This was originally published in 2014, then again in 2015 after Girard’s death. I post it again in light of some discussions this past week in government class.

And now, the post . . .

**************************************

I’ve said before that for the most part, I can’t stand the modern British historian, or at least, a certain kind of British historian. This is the type that Toynbee rebelled against and patiently denounced for years. This model calls for exacting discipline to attempt to focus only on the “what” and never the “why.” They see their jobs as using a microscope to discover the most amount of facts possible, but never think to lift up their heads. Leave that to the metaphysicians. Historians should tell you what happened and keep their noses clean of any other venture.

This approach has flaws from top to bottom. First of all, it’s dreadfully boring, and second, it’s a lie. We simply can’t avoid metaphysics — we will always worship and point to something, though they seek to drive ourselves and others away from such a fate.

The Abbot Suger of the Abbey St. Denis once declared, “The English are destined by moral and natural law to be subjected to the French, and not contrariwise.” Leave it to the French to say crazy things! And with historians anyway, I agree. French historians to the rescue! They have their share of great ones, from Einhard to Tocqueville, Fernand Braudel, Marc Bloch, Regine Pernoud, and so on. Historians should not forget that they too are made in the image of God, and that history has no meaning or purpose without us seeking to “sub-create” and give meaning and purpose to the world around us.*

Rene Girard fits into this mold with his great I See Satan Fall like Lightning, a brief, but dense and thought provoking book  that challenges how we read the gospels, mythology, and all of human history. A magnificent premise, and he delivers (mostly) — all in 200 pages.

that challenges how we read the gospels, mythology, and all of human history. A magnificent premise, and he delivers (mostly) — all in 200 pages.

To understand Girard’s argument, we first need to understand two main lines of thought regarding civilization. The first and overwhelmingly dominant view sees civilization as a great blessing in human affairs. Civilization allows for creativity and cooperation. It fosters a rule of law that prevents a cycle of violence from overwhelming all. Civilizations give the stability that, paradoxically, gives us space and time to challenge existing ideas and move forward.

The distinct minority believes that civilization can do no better than aspire to a lesser evil than barbarism. It at times descends below barbarism because it enacts great cruelties under the comforting cloak of “civilization.” At least the abject barbarian harbors no such illusions. The very organizing principle of civilization concentrates the worst human impulses to impose their will on others and count themselves innocent in the process. Before we dismiss this uncomfortable thought, we should note that in Genesis 4 the “arts of civilization” are attributed to Cain and his lineage, with violence as the hallmark of their work. God confuses language at the Tower of Babel because collectivized human potential is simply too dangerous. In his The City of God Augustine seems at least sympathetic to this view, as his memorable anecdote regarding Alexander the Great makes clear:

Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms? The band itself is made up of men; it is ruled by the authority of a prince, it is knit together by the pact of the confederacy; the booty is divided by the law agreed on. If, by the admittance of abandoned men, this evil increases to such a degree that it holds places, fixes abodes, takes possession of cities, and subdues peoples, it assumes the more plainly the name of a kingdom, because the reality is now manifestly conferred on it, not by the removal of covetousness, but by the addition of impunity. Indeed, that was an apt and true reply which was given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had been seized. For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, What you mean by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, while you who does it with a great fleet are styled emperor.

