I loved The City of Akenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and its People. I loved it even though I skipped large chunks of it,  and some of what I read went beyond my understanding. This may sound strange, but Barry Kemp’s work is such an obviously great achievement that it goes beyond whether I like it or not. All that to say, I do really like the book, and wish I had knowledge and the ability to follow him all the way down the marvelous rabbit holes he traverses.

and some of what I read went beyond my understanding. This may sound strange, but Barry Kemp’s work is such an obviously great achievement that it goes beyond whether I like it or not. All that to say, I do really like the book, and wish I had knowledge and the ability to follow him all the way down the marvelous rabbit holes he traverses.

The book puts a capstone on Kemp’s 35 years excavating the city of Amarna, a city built by Akenaten IV (sometimes known as Ikhneton). Akenaten has long fascinated Egyptian scholars, mostly because of his religious beliefs. He departed from the religious beliefs that dominated Egypt for centuries and clearly attempted to change the religious landscape of Egypt in general. He may have been a monotheist, which adds to the potentially radical nature of his rule.

Differing interpretations swirl around his time in power, as we might expect. Some like to view him as a great rebel against the constraints of his society. Some view him as a great religious reformer. Today, given the overwhelming influence of tolerance, the mood has switched to seeing him as a tyrant and usurper. I hoped Kemp could help sort out some of these dilemmas. His book reveals much, and also creates more mystery at the same time. After reading we get no absolute conclusions. Usually when authors do this I get frustrated. But in Kemp’s case, who can blame him? The historical record is 3400 years old.

But before we get to this, Kemp and the publisher deserve praise for the aesthetic aspects of the book. It feels good in your hands. It has thick and glossy paper. The text and numerous illustrations mesh very nicely. The book has an almost ennobling quality. You feel smart just looking at it.

I also have to admire Kemp’s style. If I had spent 35 years in excavations at Amarna and then wrote a book it would almost certainly have a shrill, demanding tone. “I spent all this time here and now you are going to look, see, and appreciate it all!” But Kemp writes in a relaxed, thoughtful manner that seems to say, “Ah, how nice of you to drop by. If you’d like, I have something to show you.”

So many kudos to Kemp.

But now on to Akhenaten himself.

What was he really trying to do, and how did he try and accomplish it?

Clearly Akenaten wanted something of a fresh start for Egypt. He moved his whole seat of government and started building a new city called Amarna. In Egypt’s history this in itself was not all that radical, and other rulers have done something similar, notably Constantine with “New Rome.” Unlike “New Rome”/Constantinople, however, Amarna appears to be way off of Egypt’s beaten path. This idea in Egypt means something different than it might for us, as nearly all of life got compressed within a few miles of the Nile. Even so, Akenaten chose a place rather out of the way by Egyptian standards, perhaps the equivalent of the U.S. making its new capital Des Moines.

Perhaps Akenaten didn’t just want a fresh start, he wanted a totally clean slate upon which to build, free from all outside interference (shot from British excavations in the 1930’s below).

So he was a radical, then?

Perhaps, but in building a city, how radical could one be? Most cities tend to look like other cities. He faced limits of resources and experience. So Amarna looked like most other cities, but a few subtle differences might reveal a lot.

For example, the builders made the entrance to the “Great Aten Temple” much wider than usual temples, so wide that one could not envision doors ever being present. This may mean nothing other than they ran out of material. But interestingly, most city-dwellings had this same open feel to it. In great detail Kemp describes how the houses in the city had few boundaries. Slaves, officials, and commoners would use the same pathways in and out of the same houses.

Kemp also mentions that the plain of Amarna itself presented itself as very open and flat.

No conclusion forces itself as definitive here. We can say that,

- Most places in Egypt had a similar geographic layout to Amarna

- The houses may have been constructed in an ad-hoc fashion due to lack of resources or time

- Maybe Akhenaten wanted a really open feel to the front of the Great Temple, but that may not have any particular connection to anything else. Or maybe they had a plan for very large, ostentatious doors that never got realized.

Or perhaps we should see intentionality in all these elements. And if intentionality is indeed present, what might that reveal that he really did have a grand vision for real change in Egyptian society.

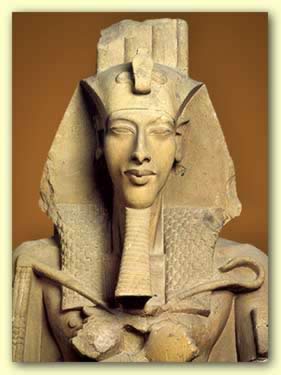

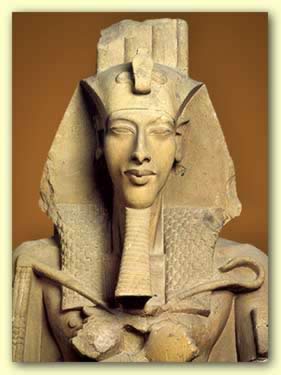

Another intriguing problem deals with Akhenaten himself. The most famous statues linked to him and his reign look generally like this:

This one makes him look more thoughtful and perhaps more humanized

Both statues reveal an intense and thoughtful man, given to much introspection. Or possibly, obsession? Kemp points out that the offering tables in the temples stood much larger than those in other standard Egyptian temples. Was he consumed by an idea, or a Reality? His faces here perhaps reveal just this.

