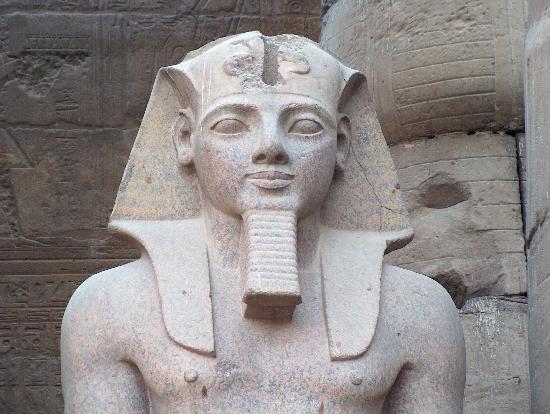

Whenever I teach about ancient Egypt that civilization always impresses me with its “weight.” I mean that the Egyptians expressed an utter confidence in the meaning and purpose of their civilization. We see evidence for this in a variety of places, but I draw attention to the “Tale of Sinuhe,” one of the more beloved early Egyptian folktales. The story recounts some impressive adventures of Sinuhe abroad, but the climax of the story is not found there. Sinuhe triumphs when he returns home, when he receives the favor of the king, and (strange to our ears, no doubt) when the king grants him a lavish tomb. The story concludes,

There was constructed for me a pyramid-tomb of stone in the midst of other pyramids. The draftsmen designed it, the chief sculptors carved in it, and the royal overseers made it all their concern. Its necessary materials were made from all precious things one desires in a tomb shaft. Priests for death were given to me. Gardens were made for me just as is done for the highest servants. My likeness was overlaid with gold. His majesty himself made it. There is no other man for whom the like has been done. So I was under the favor of the King’s presence until the day of death had come.

All Sinuhe ever needed was in front of him the whole time, a Hallmark card ending if there ever was one.

Of course the Exodus dramatically and deservedly shook this confidence,* and at times the “weight”and “presence” of Egypt would no doubt feel oppressive and claustrophobic (as it does for me with the Great Pyramid of Giza), but, nevertheless, they had a marvelous run.

Recently reading a collection of tales from medieval Russia, I had a reaction not unlike the one I have with Egypt. Russia is different than America — obviously. But how so? A quick look at literary luminaries reveals much. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn undoubtedly deserves its high praise, but then one reads The Brothers Karamazov (roughly contemporary works) and discovers something entirely different. Twain bounces here and there and constructs a fanciful lark (for the most part) out of the idea of rebellion against society. Though he is thoroughly American, there remains something of the delightful English politeness about him, making his points in circuitous fashion. Dostoevsky writes from a much more solid, earthy foundation. The “earthiness” of his foundation gives it all the more spiritual impact. He writes not of ideas at all — except to criticize them and the very concept of “ideas.” Instead he comes from a place of absolute confidence in a particular reality. In his stories the rebels are the bad guys, who try and introduce discontent into the Russian soul.

Just as we have no particular historical roots as a nation, so our folktales take on a whimsical character and have no particular roots in history (i.e., Paul Bunyan, Johnny Appleseed, etc.). Even when Twain makes his best points, they take the form of jokes. Dostoevsky . . . not so much.** So Russian folktales usually seem to have much more direct historical roots and could rarely be described as “whimsical.”

In the tale told of about the Polish king Stephen Bathory’s siege of the Russian town of Pskov (ca. late 16th century) we see all of these characteristics. It speaks of “Holy Russia” without a trace of irony. When the “pagan” king’s army advances past some of the outer defenses, the story turns:

. . . in the Cathedral of the Life-Giving Trinity the clergy incessantly prayed with tears and moaning for deliverance. . . . [they] began to weep with loud voices, extending their arms to the most holy icon. The noble ladies fell to the ground and beat their breasts and prayed to God and the most Pure Virgin; they fell on the floor, beating the ground with their heads. All over town women and children who remained home fervently cried and prayed before holy icons, asking for the help of all saints and begging God for the forgiveness of their sins . . .

