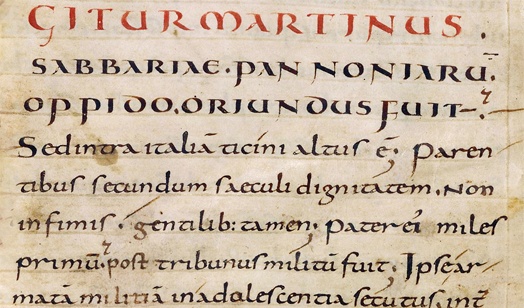

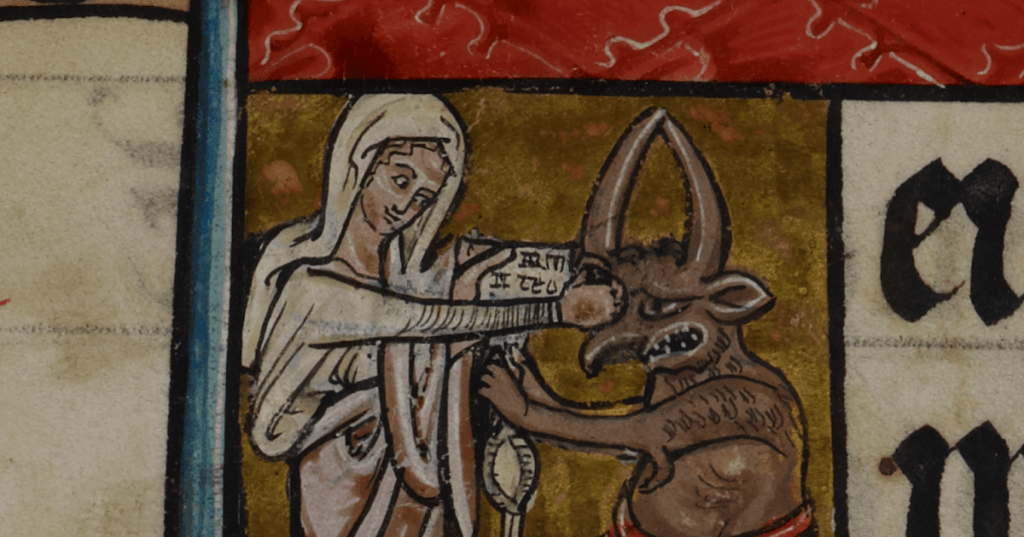

Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger’s Malleus Maleficarum (translation–possibly, “The Hammer for Devils/Witches/, i.e., “Malefactors”) ranks way up there among the more strange historical documents I have read. Published in 1484, this tome tells one all about witches and other sundry works of the devil. It deals with the reality of the supernatural quite openly and frankly, and in this way strikes us as “pre-modern.” And yet, the “hammer” the title alludes to appears to strike hardest through the use of the farthest reaches of the logic parsing of the scholastic method. Those familiar with the Summa Theologica (dating more than two centuries prior to the Malleus) can testify to Thomas Aquinas’ clarity and brevity, even if he relies possibly too much on Aristotelian logic. Aquinas leaves a certain amount of space and room to breathe in his work. It is that mystical fringe that exists in Aquinas’ best writing that gives it its staying power.

Not so Kramer and Sprenger. Though grudgingly–I have to admire their ability to go on for pages on end, giving all counterarguments incredible deference and losing the reader in a labyrinth, before finally turning the battleship slowly round towards their correct conclusion. I firmly believe that Christians should take the supernatural seriously–much more so than many do today. However, one must wonder of the efficacy of extended discussion on “Whether Witches may work some Prestidigitatory Illusion so that the Male Organ appears to be Entirely Removed from the Body”–which is only Question IX of Part One, of the First Part, or what final precautions should be observed in the trial of a witch in the eleventh action of the second examination (3rd Part, 2nd Head, q. 16).

At least one does get the sense that Kramer and Sprenger enjoy their work. Here is a very mild excerpt . . .

If it be accordance with the Catholic faith to maintain that in order to bring about some effect of magic, the devil must intimately cooperate with some witch, or whether, one without the other, that is to say, the devil without the witch, or conversely, could produce the same effect.