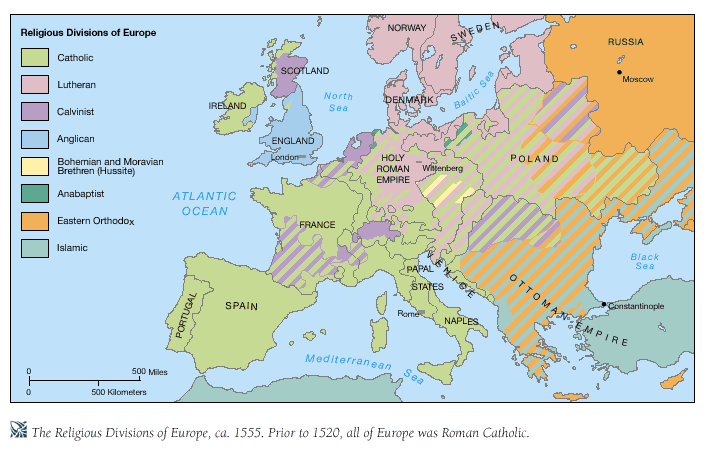

I used to associate this negative view of civilization exclusively with French post-modernists like Foucoult (not that I’ve actually read them 🙂 and therefore dismissed it. But, there it is, in Genesis 4, in St. Augustine, and likely other places I’m not aware of. So, when Girard asks us to accept this view, he does so with connection to the Biblical tradition and some aspects of historical theology (Girard accepts the necessity of government and order of some kind but never fleshes out just how he wants it to function).

With this groundwork we can proceed to his argument.

Scripture tells us that Satan is “the Prince of this world,” but in what sense is this case, and how does he maintain his power? Where he wields influence, he sows discord internally in the hearts and minds of individuals and in society in general. Hence, the more influence he has, the more dissension, and thus, two things might happen:

- He risks losing control of his kingdom, as no kingdom can withstand such division for very long.

- The chaos might incline people to seek something beyond this world for comfort, which might mean that people meet God.

How to maintain control in such a situation? Girard believes that mythology and Scripture both point to the same answer: Satan rules via a ritual murder rooted in what he calls “mimetic desire.” The war of “all against all” fostered by Satanic selfishness must be stopped or he risks losing all. Mimetic desire heightens and gets transformed into the war of “all against one.” The people’s twin desires for violence and harmony merge in an unjust sacrifice. This restores order because we have find the enemy collectively, and find that the enemy is not us — it’s he, or she, or possibly they — but never “us.” Satan’s triumph consists of

- His control restored

- His control rooted in violence

- A moral blindness on our parts

- A reaffirmation of our faith in the ruling authorities to bring about order

“Mimetic desire” has a simple meaning: we seek to imitate the desires of others, and by doing so take them into ourselves, into the community. Girard speaks at some length about the 10th commandment which prohibits coveting. While this prohibition is not unique to the Old Testament, it places greater emphasis on the problem of desire than other cultures. Desire in itself is good, but Satan, the “ape of God” gives us his desires, desires for power, for more. Once these desires spread they turn into a contagion, or a plague that infects people everywhere (Girard believes that many ancient stories that talk of a “plague” may not refer to something strictly biological). Once begun, resistance is nearly futile.

To understand this we might think of two armies opposing one another. Neither wants to fight, but both fear that the other might want to fight, so both show up armed. Once the first shot is fired, be it accidental or otherwise, all “must” participate. All will fire their weapons, and you would not necessarily blame a soldier for doing so. It just “happened,” and with no one to blame, there can be no justice — another victory for Satan.

He references Peter’s denial of Jesus just before his trial. Often our interpretations focus on the psychological aspects of Peter’s personality — his impulsiveness, and so on. Girard won’t let us off the hook so easily. Such psychological interpretations distance ourselves too comfortably. In reality, Peter fell prey to the desires of the crowd in ways that ensnare most everyone. Peter is everyman, in this case, and perhaps its more telling that he extracts himself from that situation.

Pilate too succumbs, in a way typical of politicians everywhere. Pilate needs order — his cannot afford that Justice be his primary concern. To maintain order he has no other choice but to give in. Girard would argue, I think, that this is nothing less than the bargain all rulers must make from time to time. Politics, then, get revealed as more than a “dirty business,” but one with indelible roots in the City of Man.

