Greetings,

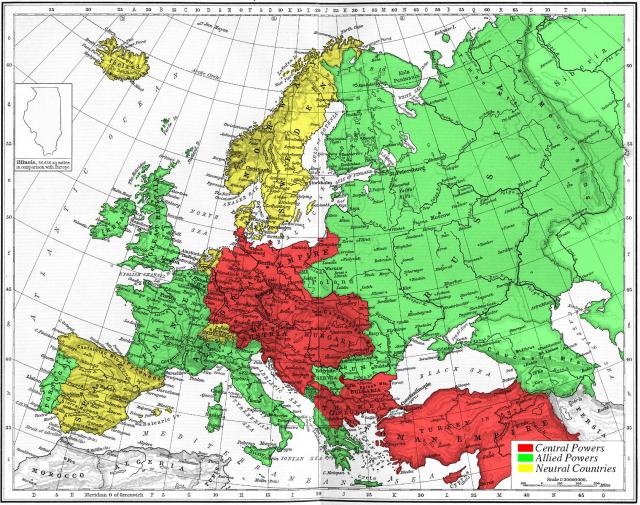

This week we began the fighting in World War II, which in many ways simply continued World War I. It had many of the same combatants on nearly identical sides, but the stakes had increased as weapons got more powerful, and the ability of governments to mobilize their populations got stronger. We looked at the fall of France, and the idea of blitzkrieg in general.

I believe that many false assumptions exist as to why France collapsed catastrophically in May-June of 1940. Among them:

Among them:

- That France was ‘defeatist’ throughout the 1930’s, so when war came, they laid down and died for Germany.

On the contrary, they spent the 1930’s building up their armed forces, believing a conflict with Germany inevitable. They had more modern weapons than Germany did, in general.

- That France wrested strategic control from England, who had more “backbone” than the French.

On the contrary, France throughout the 1930’s pandered to England at their own cost, and adjusted their tactics to protect Belgium, and hence, England itself. As I mentioned in an earlier post, England had much more to do with the “appeasement” of Hitler than the French.

- That France was purely defensive minded, and never fought.

Again, not so fast. They did go on the offensive (mistakenly) in Belgium, and they did suffer some 200,000+ casualties in their six week conflict with Germany.

The Germans shocked them through their swift movement through the Ardennes Forest, a terrible miscalculation by France. But when the Germans broke out of the Ardennes the English decided to ‘abandon ship.’ In English lore the Dunkirk evacuation was a heroic moment of pluck and glory. For the French, the English cowardly abandoned them in their hour of greatest need.

Well if these are not the reasons, why then did they collapse so dramatically? No one in Germany, not even Hitler, believed that they could accomplish what they did so quickly? We have to dig deeper.

France had the military tradition in the whole of Europe. From Charlemagne, to Wiliam the Conqueror, to Joan of Arc and Napoleon, no one could match the French fighting reputation. In W.W. I they lived up to this reputation. About 10% of their country suffered untold physical devastation. French soldiers suffered in greater percentages than any other main combatant, yet still they emerged victorious.

Victorious, yes, but also exhausted. The idea of France suffering what it did before could not be comprehended. It must never happen again. This mindset led to the elevation of the army in the national consciousness. It became their crown jewel, set apart from the rest of society. “The army will save us.” One sees this in tangible ways, such as French military HQ’s not even having direct phone lines to government leaders. “You want to talk, you come to us.” It manifested itself more directly when the Nazi’s invaded. After the British left at Dunkirk, Marshal Petain wanted to surrender, at least partly to make sure he could “preserve the French army,” France’s “my precious” (to channel Tolkien’s Gollum).

Understandably, the French did not want to fight the Germans in France. So they built the Maginot Line, a vast network of forts along the French-German border. And, they planned an offensive into Belgium to meet what they assumed would be the focal point of the German assault, just like it was in W.W. I.

Understandably, the French did not want to fight the Germans in France. So they built the Maginot Line, a vast network of forts along the French-German border. And, they planned an offensive into Belgium to meet what they assumed would be the focal point of the German assault, just like it was in W.W. I.

But the Germans did not plan their main assault there. Instead they went through the Ardennes Forest, where France had their weakest troops.