And the first argument is this, that the Devil can bring about an effect of magic without the help of any witch. So St. Augustine holds . . . and we learn from Holy Scripture of the disasters which fell upon Job, . . . which the Devil himself was able to bring about, with God’s permission. What a superior power has within itself to do, it may do without reference to a lesser power.

So too, an inferior power may work within its “sphere” to produce effects without reference to a power greater than itself. For Blessed Albertus Magnus says in his treatise De Pasionibus Aeris that rotten sage, if used according to certain specifications and thrown into running water, will arouse fearful tempests and storms.

Moreover it may be said that the devil makes use of the witch not because he has any need of her agency, but because he seeks the damnation of the witch. We may refer to what Aristotle says in the 3rd book of his Ethics, where Evil is a voluntary act . . .

But an opposite opinion holds, that the Devil, being unlike man, cannot readily do harm to man without the effect of material agency, such as the instrumentality of witches. For every act, some kind of contact must be established. And many hold this to be proven by the text of St. Paul to the Galatians, where the gloss on the text who have singular, and fiery eyes, who by a mere look can harm others. And Avicenna [Abn Ibn Sina] also bears this out, in Naturalism book 3, “Very often the soul may have an impact on the body of another, for such is the influence of the eyes.” And the same opinion by Ali Ghaza in the fifth book of his Physics . . . St. Thomas too speaks of this in the Summa, part I, q. 117, whereupon he states that the influence of the soul may be concentrated in the eyes.

Without any mental powers insensible bodies may produce effects, and so a living man, if he pass near the corpse of a murdered man, is often seized with fear though unaware of the dead body. Moreover, it would seem that most extraordinary and miraculous events come to passby thte workings of the power of nature, and St. Gregory points out in his Second Dialogue. The saints perform miracles, sometimes by prayer, sometimes by their power alone. St. Peter prayed and Tabitha was restored to life. By rebuking Ananias and Saphira who told a lie, he slew them without any prayer. Therefore a man by his mental influence can change the condition of another material body.*

Can any doubt that a man with courage will warm his body, and a man with fear will cool and enfeeble his body?

St. Isidore in Etymologies calls witches guilty of greater sin, for they stir up and confound the elements with the aid of the Devil, and bring about terrible storms and tempests. And Vincent of Beauvais, quoting many learned authorities in his Speculum Historiale, says that he who first practiced magical arts was Zoroaster, in the line of Ham, son of Noah, and according to St. Augustine in the City of God, Ham laughed aloud when he was born, showing that he would give service to the Devil.

When comparing Aquinas and these authors, I reminded of analogy used I believe by both Toynbee and C.S. Lewis–that bacon and eggs smells so much better when hungry at 9 am, as opposed to when satiated later in the day. Even in the text above, though I largely agree with the conclusion, the method conjures up the smell of bacon and eggs after one has eaten. The scholastic method has run its course.

That late-medievals thought seriously about witches should surprise no one. But to many moderns, the breadth of discussion, the familiarity with many texts both within and without the Christian tradition, will surprise many. When we disagree fundamentally with others, we assume that they do not have actual reasons for their belief. We assume their ignorance, selfishness, or some other such flaw. About 150 years later, an Ambrosian monk named Francesco Guazzo published a companion volume, the Compendium Maleficarum. In Book I, Chapter III he writes,

Any man who maintained that all effects of magic were true, or who believed that they were all illusions, would be a radish rather than a man.

This spirit of balance characterizes the work, which a modern must acknowledge even if one believed that witches and demons did not exist.

Of course the Devil works in various ways, both through physical and spiritual/mental means. I have no thoughts on the exact nature of the Devil’s work regarding COVID-19. What we can say in general is that the Devil always seeks to sow confusion, doubt, and fear. He is the accuser, the divider of the brethren. Just as he seeks to divide us from God, so too he brings death–a literal decomposition of soul from body, and of the various connections in our physical form. He seeks to “decompose” meaning as well, and we have certainly seen this in our society the last few months.

The uncertain nature of the disease relates strongly to this decomposition of meaning. But I feel sure that others factors must be at play, and I wonder at the manifestation of this confusion as it relates to masks. Some people, given their circumstances, probably should wear masks, but I am curious about the vast majority of us who have options and feel the tension between wearing/not wearing them. What motivates our choices, and why do those choices often divide along political lines? Liberals want more mask wearing, conservatives seem to wear them less–although the terms “liberal” and “conservative” lack a defined meeting. We should approach the subject with the method of the Malleus in mind, aware that not everyone who believes in wearing masks is a coward or out to control everyone, and those who eschew masks may not always be selfish jerks, or ignorant of “Science.”