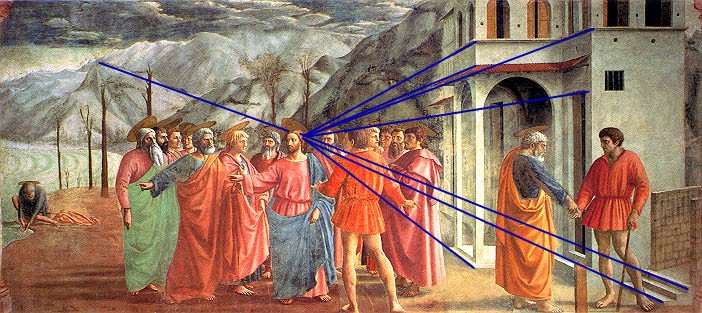

Many ancient stories show forth the nature of mimetic violence, but the Cross itself stands as the example par excellence. The people in general have no hostility to Jesus, but once they become aware that the religious authorities are divided, and the Romans start to weigh in, the plague of mimetic desire settles in. They turn on Jesus, and believe that His death will solve their problems. It looks like a repeat of other events and another victory for Satan. But this victim not only possessed legal innocence, He actually had true and complete innocence. Now Satan’s methodology gets fully exposed, for “truly this was the Son of God.” His resurrection and ascension vindicate Jesus and establishes His lordship and His reign over a kingdom of innocent victims.** This “exposure” has its hints in the Old Testament at least in the Book of Job. His troubles must be deserved in some way, so say Job’s friends. If he follows his wife’s advice to “curse God and die,” he will bring peace to the community by vindicating their perception of the world. He resists, and God vindicates him in the end.

Girard argues that Jesus does not give commands so much as introduce a new principle, that of imitation. He counters our mimetic desires not by squashing them, but by redirection. Jesus asks that we imitate Him, as He imitates the Father. The epistles carry this forward. Paul tells us to imitate him, as he imitates Christ, who imitates the Father. Well, Jesus did give commands, but his commands about love in John, at least, invoke this pattern of imitation. “A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another, even as I have loved you, that you also love one another” (John 13:34). What makes this commandment new is not the injunction to love each other, but perhaps the principle on which it is based.

So far I buy Girard entirely. His link of mimetic desire with the crucifixion, and his analysis of the nature and extent of Satan’s influence I find profound. He started to lose me a bit when talking about how so many myths follow this pattern of mass confusion, scapegoat, death, and then, deification of the victim — or barring deification of the person killed, then of the process itself. I.e., because it restored order, it must be from God/the gods. I could think of a few myths, but I’m not sure how many follow this pattern (though I have a weak knowledge of mythology and could easily simply be ignorant).

When speaking of the founding of certain civilizations, however, he seems once again right on target. In Egypt and Babylon the violence occurs between the gods. Girard suggests that some stories may have actually occurred, and then the victims like Osiris and Tiamat became gods. But in Rome at least, the violence takes place between the twins Romulus and Remus, an instructive case study for Girard’s thesis. The twins set out to found a kingdom but cannot agree on which spot the gods blessed. But the brothers cannot co-exist peacefully. Their rivalry heightens until Romulus kills Remus and assumes kingship of Rome. Livy, at least, passes no judgment on any party. This is the way it “had to be.” No state could have two heads at the helm–one had to be sacrificed for order to commence. The Aeneid also has a similar perspective on the founding of Aeneas’ line. Violence just “happened.” Such was the founding of Rome, and in later stories Romulus is deified as a personification of the Roman people. Not that everything about Rome would be evil, but the foundational principle of “sacred violence” to establish civic order has no business with the gospel.

This story is instructive for Girard, but not entirely. The deification of the aggressor fits squarely within Girard’s framework. But what of those that deify or exalt the victim? Many myths fall into this category, Persephone, Psyche, Hercules, and so on. These myths seem to prepare the way for Christ, who fulfills the stories in the flesh made real before our eyes. Girard sees mythology in general rooted entirely in “City of Man,” but I cannot share this view.

At the end of it all, however, we have a great and thought-provoking book. We should have more like them even if it means more French influence in our lives. Below is a brief interview excerpt with him.

