“Da quod iubes, et iube quod vis.” – Augustine

Martin Luther distinguishes two genera in scripture: Law and Gospel. When God speaks command, threat, accusation, and judgement, there we hear Law. When God speaks gracious promise, there we hear Gospel. Luther understood the primary purpose of the Law not to be condemnation, but evangelization: the Law drives us to the Gospel, where we find God’s gracious promises. The law kills us spiritually–we cannot obey God’s commands and so suffer under his judgement–so that we hear and believe God’s gracious promise of new life in Christ.

Law is about what we do (or don’t do). Gospel is about what is done for us and to us. Rather than thinking about our students working on assignments we could think about assignments working on our students.

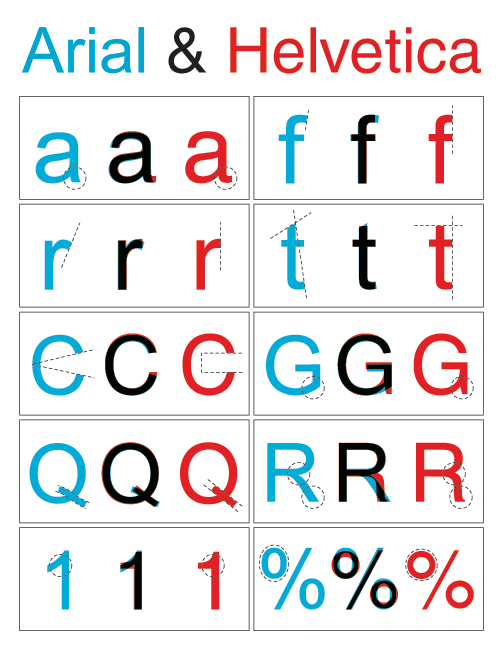

The language of grading is assuredly that of Law. Grading begins with commands, which we call “assignments”. Work out problems 25-45, odds only. Write a short essay discussing Christian iconography in Melville’s Billy Budd. Be ready for a quiz on the Krebs cycle tomorrow. Threats accompany the commands: 10% will be deducted for each day the paper is late. No one may graduate without completing the Senior Thesis. No makeup examinations will be given. Blood red accusations spatter the work: -0.5; not in the simplest form. You need to better support your argument here. France is not located in the center of Africa! Judgement concludes the business of the assignment: A-; good arguments, but your introduction was rushed. F; so sloppy as to be unreadable. 82%; somewhat improved.

The parallels between the language of Law and the way we communicate to our students when we grade are striking. What effect does this sort of language and communication have on students? Here too, Luther’s ideas about Law are instructive.

Luther describes the civil use of the Law: Law restrains sinners from (some of) their wicked behavior. The Law tells us that if we murder, we are God’s enemies and he will condemn us. Fear of that retribution might motivate one not to murder, which is assuredly a good thing. Fear, though, is powerless to form souls to desire and love truth. Indeed, because we cannot uphold the law, it spiritually kills us. The righteousness that fear of the Law compels is not the righteousness of Christ. Refraining from murder out of fear (even though we still want to murder!) does not create in us a heart that loves God. By analogy, some students have no desire for truth, for learning. Grading-as-Law serves to restrain their wickedness through fear in a way similar to God’s Law.

Grading-as-Law, though, kills the desire to learn. On the one hand, a student who repeatedly fails and is subject to the judgement of bad grades may be so dispirited that he abandons the hope and pursuit of knowledge as unattainable. The lament that “school is stupid” is a symptom of this sort of intellectual death. Even more spiritually dangerous, the student who says, “tell me what I have to do to get an A” has also suffered a kind of intellectual death. Like the Pharisees (or the elder son in Luke 15), he has abandoned the pursuit of living knowledge for a sterile and ultimately fruitless obedience.

What would it look like if we preached not only Law, but also Gospel to our students? To do that some of our assignments would have to be designed and communicated in such a way that they do work on the students, not the other way around.

First, we must believe that what we teach, while not perhaps the summum bonum, is nevertheless a bonum, valuable in its own right. What that means is that if students neglect an assignment, they deprive themselves of the good that assignment would do to them. If they undertake an assignment, it should do work on them such that they’re a subtly changed person for having completed the assignment.