I am sure that something else is going on, but not sure exactly what. Consider what follows speculative, and certainly incomplete . . .

Perhaps the most obvious connection might relate to debates over the last few years around free speech. Progressives want to limit certain kinds of speech in certain places to protect the “vulnerable” minority. Conservatives push against this. So progressives stress protection from the disease, even if this protection should extend far beyond those directly at risk. Conservatives who favor a more rough and tumble approach to speech might then favor the same approach to the disease. We should be tough, have thick skins, and so on.

Perhaps this might go some way to explaining the difference with mask attitudes now. But just 50 years ago, liberals championed free speech, not conservatives. And–liberals tend to prefer longer shut-downs of the economy, even though the shut-down obviously hurts the poor far more than the rich. Restrictions on the economy–favored more by progressives–also will hurt illegal immigrants–another progressive issue.** It makes sense that conservatives want order, sanctity, protection, and liberals would want freedom, and the knocking down of boundaries. But part of the confusion the world experiences lies in the lack of coherent meaning in our political designations.

With rates of abuse, depression, suicide, time on screens, opioid and alcohol use, etc. all going way up during the quarantine, we must realize that the temptation to go a bit nuts will significantly increase. And when our visible structures of decision-making and common institutions fail us–as they largely have during our various recent crises, we will revert to archetypal symbolic modes of being. When the visible symbols of unity fails us, we will retreat inward even subconsciously to find meaning and direction.

These subconscious symbolic actions make themselves perhaps most evident with masks. I have no solid thoughts here as to why they have caused such disagreement among good people. I think we have to go beyond politics (i.e., does the government have the right to order this or not?). And–let us borrow from the Malleus and assume that the Devil would like nothing better than to tear us apart. And to borrow again from Sprenger and Kraemer–no doubt both sides have good arguments that could fill many pages. I shudder to think how many the two of them could find to apply to the mask argument.^

When we think of masks, we should think of the use of veils, for masks function much like a veil. Veils have very little role in our society today. Even in weddings, very few brides today would consider wearing a veil. But most ancient societies used veils (or something like them) in many religious settings, and certainly for weddings. In the ancient world veils would be used to cordon off portions of a temple, for example. You would use veils as means of

- Protecting the people from the power/holiness of what lay behind the veil, or

- Protecting what was special/holy from intrusion by the people.

We live in a society that builds on a foundation of “openness”–trade with others, traveling from place to place with few barriers, free speech, etc. and so the notion of veils initially strikes us as odd. This “open” view of life is certainly part of existence. We cannot sustain our own lives. Whenever we eat anything, we take the life of something else into our bodies and incorporate into our own lives–this holds true for plants just as it does for pigs and cows. We do not generate life for ourselves. We must be filled from outside ourselves and ultimately, “In Him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

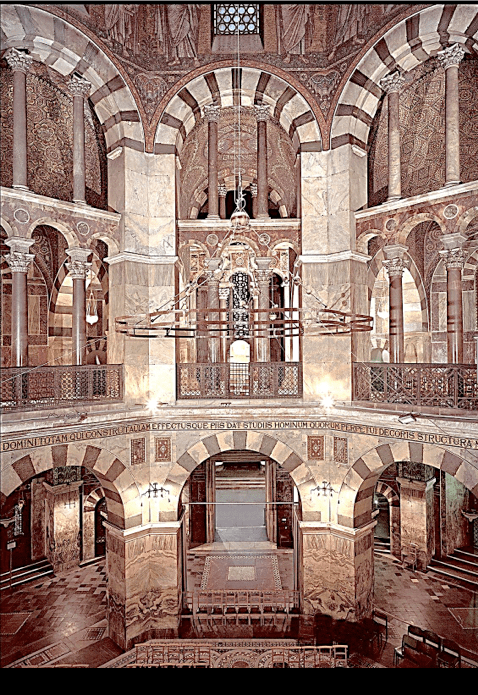

But . . . we must be “closed” to some things in order to survive. We cannot play in traffic, swim with sharks, or take candy from strangers. And other things are so powerful that we can only have a little bit of at a time lest it destroy us, like whiskey, for example. In ancient Israel the high priest went into the Holy of Holies only once a year, alone, with a rope tied around his leg to remove him in case he died from the experience.

