I can always count on a few “Let’s conquer Canada!” “jokes” a year from my students. We might be studying the Mexican-American War and someone will say, “No, no, no. We need to find our ‘true north’ and fight Canada!” If it’s the Spanish-American War it could be, “Spain? Why Spain? We should fight Canada!” If it’s W.W. II . . . “We fought on the same side? Phooey. After the Germans, on to Canada!”

Mild groans or exasperated rebukes (from the girls) usually ensue.

So it comes as a delightful surprise (to the boys) to actually find out that we did try and conquer Canada in 1775.

Because the idea of conquering Canada is such a passe joke, we assume that George Washington was crazy to order such an attempt. In the minds of many our invasion comes to nothing more than a madcap escapade, a schoolboy’s lark.

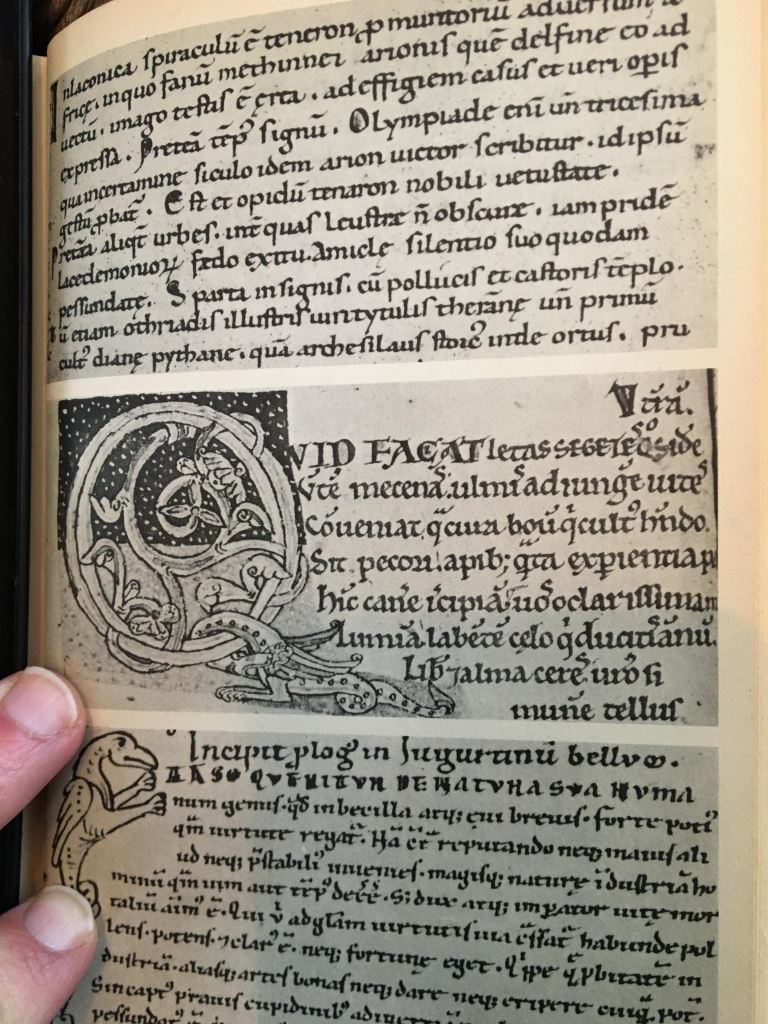

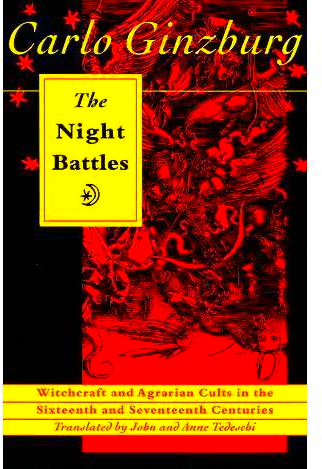

Dave R. Palmer argues in his book The Way of the Fox (newer editions have a different title  indicated by the cover to the right) that in fact such an invasion not only nearly succeeded, but also made sound strategic sense. Palmer seeks to rescue Washington from his saccharine and wooden image and recasts him as an effective and in some ways brilliant grand strategist for the American Revolution. And yes, this includes his invasion of Canada.

indicated by the cover to the right) that in fact such an invasion not only nearly succeeded, but also made sound strategic sense. Palmer seeks to rescue Washington from his saccharine and wooden image and recasts him as an effective and in some ways brilliant grand strategist for the American Revolution. And yes, this includes his invasion of Canada.

Today many think of Washington as either a great man/demi-god or nothing more than a member of elite/exploiting class. Both views are cardboard cutouts. Palmer shows us someone who thought carefully and with subtlety, someone who adjusted his thinking on multiple occasions to deal with changing reality. British generals often referred to Washington as the “old fox,” sometimes with contempt because he would not fight, sometimes with admiration for his cleverness. The moniker should stick — it brings Washington and the war to life.

First and foremost Washington stood as the perfect symbol for the Revolution. Certain qualities made him the obvious choice for command, such as his experience, his height, his bearing, and the fact that he hailed from the South. But none of these things would matter if Washington failed to think in broad strategic terms effectively. Palmer divides the Revolution into three stages, and correspondingly sees Washington adjust his strategy each time. Washington made specific mistakes as he went, but in terms of broad strategic goals Palmer has Washington never miss a beat.

Palmer argues that revolutions possess an offensive character by their very nature. They seek to effect change and so must act accordingly. Thus, Washington was entirely right to begin the war with an aggressive strategy that sought to expel the British.