We need to be able to articulate (to ourselves and to students) what work we expect an assignment to do. Our assignments are doing work on our students, but I often think we don’t have a sense of what work they’re doing. If we have our students do needless busy work, that’s forming their minds and souls. But in a way we want? No.

I suspect this can lead us to talk about assignments differently (exercise might be a good metaphor; physical exercise does work on our bodies the way academic exercises should do work on our minds) and to offer different exercises than we do now. And to communicate about them differently too.

Maybe the best way to talk about Gospel in the sense that I mean it here is to offer up an example. I suspect I have one from my physics class, but I’m hesitant to share it. The exercise requires enormous secrecy to work correctly. It’s risky, but I think it can be formative.

When my physics students, a mix of eleventh and twelfth graders, walked into class on the first day, they found index cards spread out on the tables with names. The students sat and I took back up the cards. These were the assigned seats. The class went about its business. The next day, the students found that the cards as before, but each student had a new seat. They sat, I collected, class proceeded. This went on for a week. Different seats every day. Some students asked about it. I just shrugged and kept teaching. They furrowed their brows.

After a week, the cards stopped appearing. Instead, the students would sit and I’d move some of them to other seats. This repeated itself daily. They started to get frustrated. They asked what was up. I got questions from parents. I got questions from colleagues. I kept shrugging.

After a month, one fine young gentleman came to class and said, “I think there’s structure. There’s a pattern!” I shrugged, ignored him, and taught class. And every day students had to move.

That young man and a few young ladies got a notebook. Every day they wrote down who sat where. When they were going to miss class, they made sure someone else took notes. I ignored them and looked puzzled when people asked about it.

A few more weeks passed. One day I walked into class and didn’t have to move any students. I raised an eyebrow, said nothing, and went to the grocery store after class to buy cake and donuts. I wasn’t sure, but I was hopeful.

The next day, everyone sat in the right seats again. I stopped class, and asked what was going on. They’d been testing different patterns for a couple of weeks at that point, and finally hit on the one I was using. They were coordinating with everyone, who sat where before class to see who I’d move. Finally they had it. We had a party in class. From then on they could sit where they liked. (For us math nerds: the algorithm to figure out who sat where was a modular addition scheme by numbered seat such that the pattern repeated about every 17 days. This was really hard to suss out. They originally thought it was a day of the week thing, and seeing that it wasn’t took a decent sized chunk of data.)

So, what was I doing, besides convincing the students, their parents, and my colleagues that I’d gone off my rocker a bit? I wanted them to experience what it meant to be a scientist: having faith that what seems chaotic is ordered, believing that we can fathom that order, collecting data, wrestling with doubts, formulating theories, testing them, and finally enjoying the fruits of their labor.

When they finally understood the seemingly arbitrary pattern, we had a long talk about what it meant to be a scientist. If they got nothing else out of the class, they got to be scientists and see actually science at work. It was visceral.

It could have gone wrong in a hundred ways. It was an exercise whose effect depended on the students not knowing it even existed. I could have lost my poker face and hinted that there was structure. I could have told a colleague who blabbed. They could have given up in disgust and suffered the bizarre seating for the year. A few could have figured out what was happening and not shared it with their friends. They could have randomly sat in the right seats without understanding why. I could have messed up their data by mis-seating someone (this scared me; it’s hard to follow a pattern precisely while seeming to behave arbitrarily). The exercise could have failed in a million ways, none of which would reflect any fault in the students.

Wrestling with their seating chart did formative work on the students. Just a little bit, it changed the way they saw science and the world around them. It was the best teaching I ever did. And there’s absolutely no way to grade it.

Ok, perhaps we see a bit of rote copying in terms of the motorcycle and the leather, but still, who wouldn’t want to be that guy?

Ok, perhaps we see a bit of rote copying in terms of the motorcycle and the leather, but still, who wouldn’t want to be that guy?

Lewis: “Yes and no. There is a difference between a private devotional life and a corporate one. Solemnity is proper in church, but things that are proper in church are not necessarily proper outside, and vice versa. For example, I can say a prayer while washing my teeth, but that does not mean I should wash my teeth in church.”

Lewis: “Yes and no. There is a difference between a private devotional life and a corporate one. Solemnity is proper in church, but things that are proper in church are not necessarily proper outside, and vice versa. For example, I can say a prayer while washing my teeth, but that does not mean I should wash my teeth in church.”