As to veils for brides, both of the above purposes could fit. On the one hand, the bride is the most precious “item” of the day, and she is meant for her husband only. Thus she should not be “revealed” until the ceremony is completed. So too, to veil the bride is to honor her beauty and to protect us from it. This may not make sense historically or scientifically, but certainly it does mythologically–recall “the face that launched 1000 ships,” or Lucy’s desire in The Dawn Treader to say a spell that would make her “beautiful beyond the lot of mortals,” and have men and nations fight over her. In the medieval Marian office of “None” (the ninth hour) the antiphon before the psalms hearkens to the power of the beauty of the feminine:

Thou art fair and comely, O daughter of Jerusalem, terrible as an army set in array.

Song of Solomon 6:4

To wear masks in public places may be entirely appropriate and necessary, but we should understand what it means. It means, in certain respects, that we cannot act as a community of trust that mutually shares life together. And this is not necessarily our fault, as the insidious nature of the virus means that one can have it and spread it without any knowledge. But neither is it a trifling thing. To “veil” ourselves means that we set ourselves apart from society. One cannot have a conversation with a mask on–one cannot really share life with another with a mask on. It is terribly ironic that we have to “come together” in such polarized times to essentially isolate ourselves socially from each other. As Jean-Claude Larchet writes,

Through our body we reach out and communicate with others–by exchanging glances, smiles, handshakes, and so on. It is through our body that others gain their first impressions of us–our character, or our mood at the time. Our body both reveals and hides us from others . . .

I believe this accounts for much of the confusion about masks. Larchet rightly suggests that even small physical gestures of communication that we normally make at the grocery store become impossible with masks. Circumstances ask us to hold an impossible tension in our minds and we can’t quite do it. Telling the difference won’t always be easy.

In such times we may want to reach out and look for solutions and healing in what is distant from us–in our political leadership. These days we will not find it there, and likely were never meant to. We should return to our immediate center–our churches, families, and friends–a Malleus Malleficarum for our times

Dave

*I think Jonathan Pageau makes some good points here about the validity of the so-called “Evil Eye,” tradition, derided by some materialists.

**I have heard some suggest that those out of work should get checks from the rich/the government, and so what’s the problem? This strikes me as not ‘progressive’ in any sense. What about the ‘dignity of labor’ so hallowed by the Marxist tradition? I find the ‘just give them a check and they should be happy’ mentality degrading and paternalistic. Perhaps it is necessary–but don’t dismiss the cost to the soul.

^A brief parody of Kraemer and Sprenger (with all references entirely made up)

There are many who say that we should not wear masks in public. For has not Aristotle said in his Physic that, “to one is one thing, and another, like unto it, has the same properties” (B.V-8.12). So we see that all things “come unto all other things” (Averroes, De Civitate, Q. 12, p.4, S.4), so then it follows naturally that we follow The Almagest and declare that we maintain the motion of the “heavenly spheres,” which in this case means, our bodies. For Ptolemy has said much that many of the wise would hardly dare to gainsay.

And should not our bodies be compared to the heavenly spheres? For Plotinus has called us all a microcosm of the worthy cosmos, as have many holy men, though others have not agreed (Quintus, et al, Deus Mirabilius, Book II, p. 8). And is not the face the “bearer of all things” (Isocrates, Etymologies Part II, 6.7.8)? We bear with one another, then, for how else shall we live if we bear not with another, as Ulfin stated in Amor Arondus Ibid (Bk. II, p. 5)?

But others deny it, stating along with Avicenna that, “As things move, so they are distinct, for not all motion is equal (Figures, Book V.3-1).” Now if motion is not equal, than it means that motion must be set in a hierarchy, and to appear contrarian is not in the habit of the scholar, who seeks to have “all put in its proper place (Fabius, Magnus Opus, Bk. 1.3).” . . .

commits two cardinal sins in my book when discussing the Medieval period.

commits two cardinal sins in my book when discussing the Medieval period.