After an extended poem on the power of God the tide turns, and the people rally. But they need to stem a breach in the defensive wall.

. . . [the Russian commanders] ordered that the icons be brought to the breach made by the Poles. Once the holy icon of the Holy Virgin of Vladimir had protected Moscow at the time of Tamerlane. Now another was brought because of Stephen Bathory . . . and this time the miracle happened in the glorious city of Pskov, . . . for divine protection invisibly appeared over the breach in the wall. . . . All the commanders, warriors, and monks cried out in unison, “O friends, let us die this day at the hands of the Lithuanians for the sake of Christ’s faith and for our Orthodox tsar, Ivan of all the Russias!

In his marvelous, Everyday Saints, Archimandrite Tikhon of the Pskov Caves Monastery related a story about a particular bishop caught in an unfortunate position amidst a large crowd. Uncertainty reigned in Moscow in a public square during the collapse of communism in the early 1990’s. Some soldiers came over to shield the bishop from the crowd and began to take him into their vehicles for protection. Many in the crowd, however, thought the soldiers were imprisoning the bishop. The Archimandrite relates that several people rushed out towards the bishop, saying, “It is happening again [i.e., the Communists imprisoning church officials]! This shall not be! Come brothers, let us help this good priest. Let us die for him!” Soldiers dissuaded them from hurling themselves on their bayonets only by careful explanation of their purpose.

A particular sense of reality is evident, and an absolute confidence.

Our heroes play different roles. Even the golden age of Hollywood, when America supposedly bursted with confidence, gave us heroes like Humphrey Bogart — a man “in the know,” and somewhat detached. We love the reluctant hero.^ Russians remember instead princes like Alexander Nevsky, who when attacked by the Swedes, supposedly went immediately to church, where

remembering the song from the Psalter, he said: “O Lord, judge those who offended me. Smite those who set themselves against me, and come to my aid with arms and shields.”

Before his death, Alexander took the most strict of monastic vows, the “schema.”

Alexander’s reaction today could only be mocked by the west, just as Putin’s physicality — be it swimming in icy lakes or wrestling tigers, or whatever — becomes late-night fodder. But Putin, consciously or not, sincerely or not, very likely taps into something deep within the Russian soul and Russian history — the fearless leader of absolute confidence with not a trace of detached irony.^^

Those who do not like President Obama sometimes don’t see that his appeal has little to do with his policies. Rather, he embodies a certain idea of American hip culture. He tells deprecating jokes with wry humor, a wink, and a nod. He appears on Marc Maron’s podcast and Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee with Jerry Seinfeld. So too we in the west, I think, fail to understand Putin’s popularity. Perhaps he channels Alexander Nevsky, not Humphrey Bogart.^^^

Dave

*I favor a late Exodus date, and so see Ramses II as the beginning of the end, and not an “Indian Summer” after the decline had already begun in earnest.

**Of course Dostoevsky can sometimes be very funny. I laughed aloud at various points in The Brothers Karamazov, and The Gambler. But Twain was known as a humorist, and while the idea of Dostoevsky as a one man show is funny, the show itself . . . would not be.

^Might Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt of the Mission Impossible movies serve as an exception? He has none of the smirks of a James Bond. Hunt “believes” — believes in what? Who knows? Who cares? We don’t watch the movies out of love for the Ethan Hunt character, but for the stunts, scenario’s, etc.

^^The Archimandrite Tikhon has been involved with some controversy and mystery due to his “relationship” with Putin. An excellent interview with him is here — recommended. The interviewer represents a typical western perspective and the Archimandrite shows that he is not a modern-westerner. We should realize that a) Putin may have a sincere religious faith, and b) St. Petersburg will not orient Russia in the way that Peter the Great or other westerners might wish.

^^^Russia has experienced a dramatic rise in religious affiliation since the communist collapse, but not a corresponding rise in regular church attendance, at least according to one Pew Research study. I don’t mean to suggest that Putin faithfully believes and practices like Prince Alexander. If left utterly detached from the Faith, Russia’s earthiness will become frighteningly barbaric. As many have noted — Russia is a land of great sinners and great saints.