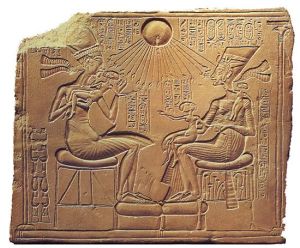

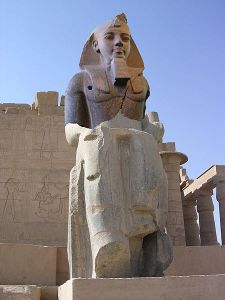

And yet, it is entirely possible (though far from certain) that he actually looked like this:

What should we make of this?

One possibility is that the last image is not of Akhenaten at all, and this solves the riddle by eliminating it. But Kemp thinks this last sculpture to be an accurate portrayal of what he really looked like. I’ll go with the guy who spent his life studying the ruins.

So if he portrayed himself differently than he actually looked, it must have been a propaganda tool of manipulation?

No, Kemp thinks not. Pharaoh’s often had the moniker, “Lord of the Appearances.” They would be seen by people often, even commoners. And this would likely be all the more true in the isolated and not terribly large city of Amarna. Besides, the statue directly above dates from Akhenaten’s time and surely was “official” and not black market. Kemp often cautions us not to look for consistency in Ancient Egypt, or at least our modern and Greek influenced sense of consistency.

Kemp suggests that the image Akhenaten projected may have had to do with his role as teacher of righteous living. Certainly it seems he viewed himself this way, and others did too. This may not make him a prig necessarily, because it was a role Pharaoh’s often assumed, perhaps as a matter of tradition. The austere intensity of the first two busts (at least 6 ft. high) help confer the image of a deeply felt inner life that he wanted to communicate. And since the Egyptians loved visuals more than the written word, his busts carry his theological message.

I didn’t buy the modern, “Akhenaten as a religious tyrant” argument before reading the book, and I think Kemp indirectly argues against this. For one, we find small statues of other gods in scattered Amarna households. Their houses were small and the statues of normal size. Given the free-flowing nature of Amarna neighborhoods, other citizens would easily know about the statues. For Akhenaten to have no awareness of these gods would mean that he had no secret police, no informants, and this speaks against the possibility of ‘tyrannical rule.’ He almost certainly knew about the gods, and tolerated them, however grudgingly.

Or perhaps he actually wasn’t a monotheist? But then, how radical could he have been? Or perhaps he had strong views and wanted wholesale change but approached the issue pragmatically. Neither option gives us a Stalin-esque tyrant.

Other curious details make me lean away from the “tyrant” position. Cities designed before Akhenaten had rigid layouts and exacting aesthetics. But as Kemp writes elsewhere, “Most of this city was built around a rejection of, or an indifference to, a social prescription and a geometric aesthetic.” Instead, “organic harmonies” and “personal decision making prevail instead.” My bet is that Akhenaten may have been too consumed with his religious ideas to really be a tyrant even if he wanted to.

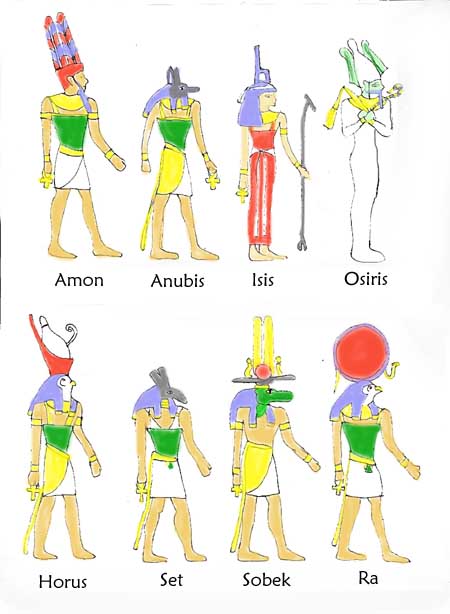

Akhenaten seems to have had a “smart-bomb” approach to religious reform, at least politically. His main innovation/change might appear slight to some of us. The Egyptians depicted their gods in at least partial human form.

But over and over again, Akhenaten depicted himself only with Aten, and in these images, Aten has no quasi-human form. The sun itself sufficed for him.

