I have always thought, along with C.V. Wedgwood and others, that Charles I got a raw deal in the aftermath of the English Civil War (1642-49). Leaving aside the matter of his personal guilt, I can see no good legal argument for Parliament having the authority to put him to death after their victory. But as many have remarked, as sympathetic a figure as Charles cuts at his trial and the end of his life, one finds it hard to embrace him as king.

In discussing this, many pay attention to the combination of poor decisions, occasional overreaching, ideological and religious foment, and bad luck during his reign. Some perhaps mention that in addition to the above factors, Charles simply lacked the ability to “look the part” of King of England, and this I think gets more to the root of the issue.

But why would this be? Charles had a personal piety and beliefs in tune with the vast majority of his countrymen. His real leadership flaws should not have risen to level of revolution and the loss of his head. After all, he had certain strengths as a leader as well. Something else must have been going on within England, perhaps even on a subconscious level.

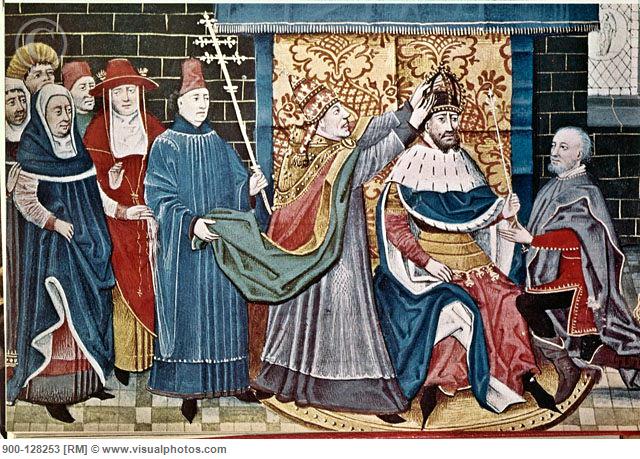

A hint lies in the coronation celebrations, or lack thereof, in the reigns of Elizabeth I and the unfortunate Charles. Several accounts exist of Elizabeth’s coronation procession into London, the first from an Italian ambassador:

The houses on the way were all decorated; there being on both sides of the street wooden barricades, on which the merchants and artisans of every trade campe in long black gowns lined with hodds of red and black cloth . . . with all the emblems and banners–it made a very fine show. Owing to the rain there was much mud, but the people had made preparations, by placing sand and gravel in front of their houses.

[He estimates perhaps 1000 horses in the procession], behind which came the queen, in an open litter, trimmed to the ground in gold brocade. She herself dressed in royal robe rich in golden color, and over her head a coif of gold. Her crown was plain, with no gold lace, but studded with precious gems.

Another commented,

Onlookers noted, “For in all her passage she did not only shew her most gracious love toward the people in general, but also privately if the baser personages had either offered her any flowers or the like as a sign of their goodwill, she most gently staid her chariot and her their requests.

Thomas Mulcaster [Ass’t to the Lord Mayor of London?] added, “London was showed a most wonderful spectacle of a noble-hearted princess toward her most loving people, and the people’s exceeding comfort in so worthy a sovereign.

Holinshed’s Chronicles notes [I have updated the spelling]

For in all her passage she did not only shew her most gracious love toward all the people in general, but also privately if the baser personages had either offered her grace any flowers or any other sign of their good will, she most gently, to the common rejoicing of all onlookers, staid her chariot and heard their requests.

David Bergeron comments that,

The whole report creates the unmistakable impression that this queen in the golden litter forms very much a part of the action, one of the actors in the pageant, part of the theatrical experience.

English Civic Pageantry, 1558-1642, p. 20

Accounts exist of Elizabeth’s own words:

I thank my Lord Mayor, his brethren, and you all. And whereas your request is that I should continue your good lady and queen, be ye ensured that I will be as good unto you as ever any queen unto her people. No will in me can lack, neither do I trust that I lack any power. And persuade yourselves, that for the safety and quietness of you all, I will not spare, if need be, to spend my blood, God thank you all.

As for Charles’ coronation, we have the following from the Earl of Pembroke, 25 of May, 1626:

My Lord,

Whereas your lordship and the rest of that Court now formerly directed by letters from the right honourable Earl Marshall, to prepare and erect in several places within the city various and sundry pageants for the fuller and more significant expression of your joys upon his Majesty, and his royal consorts intended entrance through your fair city: His Majesty having now allowed his said purpose, and given me Command to signify such to you, it may please your Lordship to take notice therof by these, as also remove the said Pageants, which besides the particular charge they accrue, do choke and hinder the passage of such as in coaches or carriages that have occasion to go up and down.

Charles’ desire to save money actually was mostly moot, as many of the preparations had already been made for his procession. Workers would still need paid. Perhaps Charles had no knowledge of this, but I think not. Rather, Charles, unlike Elizabeth, could not force himself to go through with the public spectacle of coronation. Perhaps this was his introverted and private personality. Or perhaps his sense of royal dignity was so acute as to be intensely personal, and thus misguided.