This was not merely bad luck. The French suffered from what many victors suffer from, a belief that the next war will be like the last. Their key miscalculation was in the area of tanks. In W.W. I tanks served as support, and not as spearheads. But thanks to Heinz Guderian, the Germans thought of how to use tanks differently, in mass formation, not spread out like field kitchen units. The Germans thought differently in part because they had to. Nothing prevented the French from coming to Guderian’s conclusions, except their own short-sightedness.

We must also consider the nature of blitzkrieg itself, which sought to hit quickly and without mercy or pause. The idea arose from the concept that the Germans knew that they would be outmanned and outgunned in the coming war. Victory needed to be quick if it was to come at all. They stunned the French and never let them get their bearings.

Blitzkrieg also seems to fit with the mindset of the Germans, and also the Japanese. Both sides felt humiliated by other western powers. Both sides dealt with pent up anger for at least several years before they actually attacked. ‘Lightning War’ allows you to vent all that anger in one go, so to speak.

But one wonders if the dramatic and complete nature of Germany and Japan’s early conquests did not work against them eventually. The amount of territory they gobbled up gave them the dilemma of occupation. How should they pacify their holdings? They could have made friends and tried to integrate with them (as the Romans or Persians might have done), but Nazi and Japanese racial theories made that a non-starter, with the embarrassing exception of Vichy France. The only way then to secure peace is to ‘beat-down’ the opponent to such a degree that they could not resist. But blitzkrieg meant quick pincer thrusts to stun the opponent. It was not a tactic geared towards controlling territory, but to destroying armies. But if you want to ‘beat-down’ the opposition, that requires more force, which requires more resources, which might also inspire more resistance in the end.

But I think another issue at stake is the relationship between totalitarian ideologies (present in both Germany and Japan) and its relationship to the individual, something I touch on in this post, if you have interest. Totalitarian society’s absorb individual identities into something larger, more abstract. Maybe it’s  the “German Race,” or “Japanese Honor,” or “The World Wide Class Revolution,” in the case of communism. Whatever the cause, the individual subsumes themselves to the group. Totalitarian movements have real appeal in part because they offer us something outside of ourselves. After all, what could be a greater form of pride than having oneself be the only reality?

the “German Race,” or “Japanese Honor,” or “The World Wide Class Revolution,” in the case of communism. Whatever the cause, the individual subsumes themselves to the group. Totalitarian movements have real appeal in part because they offer us something outside of ourselves. After all, what could be a greater form of pride than having oneself be the only reality?

The danger comes when you reach beyond yourself and attach to something that denies and robs you of your individual identity. You graft yourself onto a leech that seeks to erase your uniqueness, your spiritual identity.

Destruction of the spiritual identity of the person is a mere precursor to the destruction of the physical person itself. In the case of the Nazi’s they certainly did this to Jews, Gypsies, the handicapped, etc. But some Nazi’s did it to themselves in the end. One sees in Hitler, the S.S., and the Japanese Kamikaze’s (to name a few) a worship of death itself, a will towards destruction. I don’t want to hang too much on my non-existent ability to play arm-chair psychologist, but I wonder if subconsciously they courted their eventual destruction with their military strategy. For blitzkrieg was a strategy rooted in anger and desperation. It could not have long-term success, but gave one the exaltation of a “last stand,” a glorious death.

And this brings us to what may be the real roots of Japanese and German strategy. Both countries espoused ideologies that looked to a distant past for inspiration, and sought some form of purity. In other words, both had a strongly romantic strain. The romantic loves the grand gesture, and as an idealist, does not think about results. The Japanese looked towards the bygone era of samurai’s, who lived for glory. The best way to achieve glory was death in battle. The Nazi, as we discussed a few years ago, had direct inspiration from Wagner, where someone is always dying or something is always burning in the end. But from this death could come rebirth.

Many 19th century romantic poets had a fascination with death, as did their progeny (think Jim Morrison, for example). Did the Germans and the Japanese plan a strategy that subconsciously they thought would fail? Did they seek glorious death instead of victory?

I do not mean to imply that “Romanticism” is bad, any more than idealism is bad. In literature one only needs to think of C.S. Lewis’ Reepicheep the mouse to see romanticism oriented in positive ways. But we should consider the possibility that there may be a reason why military strategists shake their heads at German and Japanese strategy in the war. It did not make much sense, and maybe they did not want it to.

These dilemmas would prove the undoing of both Germany and Japan.

Finally, thanks to The Toynbee Convector, I stumbled upon this death oriented totalitarian movement, if you are interested.

Many thanks,

Dave