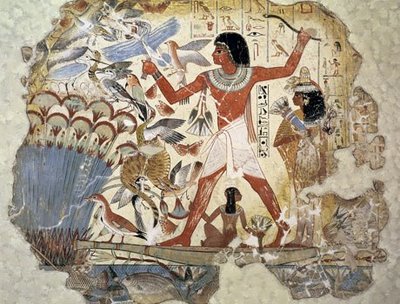

And this image from the Aten temple . . .

So perhaps in this area we see clarity of vision and consistency of follow-through, as to what it means, I don’t know. It fits, though, with his overall theme of simplifying religious belief.

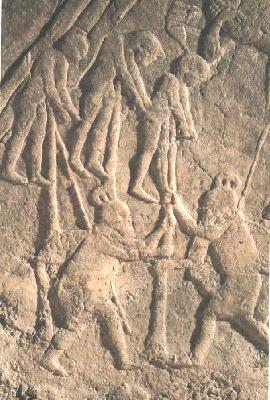

Kemp shows us that Akhenaten worked hard at cultivating the image of a good life at Amarna. Many wall murals show him as a generous provider and consumer of goods. Excavations reveal that this may not have been entirely propaganda, but Kemp reminds us Akhenaten reigned during a prosperous and secure time in Egypt. But in 2006 excavators discovered a series of tombs for commoners that reveal high incidents of early childhood death, malnutrition,or skeletal injury. This could throw us right back to the Stalinist image some have of him. But the high incidents of childhood death could reveal an epidemic in Amarna, which would spread rapidly in its densely packed population. Hittite records tell of a plague that spread from Egyptian prisoners of war during Akhenaten’s time. As to the injuries, I can’t say whether or not this is typical for when new cities get built. Akhenaten may have harshly driven the people to work harder and more dangerously than normal, or it may have been par for the course with ancient construction projects.

The insistence on building a new city may reveal an element of monomania, but certainly other pharaohs did the same thing. The pyramid builders demanded vastly more labor from their people/slaves. Besides, Akhenaten had many critics within Egypt after his death, but no one blamed him for building a city. This fit within the normal roles pharaohs played.

Akhenaten likely saw himself as a religious liberator of the people. I see a man with a purity of vision, but also a pragmatist in good and bad ways. He possessed great intelligence and valued introspection. I see him dialoguing with himself, along the lines of, “I want ‘x.’ But the people only know ‘y’ and expect ‘y.’ So I will try and lead to them to ‘x’ through a modified version of ‘y’ — not to say that I hate everything about ‘y’ — just some things.” If I’m right, this inner wrestling match would lead to inconsistency and confusion in his own mind. Perhaps he lost his way a bit. “I must have a nice new city to show the people the greatness of the truth,” or something like that.

Or maybe not. I wish I knew more. Akhenaten provides a great template for a historical novel.

Perhaps he went too far, but I do think he had good intentions. Of course much evil gets done with this mindset. We all know where the road of “good intentions” leads. But it’s hard to say for certain what evil he actually did. But he did seek to remove certain key beliefs about the afterlife. The traditional Egyptian’s journey to eternity had many perils and thus required many charms, protections, and so forth. All this gave a lot of power to certain priests. Akhenaten’s tomb stands in marked contrast to almost all other kings for its simplicity. Clearly he sought in some ways to “democratize” death in his religious beliefs. I think that Akhenaten wanted to simplify things in general for the common man. But then again, his tomb contains other traditional pieces, such as the “shabti” — special figures designed to do conscripted labor in the next life. So even the intense, focused Akehenaten either conceded to some traditional beliefs or really believed these apparently inconsistent ideas.

The mystery of Akhenaten continues.

We know that his religious ideas more or less died with him, and indications exist that foreshadow this even during his lifetime. Very few people changed their names to reflect the new ‘Atenist’ belief, and this we know from the many tombs in the area. Had his beliefs caught on the switch in names would have also, as happened at other times in Egyptian history. The narrative that we naturally accept about his attempt at religious change sounds similar to this text from Tutankamun, who may have been his son.

…the temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine as far as the Delta marshes . . .were fallen into decay and their shrines fallen into ruin, having become mounds overgrown with grass . . . The gods were ignoring this land. If an army was sent to Syria to extend the boundaries of Egypt it met with no success at all. If one beseeched any goddess in the same way, she did not respond at all. Their hearts were faint in their bodies, and they destroyed what was made.

But Kemp shows that the above text doesn’t reflect the truth. Akhenaten kept open most all the temples in the land, and left his reforms for Amarna. And as we’ve seen, he apparently let the worship of other gods go on unofficially even in Amarna itself. So if Akhenaten engaged in political hocus-pocus (and maybe he didn’t) then at least two played that game.

So by the end of the book we arrive where we started. But Kemp’s extraordinary archaeological skills take the reader as far as they can go. From here on, one must take a leap into the realms of poetry, which is where History really belongs.