Either way . . . Elizabeth clearly understood how to embody what it meant to be queen, and she communicated that understanding in a publicly meaningful way. By meaningful, I mean liturgical. One sees this throughout her reign. She mastered the art of the “royal progress.” Theatrical and symbolic encounters, such as when a child might present her a book and a flower, or a peasant giving her a trowel, or whatever, she made look completely natural and appropriate. This I am convinced is the key difference between Charles and Elizabeth. Charles modeled himself on Elizabeth in certain respects and even in certain laws (i.e., the Ship’s Tax). But it all fell flat. Charles could not embody and transmit the meaning of his kingship effectively to enough of his people.

We see this difference in portraits of the two monarchs. Elizabeth revels in overtly outward display.

To many today she no doubt appears ridiculous. Indeed, it seems that Elizabeth Tudor hardly appears at all. But “Elizabeth I” is in full view, and the English responded to her.

Scouring Google, I think Charles seems to be holding something back in every image I saw.

And . . .

Perhaps those like me feel sympathy for Charles even if we might not like him very much because his portraits reveal something of the man that was Charles Stuart. But where is Charles I?

As for his son Charles II, say what you will, but he certainly knew how to project, both as a young man, and later in life.

The first image might let Charles Stuart Jr. bleed through a little bit, but it is at least a more likeable person than Charles I that we see. As he got older, he learned to be more fully Charles II. Alas for Charles I–during his reign much less religious persecution existed than under Elizabeth, and he certainly had far superior morals than his son, all to no avail. His morally reprobate son was far more popular and effective as king.

I think many miss a central lesson we can draw from Elizabeth and the Stuart kings: if one can’t communicate outwardly the meaning of leadership through symbol and liturgy, then people will be driven inward in the fraught and dangerous realm of ideas and ideology.

In his Myth and Reality Marcel Eliade made an observation about modern art that struck me with great force. He notes the decline of a common symbolic language and forms in the wake of the Reformation, and perhaps especially after the Enlightenment. The lack of a common outward symbolic language–the Enlightenment called such things “superstitions”–leads then to a destruction of a common visual language in the arts. Eliade writes,

Beginning with painting, this destruction of language has spread to the novel, and just recently [writing in 1963] to the theater. In some cases there is a real annihilation of the established artistic universe. Looking at some recent canvases, we get the impression that the artist wished to make a ‘tabula rasa’ of the entire history of painting. There is more than destruction, there is a reversion to chaos . . . *

I found Eliade’s book in turns deeply illuminating and frustrating. But one only needs to think of cubism, dadaism, Jackson Pollack’s work, and some of Picasso as well, to see the force of his statement. Perhaps his greatest insight came with his assertion that the rise of psychotherapy directly accompanied the destruction of forms in the art world. With outward and visible avenues of meaning eliminated, we retreated inward for answers. But Eliade points out rightly that we are still following the mythological tropes. We still seek the lost paradise, (the Romantic movement) we still seek to deal with original sin (for the SJW’s this is ‘prejudicial conduct’), and we still seek the end of history (communists and other utopians). Without the common language, however, our fights will grow only deeper. Without something transcendent outside the system for us to reference, we will have to put all of our eggs into our earthly baskets.

Both Presidents Trump and Obama understand/stood very well, consciously or no, how to embody certain symbolic types. No one much cared how much money Elizabeth spent if she fit the part so well. So too, Mitt Romney could never equal Obama’s symbolic value. If Democrats want to beat Trump, they will need someone who can equal Trump’s archetypal value to the culture, even if it is a different archetype. Presidents Clinton and Reagan also excelled at politically embodying the “meaning of America” for their eras. Whitewater/Lewinsky and Iran-Contra might have sunk other leaders with less symbolic/liturgical footing with the culture at large.

Recently a government sponsored arts festival in Germany ran for a week, with its basic message being that, “European democracy is, and always has been, racist construct based on power and prestige,” later declaring that, “wretchedness is the basis of all art.” Such sentiments have a lot in common with the conspiracy theories of those like Alex Jones. Conservatives like myself who lament such things have to take Eliade’s insight seriously. The German ‘festival’ (which sounds like something from “Sprockets”), Jones, and others testify to the loss of a common narrative, a common language made manifest in the culture we can all adhere to. I am wondering if an Elizabeth I or even a Charles II** might emerge, if not in America, then hopefully somewhere else.

Dave

**Eliade could have mentioned movies as well. Think of all of the grand epic films of the 1950’s, with their oversized sets and out-sized acting. Charlton Heston has something in common with Elizabeth I. In The Magnificent Seven, the inner life of the heroes is not important and not explored. Charles Bronson’s character–rugged individualist that he is–knows he is not the hero. Fast forward a few years to the Guns of Navarone, where David Niven’s character is played with a sense of restraint and knowing detachment (though Peck’s character rebukes him for this). The common forms still hold, but we see possible cracks in the foundation. Just about 10 years after Bronson’s turn in The Magnificent Seven, his (and Donald Sutherland’s) knowing smirks in The Dirty Dozen testify to the imminent collapse of the common forms. Of course in Europe this shift probably happened decades earlier.

Here I do not seek to romanticize the 1950’s or any other previous era. Every time and place has its problems. I just seek to point out the differences.

**For the record, I have no great love for either monarch. Elizabeth persecuted many Catholics, and Charles II would have been hard for me to respect, though I acknowledge he was popular for a reason. What we need is someone like them whom we can rally around not in terms of his policies but as a symbol. Many of the best monarchs understood this intuitively, as thinking “symbolically” was part and parcel of their culture.