I recently heard an interesting interview with author Paul Kingsnorth. Some years ago Kingsnorth was a prominent advocate for the environment.. He ceased his activism, though has kept most of his beliefs about the environmental and sociological issues western civilization faces. Kingsnorth also recently converted to Orthodox Christianity, which–while not the same as moving to Texas and becoming a Baptist–still puts him at odds with aspects of many environmental movements (for a few at least, Christianity is the cause of our environmental degradation with its teaching about man’s dominion over creation).

Again–Kingsnorth agrees that many problems exist. But he has come to believe that

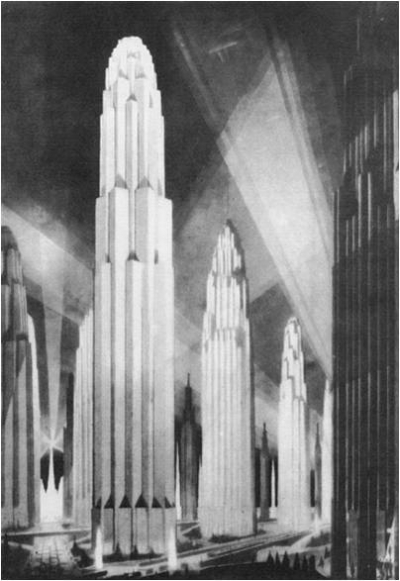

- Some of the solutions many advocate are in fact part of the problem. Technological advances will not save us–be those advances in carbon reduction, green energy, etc. To look to “Science” and “Progress” for help is to look to what got us in this mess in the first place. For example, electric cars are no doubt better for the environment than gasoline engines, but one still has to do a lot mining to get the materials for the batteries of those cars.

- Activism spends too much time telling people what to do (which naturally provokes resistance) and not enough showing them how to do it.

More importantly, he added that

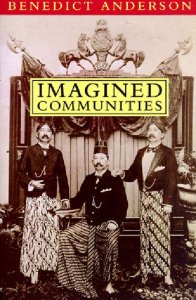

- People may want to change, but our choices actually have very little “choice” in them. The whole concept of the “market” has helped create many of our environmental problems. But–all of our “stories” we tell ourselves involve the market. We market ourselves, and our causes, on social media and elsewhere. We seek to maximize ourselves just as we seek to get the best deal on a mattress.

- So, in the end–change seems impossible within current framework.*

Kingsnorth has now dedicated himself to trying to create a different framework for himself and others through rediscovering old stories and crafting new ones, something he has done with his novels, The Wake, Beast, and Alexandria. Of course, I hope I have represented his views fairly–I encourage you to listen to him yourself.

Hearing Kingsnorth made me curious to try and explore the question of the market, and this led me to Harvey Cox’s The Market as God. I tend toward conservatism (whatever that means), so I thought it important to check out a more liberal voice on the question. A few aspects of Cox’s analysis raised my ire. He critiques aspects of the Christian tradition, which I’m fine with as far as it goes. Certain aspects of Christian tradition should come in for critique.** But heaven forbid that Cox put other religions under the same lens. For many on the left, what is “other” always stands superior to what is one’s own. But Cox showed nuance and thoughtfulness in other areas that helped me read on (such as his correct refusal to name Adam Smith as the patron of self-interest and unbridled capitalism). He picks some low-hanging fruit, but also explores deeper questions about where we find ourselves.

Most analyses of capitalism focus too much on surface questions, i.e., how much utility does the market have for society? Cox moves through this territory quickly. First, people will inevitably create markets. And, markets obviously accomplish many functions that benefit society. Cox acknowledges the persuasive power of arguments within the Christian tradition on behalf of the Market. Michael Novak, a conservative Catholic, argues that

- God made man in His image, which gives mankind the capacity to create things of value

- Societies should be constructed so that this God-given aspect of man can flourish

- Thus, whatever impedes this creative faculty in man, be it burdensome regulation, crony capitalism, and so forth, should be removed.

