I picked up Tillman Allert’s The Hitler Salute: On the Meaning of a Gesture primarily because I wondered why the infamous gesture could catch on so fast.

the infamous gesture could catch on so fast.

Two years after the Nazis took over a book of manners got published which listed and illustrated different forms of proper greetings. Granted, the Nazi salute of outstretched arm with the accompanying “Heil Hitler!” got pride of place. But the book also gave fourteen other accepted and traditional greetings, including handshakes, formal bows, hugs, curtsies, and kisses. But a few years later, as one young German named Helga Hartmann recalled, things had changed:

I was five years old and my grandmother sent me and my cousin . . . to the post office to buy stamps. . . . We went in and said, “Good morning.” The post-office lady scowled at us and sent us back outside with the words, “Don’t come back until you’ve learned your manners.” We exchanged glances and didn’t know what we had done wrong. My cousin thought maybe we should have knocked, so we knocked and said, “Good morning” again. At that point, the post-office lady took us back outside and showed us that the proper German greeting when entering a public building was a salute to the Fuhrer. That’s my memory of “Heil Hitler!” and it has stayed with me to this day.

I firmly believe in the power of tradition over time, and the peril societies court when they chuck it wholesale. It should never work. And yet, it some sense the Nazi’s utter abandonment of many very basic social customs “worked” for a time. With obvious exceptions (see the photo below), an entire society changed its form of greeting in an historical blink of an eye.

Allert’s book helped answer my question, but he spends most of his time discussing the sociological aspects of personal greetings, and this proved a welcome surprise for me–though I should have guessed it from the title.

Understanding both the greeting and its rapid ascent we need to see Germany in context. German culture has a long history, but not the German nation. As a distinct political entity “Germany” did not exist until 1871. For centuries the patchwork collection of provinces and principalities had been the happy hunting grounds of older states such as France, Austria, and even Russia. In the mid-18th century Prussia emerged in its own right largely thanks to its military and somewhat autocratic kings. But it took both the Industrial Revolution and Bismarck a full century after this to unite Germany under Prussian political guidance.

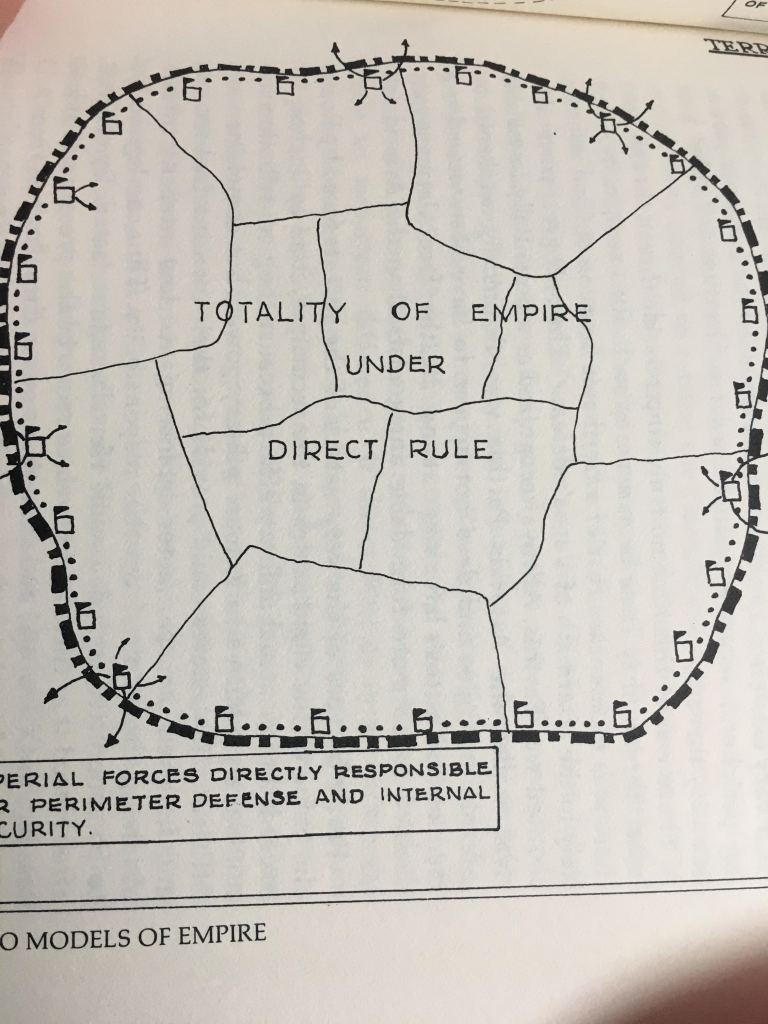

Bismarck had certain key goals in German unification. Above all he wanted to avoid uniting Germany along democratic lines. Each major leap forward in the process of unification happened because of wars–the application of force. After Prussia won the Danish War, the Austro-Prussian War, the Franco-Prussian War, Germany lost W.W. I. The Versailles Treaty only added to Germany’s humiliation and frustration at the terms of the peace, their geo-political “encirclement,” and so on. The lackluster Weimar Republic and the accompanying degradation (real or perceived) of German culture fueled the desire to reaffirm German unity. The push for a universal German greeting began in earnest.