Dave

POPE BENDICT IS RIGHT: CHRISTIANITY IS SUPERIOR

Rene Girard, a prominent Roman Catholic conservative and author of the seminal book “Violence and the Sacred,” is an emeritus professor of anthropology at Stanford University. His more recent books include “Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World” and “I See Satan Fall Like Lightning.” This interview was conducted by Global Viewpoint editor Nathan Gardels earlier this year. It is particularly relevant in shining some light on the controversial comments by Pope Benedict on violence and Islam in Germany last week.

By Rene Girard

Global Viewpoint: When Pope Benedict (then Cardinal Ratzinger) said a few years ago that Christianity was a superior religion, he caused controversy. In 1990, in the encyclical “Redemptoris Missio,” Pope John Paul II said the same thing.

It should not be surprising that believers would affirm their faith as the true one. Perhaps it is a mark of the very relativist dominance Pope Benedict condemns that this is somehow controversial?

Girard: Why would you be a Christian if you didn’t believe in Christ? Paradoxically, we have become so ethnocentric in our relativism that we feel it is only OK for others — not us — to think their religion is superior! We are the only ones with no centrism.

GV: Is Christianity superior to other religions?

Girard: Yes. All of my work has been an effort to show that Christianity is superior and not just another mythology. In mythology, a furious mob mobilizes against scapegoats held responsible for some huge crisis. The sacrifice of the guilty victim through collective violence ends the crisis and founds a new order ordained by the divine. Violence and scapegoating are always present in the mythological definition of the divine itself.

It is true that the structure of the Gospels is similar to that of mythology, in which a crisis is resolved through a single victim who unites everybody against him, thus reconciling the community. As the Greeks thought, the shock of death of the victim brings about a catharsis that reconciles. It extinguishes the appetite for violence. For the Greeks, the tragic death of the hero enabled ordinary people to go back to their peaceful lives.

However, in this case, the victim is innocent and the victimizers are guilty. Collective violence against the scapegoat as a sacred, founding act is revealed as a lie. Christ redeems the victimizers through enduring his suffering, imploring God to “forgive them for they know not what they do.” He refuses to plead to God to avenge his victimhood with reciprocal violence. Rather, he turns the other cheek.

The victory of the Cross is a victory of love against the scapegoating cycle of violence. It punctures the idea that hatred is a sacred duty.

The Gospels do everything that the (Old Testament) Bible had done before, rehabilitating a victimized prophet, a wrongly accused victim. But they also universalize this rehabilitation. They show that, since the foundation of the world, the victims of all Passion-like murders have been victims of the same mob contagion as Jesus. The Gospels make this revelation complete because they give to the biblical denunciation of idolatry a concrete demonstration of how false gods and their violent cultural systems are generated.

This is the truth missing from mythology, the truth that subverts the violent system of this world. This revelation of collective violence as a lie is the earmark of Christianity. This is what is unique about Christianity. And this uniqueness is true.

*Ok, I overstated the case. The British have many great historians, Henry of Huntington, Toynbee, and recently Niall Ferguson (British Isles), and countless others who all attempt to have the humility stick out their neck, say something intelligible, and make people think.

**In an intriguing aside, Girard points out that Christianity helped establish concern for victims for the first time in history, a great victory for Justice and the human heart. But Satan has learned to pervert this as well. Now our “victimization” culture has left off concern for justice, and instead has become a quest for power over others. I.e., “because ‘x’ happened to me, now you must do ‘y.'” We see this happen in the ancient world also, perhaps most notably with Julius Caesar’s murder and its relationship to the founding of the Roman Empire with Octavian/Augustus. Girard writes,

The Antichrist boasts of bringing to human beings the peace and tolerance Christianity promised but failed to deliver. Actually, what the radicalization of contemporary victomology produces is a return to all sorts of pagan practices: abortion, euthanasia, sexual undifferentiation, Roman circus games without the victims, etc.