Novak understands the problems of unbridled capitalism combined with a competitive spirit. He also traces the effects of markets on those in poverty. Increasing opportunities for all means increasing them for the poor. Novak need not say that capitalism works perfectly to rightly argue that, while it likely will increase economic inequality, it will also raise the standard of living for all. Capitalism will not raise everyone out of poverty, but it will raise some, which is always better than none. Critics of capitalism have to acknowledge the benefits it brings.

But what I like about Cox’s book is that he is not concerned to argue about the relative pro’s and con’s of capitalism. This debate has gone on ad nauseam in many other places. He wonders not what good the Market brings (it obviously brings many benefits) but what kind of a person a Market society creates.

To start, if the Market served as a deity it would need holy days, or “feasts.” And so we have Black Friday, Prime Day, the Christmas buying season, and so on. A religion needs precepts, articles of faith. Cox mentions the idea of “trickle-down” theories, and given his background, could have leaned on this hard. But I give him credit that he went deeper to foundational ideas, not just politically divisive ones on the surface. Cox sees that every religion needs a topography, a uniform landscape where people can enter at any place. A Baptist should be able to walk into more or less any Baptist church and feel comfortable to an extent at least. The Market seeks efficiency and maximizes opportunity. For Cox, Market “faith” means much more than trickle-down theories. The Market teaches us fundamentally that we must choose, but within a set of defined parameters. Cox writes,

The Market calls not just for a monochrome outer topography. It needs an internal predictability as well. It needs people open to conversion. The Market mentality within us must match the Market that surrounds us or else the vital connection will misfire. . . . because profit derives from the mass production of countless blouses, cars, and wristwatches, a certain uniformity of taste must be generated. The problem is that human beings are not the same . . . So the Market God needs to transform people what what they once were into people prepared to receive and act on its message. . . . They have to be reconfigured to want the same thing, with manageable variations in packaging, color, and flavor.

Perhaps this explains why the Market tends to take over territory that in its inception at least, had nothing to do with Market incentives. One immediately thinks of the Super Bowl, which many now watch for the commercials. The game itself is practically secondary for many viewers. Cox briefly traces the path of Mother’s Day, Valentine’s Day, and of course, even Christmas itself, and how the Market inexorably wormed its way into how we “observe” such days. President’s Day, Memorial Day, and so on, have at least been partially transformed simply into long weekends with inevitable sales and opportunities to buy. This presence of the Market, akin to “omnipresence,” shows the deep power of Market ideology.

In light of this, liberals and progressives might face temptation to chortle on the moral high ground. But hold the phone . . . progressives gladly support the idea of corporations and organizations supporting their causes. In fact, I would argue that liberals/progressives do a much better job branding and yes, “marketing” their ideas to the culture. How else did they win the culture wars? Those on the left believe firmly that their choices define them. Their bodies are buyers in the domain of sexuality much more than conservatives. They would cry “foul” just as much as a free-market capitalist if government or culture at large restricted their freedom of choice, their freedom to “create” themselves in the market of ideas, and causes.

This is Kingsnorth’s insight. Nearly all of our discourse on the right and the left takes place within the framework of choice, opportunity and allowing us to maximize our ability to choose.

Cox holds back from saying that the Market rules all, but admits it comes close. He floats the possibility that faith in the Market god may have peaked around 2015-16. He cites data showing that Black Friday shopping has declined in recent years. This he attributes not to people shopping less, but to stores following the lead of market rationale of providing more opportunities to shoppers, thus the new trend of stores opening on Thanksgiving evening. The logic here works, of course–the Market loves more opportunities and openings–but that same logic also works against itself. Cox cites interviews with Black Friday pre-dawn shoppers. Many told reporters that they were not there for the deals so much as the spectacle, or the ritual, of Black Friday. If they got a cheap tv, great, but they came for the Black Friday experience. Without that experience, why come?