Allert directs our attention to the nature of greetings themselves. Even a simple “hello” invites someone into a personal space, and creates the possibility of more/deeper personal relationships. Almost all social greetings have this character. We request that others allow us into their world as we invite them into our own.

“Heil Hitler!” functions much differently. It demands rather than invites, and here we see a link back to the means of German unification itself under Bismarck. Germany became Germany due to force and political manipulation. Now the “German” greeting will bring social unity in the same way–by force. Allert astutely points out that “Heil Hitler” cannot even be called a personal greeting, as it involves no personal contact (as a handshake) and no sign of individual respect (as a bow or curtsy). It immediately makes a division between the abstract mass of those who support the regime and the undefinable minority of those who do not.*

Perhaps this helps explain why the new “greeting” caught on so quickly. It is not a greeting at all. We can imagine the awkwardness of switching from saying, “Hello,” to “A merry-jolly day to you,” or something along those lines. It probably wouldn’t stick. But if we had to stand on one leg and look at the ground instead instead of saying “hello,” maybe that might have a better chance?

“Heil Hitler” shares much in common with other aspects of Nazi life. Just as this “greeting” is not really a greeting, so too the goose-step march is not really a march. Both de-personalize and therefore dehumanize life. This clues us in that the Nazi’s cared not so much for “Germany,” or their warped idea of purity, but ultimately about their perverted idea of the so-called beauty in death. Their desire to raise the stakes of a personal greeting speaks of the nihilism at the bottom of their philosophy (which Father Seraphim Rose alludes to in his brief article below).

Dave

*In their recollections many recalled that they could always tell where their teachers stood in relation to the regime by how they “greeted” the students with the obligatory “Heil Hitler!” at the start of class. None (I presume) could have taught without saying it. But some teachers always looked for ways around the full measure of obligation. One remembered that a particular teacher always walked in the door carrying large stacks of papers under his arms, making it “impossible” for him to raise his arm as he likely said “Heil Hitler.” Another entered invariably with a piece of chalk in his hand already. He would raise his arm to begin writing on the board, then turn to the class and say “Heil Hitler” with his right arm still lingering on the chalkboard. I have much sympathy with these teachers, whatever their circumstances might have been.

This, however, is a better epitaph . . .

From Seraphim Rose . . .

The chief intellectual impetus for Vitalism has been a rejection of the realist/scientific view of the world, which simplifies things and “dries them out” of any emotional life. Unfortunately, however much the Vitalist might yearn for the ‘spiritual’ or the ‘mystical,’ he will never look to Christian truth to fulfill this need, for Christianity for them is as ‘outdated’ for him as the most dedicated rationalist.

The Christian truth which the Enlightenment undermined and rationalism attacked is no mere philosophy, but the Source, the Truth of life and salvation, and once there begins among the multitude a conviction that Christianity no longer remains credible, the result will be not an urbane skepticism imagined by the Enlightenment, but a spiritual catastrophe of enormous dimensions, one whose effect will make itself felt in every area of life and thought.

Towards the end of the 19th century, a restlessness and desperation had begun to steal into the hearts of a select few of Europe’s intellectual elite. This restlessness has been the chief psychological impetus for Vitalism; it forms the raw material that demagogues and craftsmen of human hearts may play upon.

Fascist and National Socialist regimes show us what happens when such craftsmen utilize this restlessness for their own purposes. It may seem strange to some that such restlessness would manifest itself in places that had reached the seeming pinnacle of human cultural and political achievement, but such manifestations should not surprise us . . . .

Perhaps the most striking examples of this unrest manifest themselves in juvenile crime. Gangs roam about and have senseless wars with each other, and to what purpose? Such criminals come from the “best” elements of society just as from the “worst.” When questioned, such people talk of boredom, confusion, an unidentified “urge” to commit these acts. No rational motive appears for their actions.

There are other less violent forms this unrest takes. In our own time we see a passion for movement and speed, expressed especially in the cult of the automobile (we have already noted this passion in Hitler), and in our adulation of athletes. Add to this the universal appeal of television, movies, videos, which mainly serve to distract us and allow us to escape from reality both by their eclectic and “exciting” subject matter and the hypnotic effect of the media themselves; the prevalence of sexual promiscuity, being another form of the “experimental” attitude so encouraged by the arts and sciences.

In such phenomena “activity” serves as an escape–an escape from boredom, meaninglessness, and most profoundly from the emptiness that takes possession of the heart that has abandoned God and refuses to know their own selves.

In politics, the most successful forms of this impulse have Mussolini’s cult of action and violence, and Hitler’s darker cult of “blood and soil.” Vitalism, in its quest for life, smells of Death [and indeed leads to death]. The last 100 years have shown a world-weariness and its prophets have declared the end of the Christian west. Beyond Vitalism there can only be the Nihilism of destruction. Nazism itself had this function. Joseph Goebbels wrote,

The bomb-terror spares neither the rich nor poor; before the labor offices of total war the last class barriers have had to come down . . . . Together with the monuments of culture there crumble also the last obstacles to the fulfillment of our revolutionary task. Now that everything is in ruins, we are forced to rebuild Europe. In trying to destroy us, the enemy has only succeeded in smashing its own past, and with that, everything outworn and old has gone.