Greetings,

This week we continued with the Cold War in earnest and took a look at a few key issues and events:

England and America could see the Cold War coming as W.W. II ended. The unfortunate Eastern European nations of Poland, Hungary, Rumania, and Bulgaria exchanged one conqueror for another. Soviet dictatorship may not have been as bad as Nazi occupation, but that is hardly saying much.

Atomic weapons quickly became prominent, although not necessarily because we wanted it that way. Free societies maintain themselves traditionally through a volunteer military, except in emergencies. With the war over hundreds of thousands of soldiers looked forward to returning home and resuming normal civilian life.

But the Soviets did not disband their army. They kept it active and occupied much of Eastern Europe. How could we respond? We could either:

- Keep the draft going and maintain our military at W.W. II levels, which might also mean continuing the war-time command economy.

Or

- Use atomic weapons as a kind of equalizer against the sheer volume of Soviet troops.

The latter option appealed to us for many reasons, but of course created other problems. If the Soviets eventually got “the bomb,” how then do we maintain our advantage? Do we make more atomic weapons? Or do we make them more powerful? The arms race was on, and one consequence of this was the proliferation of weapons able not to just win wars but wipe out civilization as we know it.

Another problem with nuclear weapons revolves around what exact purpose they serve. Are they weapons? This seems obvious on its face. Of course they are weapons. But can something be a weapon if you would never actually use it? No — then it’s just a very expensive and very dangerous showpiece. But could nuclear weapons actually be used? For once used, Pandora’s box opens. Could a nuclear war have a winner?

So, did nuclear weapons in reality function much like status symbols, reflecting the image of power rather than actually having power? But then again, if everyone thinks they are just status symbols, they pose no threat. And clearly, these weapons posed a huge threat. We could not contemplate the consequences of using them, and we felt that we needed to have them ready to use at a moment’s notice. These were some of the terrible dilemmas the Cold War gave us. The confusion between image and reality bore itself out in this Civil Defense video many elementary school children saw in the early 1950’s:

The idea that we may not have known exactly what we had on our hands gets reinforced from the Castle Bravo disaster in 1954.

At its core, the Cold War presented us with the dilemma of how to win a war without actually fighting the other side. How could you win a boxing match if neither opponent could touch each other? Much of our strategy revolved around the following premesis:

- Communism can only survive as a parasite. It cannot internally sustain itself, so the only way it can live is by feeding off of others. Thus, it is imperative to deny them access to new territory, for each new piece of territory will artificially extend their life-span.

- Since fighting the Soviet Union directly would have exceedingly dire consequences, we have took for non-traditional, or “asymmetrical” ways to fight. Economic advantage, and our political image, among other things, would play key roles in this conflict.

The Korean War often gets ignored, sandwiched between World War II and Vietnam. I myself usually breeze over it, but every so often the conflict makes itself very relevant. The issues involved deal with many of problems discussed above. Commentators could argue that we

- Won the war, because after the invasion of the North we pushed the North out of South Korea.

- Lost the war, because we failed to destroy North Korean forces, largely due to the intervention of China, and got pushed back out of North Korea

- Tied, because the status quo was restored, but nothing more.

While we could not go through the entirety of the history of the war, the impact of our involvement would have large, though subtle ripple effects in our own society.

- The Korean War was unquestionably a war, yet the Senate never declared war. Obviously this was not the first time that we had used troops and not declared war formally, but the scale of the conflict and commitment exceeded previous undeclared wars.

- After the Korean War we began to maintain a continuously large standing army, a break from the past.

- The war also raised questions about executive power and the role of Congress. As foreign policy came to dominate, the power of presidency inevitably increased, but for the most part, these questions have no resolution as of now.

A brief aside, every political commentator of which I am aware from the classical era down to the early modern age (Aristotle, our own founders, etc.) argued that a large standing army posed a dire threat to liberty. That is, no militarized state could maintain political freedom indefinitely. Whether they were wrong, or our exception proves the rule, or perhaps our political system has indeed suffered because of this is a point of great debate.

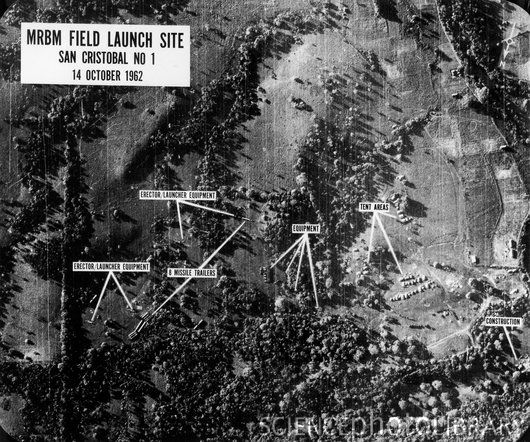

Many of these questions came to a head in October 1962 in the Cuban Missile Crisis, where under a cloak of deceit, the Soviets started building missile silos to house nuclear warheads capable of reaching at least 1/3 of the U.S. mainland. We could either . . .

- Ignore the problem. Perhaps it would not be worth it to get them out, or perhaps we did not have the political will to stop them from installing them. As parents we sometimes ignore things that we would rather not deal with at the moment. We then file the incident away to be used later if we need to.

- Acknowledge the presence of the silos/missiles, but do nothing about it, which would make us look terribly weak.

- Insist that the missiles not be installed and prepare to take action to prevent it. Easy to say, but hard to do, because it begs the question of how far we would go. Would it be worth W.W. III to prevent it? Would it be worth a global nuclear holocaust? Maybe we would not actually launch nukes, but do we then bluff and claim we would? Would that escalate or diffuse the crisis?

Records indicate that initially most favored an air strike against the silos. Most agreed that we had a good chance of eliminating the silos via bombing, with minimal casualties. But it would involve a military attack on one of Russia’s allies, and we could not be sure how they would respond. Would they then take West Berlin? What would we do then?

Perhaps these questions led Kennedy to decide on a naval quarantine which would prevent the installation of the missiles, and also give the two sides time to talk. It forced the Soviets to back down or be the first to take aggressive action.

But none of this attempts to see the crisis from the Soviet perspective. If the U.S. had concerns about missiles 90 miles from our shores, what about the fact that we had missiles 90 miles from the Soviet Union in Turkey? What about the Bay of Pigs? One could easily argue that the missiles in Cuba served peace, if you believed that strategic parity gave the best guarantee of avoiding conflict.

In the end the Soviets agreed to remove the missiles if we pledged never to invade Cuba and removed ours from Turkey, which we agreed to do, albeit secretly. Many felt that we had won, and many praise Kennedy for his handling of the crisis.

But as time passed, we learned more about just how close we came to disaster. In the documentary The Fog of War, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara discussed his meetings with Castro in 1992 below.

If these revelations are true, the air-strike we nearly decided upon would have led to disaster. When one understands the possibilities inherent when human fallibility combines with enormous destructive power, we can only thank God that nuclear war did not happen in 1962.

Next week we move on to Vietnam.

Blessings,

Dave