Cox wrote his book before peak Amazon and advent of Prime Day, which, following the logic of the Market, has expanded into multiple days. Nothing testifies to the Market in all its glory like Amazon. One can buy almost anything from almost anywhere, all without “wasting time” driving too and from different stories (full disclosure–I bought The Market as God used on Amazon for the amazing low price of $3.49, I think). But the problem is the same as the ones retailers face with Black Friday. The Market seeks to expand choice and possibility. Amazon, the current apotheosis of Market ideology, has followed this creed better than anyone else. But spread the butter too thin and you won’t notice it at all. Amazon has no embodied communal rituals, and religions cannot survive without them.

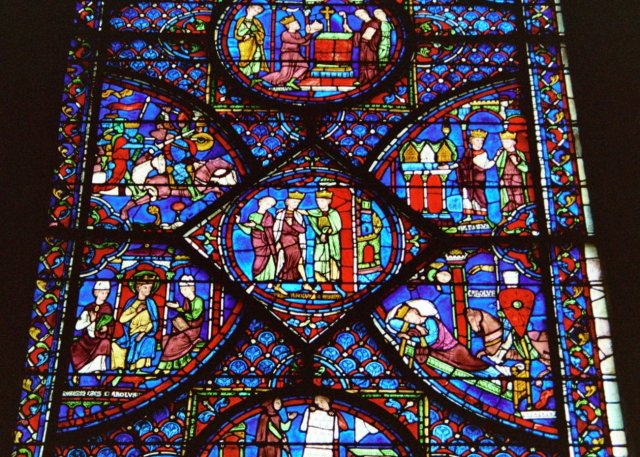

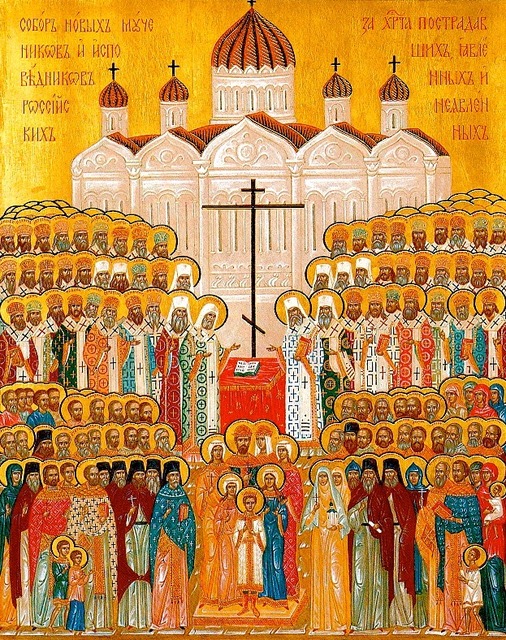

In the medieval period most markets existed within the vicinity of the great cathedrals. Some see in this a co-opting of religion, or an unholy partnership between religion and the market. Some foolish folk even go so far as to see profit as the driving force behind the building of cathedrals themselves. Cox pleasantly surprised me by seeing it differently. The point of the medievals locating markets near churches only partially had anything to do with the fact that churches existed in the center of towns. Rather, markets only really work when they know their place in a proper hierarchy, which is under the shadow of the Cross.

DM

*Kingsnorth has no issue with markets per se, but their omnipotence. I would not say that Kingsnorth is a pessimist outright, yet it seems that the main thrust of his recent writing focuses on preparing us for death, and hopefully, new life afterwards. No civilization lasts forever, and most succumb to their own internal logic reaching the end of the line. For example . . . most emissions and environmental problems come from China, and perhaps India. How can we stop this? Europe, Russia, and the U.S. went through the same process of industrialization and urban centralization in the late 19th-early 20th century. Doesn’t “fairness” indicate that they should get their turn as well? If not–would we fight a war to stop them? Aside from the monumental human cost, war would involve much more destruction to the environment than the current situation. We are stuck. If we stop, we will lose to China and others, and if we continue, we will all lose together. At least, this is one possible outcome.

**Cox has read Max Weber much more closely than I, and, unwittingly or no, he indirectly confirms some of Weber’s key ideas. It is eerily remarkable how many ‘founding fathers’ of the Market came from some kind of Calvinistic background. A connection must exist that I have yet to fully grasp.