This failed to fully succeed, which allowed the British to send massive reinforcements. This meant that Washington, now outmanned and outgunned, needed to withdraw and avoid having his army destroyed by a pitched battle he could not win.

France’s entry after 1778 changed the situation yet again. Now momentum and manpower lay with the Americans. Washington needed to take advantage of the alliance while it lasted. So during this period Washington should have sought to press his dramatic advantage, which he did with great effect at Yorktown.

I take no issue with either Palmer’s interpretation or Washington’s actions for phases two and three. But it’s the first phase, which includes the invasion of Canada, where we can push back most easily. It seems to me that Washington should have been cautious until the final phase where the advantage finally tipped in his favor. His aggressiveness at the start of the conflict seems out of place to me.

True, at the beginning of the war you have an emotional high that you can capitalize on. But you will have undisciplined and untested troops. What’s more, they will not yet have developed that cohesion that great armies have of sharing routines, time, space, and danger. Think of Caesar’s legions — nothing remarkable when they started into Gaul, and unbeatable five years later. In our Civil War one reason for the South’s early success had to do with the offensive burden the North faced. When General Irwin McDowell objected to offensive action at Bull Run in 1861 due to the lack of experience of his men, Lincoln replied that “[both sides] are green together.” Yes, but McDowell knew that a green attacker has a lot more to worry about than a green defender, and so it proved.

Beyond this psychological reason, Palmer asserts another more narrowly strategic goal for invading Canada. America’s size and her numerous ports put a huge strategic burden on England. Colonial armies could easily retreat inland and lead British forces on goose chases through the wilderness. Add to that, the layout of the land presented very few “choke points” at which the British could use their superior manpower to any real effect. Perhaps the only such point lay at the nexus between England and Canada — the Hudson River.

Flowing from north of Albany down to New York City, British control of the Hudson would have allowed them to control the upper third of the colonies. Controlling New York and Boston would have meant control of America’s biggest ports. Cutting off New England would further mean nabbing most of the colonies financial resources and a hefty portion of its intellectual political capital. Everyone on both sides of the Atlantic agreed that control of the Hudson could determine the war.

So if it makes sense for Washington to defend the Hudson, why not go just a bit further into Canada itself? To capture Quebec would have given the colonies everything else in Canada. Success would have prevented England from having a free “back door” entry point into the colonies via the St. Lawrence River. Shutting down the St. Lawrence would topple another domino by cutting off England from potential Indian allies* out in the west.

Reading Palmer’s lucid and logical defense, I found myself almost persuaded. Palmer urges us to remember that the failure of Benedict Arnold’s invasion (yes, that Benedict Arnold) — and it nearly succeeded, does not prove that the idea or the goal was faulty. Had it paid off, the war might have been over within a year or two instead of eight.

Yes, but . . .

Arnold lost in Quebec and Washington lost in New York City. Palmer gives a generous interpretation of Washington’s actions in New York and believes that politically speaking, Washington had to defend the city. Maybe so. But if he had to defend the city for the sake of politics, then why also invade Canada and divide your forces? Palmer wants it both ways. He believes that circumstances called for an aggressive campaign in 1775-early ’76, but that politics and not military necessity alone forced Washington’s hand to defend New York. This seems to admit the fact that Washington should have given ground and played defense in New York alone.

All in all I agree that Washington brilliantly guided the colonies to victory, and Palmer argues this decisively. He points out also that Washington faced a bungling and confused command structure in England. But Washington had Congress to deal with, who although more intelligent and capable by far than their British counterparts, had much less experience in running a war. By any measure, Washington deserves his place as one of the great generals of the modern era.

But I can’t let go of the invasion of Canada.

If we try and evaluate Washington’s gambit in Canada we should try and compare it to similar kinds of military actions across time. My case remains that the invasion made logical sense in a certain way. He was not reckless or foolhardy to try. But I feel that he should have focused more on defense, and perhaps even success might have hurt him in the long run. The colonies might have had the direct motivation to expel the British, but would they support long-term the occupation of Canada?**

I can think of three campaigns that might be comparable in certain ways . . .

- Athens’ invasion of Sicily in 415 B.C.

- Hannibal attacking Rome directly instead of defending Spain

- Napoleon going on the offensive in Belgium in 1815 instead of rallying the people to “defend France.”

- Our invasion of Iraq in 2003***

Sometimes foxes can be a bit too clever. Still, unlike Athens, Hannibal, and Napoleon, Washington committed a relatively small portion of his forces to the plan. As a general most would not rank Washington with Hannibal, Napoleon, and the like. But Palmer argues that not only should we put Washington in their company, but given his military and political success, make him the general of the modern era.

Dave

*This no mere fancy. In 1777 the British did invade via the St. Lawrence and did gather some Indian allies for their “Saratoga” campaign. That escapade ended in disaster for the British, but Washington’s strategic fears did come true nonetheless.

**Strange as it may sound now, Palmer points out that the motivation to occupy and settle Canada ourselves might have existed not on strategic but religious grounds. Many in 1775 saw Canadian Catholicism as a mortal threat to our freedoms and would have gladly occupied it in the name of liberty. Certainly we showed the ability to expand and settle territory in the west. Why not in the north as well?

***Right or wrong, Bush enjoyed overwhelming support to fight in Afghanistan in 2001. It made sense to us in the way that (again, right or wrong) responding to Pearl Harbor made sense. But his case in 2003 was much less compelling, at least to the international community.