as enemies in this effort.

Bloom postulates that this faith lies underneath other professed faiths, be they agnostic, Baptist, Jewish, or Mormon. It has invaded and colonized our institutional religions and our overall mindset. He finds it particular present in Southern Baptists of his era, but today he would likely look to the various mega-churches, which operate on the idea that Sundays should be friendly, relatable, accessible, and above all, not “boring.” Ralph Waldo Emerson no doubt helped found our particular version of gnostic faith, writing in 1838 that,

Jesus Christ belonged to the true race of prophets. He saw with open eye the mystery of the soul. Drawn by its severe harmony, ravished with its beauty, he lived in it . . . . Alone in history he estimated the greatness of man. One man was true to what is in you and me. . . . He spoke of miracles, for he felt that man’s life was a miracle, and all that man doth, and he knew that this miracle shines as the character ascends.

1838 Divinity School Address

So too William James wrote that

Religion, as I ask you take it, shall mean for us the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine. . . . as I have already said, the immediate personal experiences the immediate personal experiences will amply fill our time, and we shall hardly consider theology or ecclesiasticism at all.

“The Variety of Religious Experience, 1902

We could easily sandwich Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself in between these two thinkers for the trifecta of the prophets of non-contextualized, disembodied, American hyper-individualism. This kind of individualism has as its mission liberation from other groups other entities that would seek to mold, shape, and define. And, as we look at the crumbling of institutional churches, our lack of respect for governmental instiutions, the crisis at many universities, etc. we must declare that the individualism of Emerson and Whitman has triumphed almost completely.^

I can think of few things more compatible with this faith than combining Twitter and iphones. We can both memorialize our lives (which are of course special and worthy of documentation) and express our inmost thoughts to the world at any time. Conventions of privacy, or politeness, you say? Sorry, the god of individualism is a jealous god and will brook no rivals for his throne. Do we contradict oursevles and treat others as we would rather not be treated? Well, we are large, to paraphrase Whitman, and contain multitudes. We believe firmly that our souls should have the right to break free at all times.

Thus, if Bloom is correct, if we want to avoid such miscarriages of justice in the future, we may need to do much more than get a better understanding of technology. Brooks is wrong. No quick and mysterious sitcom-like fix is in sight. We need a new religion to avoid such disasters in the future. Our nation, relatively isolated as it is, is still not an island. And, double alas, Ricardo Montalblan is not here to save us.

Dave

*I know that we need journalism, public records of public events, etc., but I will go one step farther. I don’t know why anyone was filming the students in the first place. I know this happens all the time, but it seems to me that you should go to a protest march to protest, not film others protesting. If you want to counter-protest, do so, but don’t go to film others counter-protesting. I agree with Jonathan Pageau, who argued that our incessant desire to mediate our experience through screens fits into the kind of gnosticism Bloom describes. The screen inevitably creates an abstraction, a disconnect between ourselves and reality. He writes,

It is only in the 17th century that men framed their vision with metal and glass, projecting their mind out into an artificially augmented space. Men always had artificial spaces, painting, sculpture, maps, but the telescope and microscope are self-effacing artifices, they attempt to replace the eye, to convince us that they are not artificial but are more real than the eye. It is not only the physical gesture of looking at the world through a machine that demonstrates the radical change, though this is symbolic enough, but it is the very fact that people would do that and come to the conclusion that what they saw through these machines was truer than how they experienced the world without them.

from his “Most of the Time the World is Flat,” a post for the Orthodox Arts Journal

**I am basically conservative and run mostly in conservative circles. So, while I feel that it is mostly the left that mobs people for now for breathing too loudly through their nose, I should say that the right engages in it as well. I remember some years ago glumly sitting through a presentation where a commentator dissected and destroyed the whole personality of Bill Clinton based on 6 seconds of a video clip played in slow-motion.

^Patrick Deneen has related that when he taught at Princeton, an important study came out that on the Amish that showed that more than 90% of all those who experience “rumspringa” (when as later teens they leave the community to experience the world) return back to their communities. Deneen was taken aback by how much this bothered his colleagues, who could not conceive of living a life bound by tradition and communal standards. For many of our elite Princteton dons, such a life could only be termed as oppression, and some went so far as to suggest that they should be liberated from this oppression.

This, I’m sure, backs up Bloom’s thesis all the more.