Barbara Tuchmann’s The Guns of August discusses the controversies, dilemmas, and human drama in the days leading up to World War I. She puts a special focus on the war plans developed by France and Germany in the years leading up to the war. The two plans reflect much about the two nations. Germany’s Schliefflin Plan

- Relied heavily on rail transport with precision timetables

- Relied heavily on heavy artillery and all of the other goodies of industrialization

- Involved violating Belgian neutrality, but no matter–the winner would determine the post-war narrative, and they had to go through Belgium to make their plan work.

France’s Plan 17 relied

- Heavily on initiative in the field for individual commanders, with the emphasis on attack

- Much more than Germany on the human element, “men win wars, not machines,” and so on–what the French called “elan.”

- They eschewed heavy artillery, feeling that it would slow their men down and give them a dependent mindset.

Both sides had perfect awareness of the other’s plans, and both thought the strategic situation favored their own side. The French, with their army in red pants, hearkened back to an older time. Some called for the uniforms to be replaced with a more drab color less visible on the spectrum. The French general staff refused absolutely. The red pants embodied the spirit and will of the army, a refusal to bend to the industrial spirit of the age.

Alas, German organization, artillery, and precision destroyed the French army in first weeks of the war, inflicting at least 250,000 casualties. France had to adjust, and while they managed to stave off disaster at the Battle of the Marne, the dash and the human initiative would fade away just like the red pants. They too brought out heavy guns and “succumbed” to the Germany way.

As events unfolded, both sides ended up digging into the ground for what became known as Trench Warfare, which characterized the fighting in the western front right through 1918. Historians usually offer a variety of explanations for this unusual development–neither previous or future wars would ever use trenches so completely.

- Some focus on the significant imbalance between defense and offense that existed between the western powers. Heavy weaponry for the most part had little mobility at this time, which limited offensive capability and gave an enormous advantage to the defensive.

- Some focus on the narrow geography between the German and French borders, which meant an extreme concentration of men and machines. More space on the Eastern Front, for example, meant some more mobility and much less trench digging.

These explanations have merit but I think miss the larger picture.

The triumph of the metric system presaged military developments in World War I. The old systems of measurements had its roots in human experience and proportion, i.e., the “foot.” or the “stone” (about 14 pounds), which would be local and based on the weight of an actual stone in a particular town or region. The new system greatly maximized standardization, minimizing locality, and made it easier to count, measure, multiply, and so on. In other words, the new system granted one more power.* The Industrial Revolution continued this standardization, which naturally granted increased power to produce goods on a mass scale

But all of this power came from literally digging into the earth to obtain the necessary raw materials for the engines of industry and war. As industrialization reached its peak manifestation, the soldiers too dug into the earth. Perhaps the eastern theater of war saw less trench warfare because it had less industrialization. It seems a curious symmetry exists between the birth of the modern war machine and trench warfare, and we should endeavor to explain it. In other words, the creation of industrialization (digging into the earth), and its apotheosis (trench warfare) mirror each other (in the picture of the soldiers above, change the uniforms and the men could look exactly like miners). For Europe, World War I ended the belief in the inevitable progress of mankind, represented by science/industrialization and democracy. One can easily argue that science and democracy (in the form of mass media, mass mobilization, and mass production) made the war much more deadly than any previous conflict.

We can begin by noting the symmetry between birth and death. Interestingly, many ancient cultures buried people in the fetal position, linking birth and death in a circle, which I discussed here.

Perhaps this should not surprise us, as birth and death have something of a symbiosis.

We see a similar symmetry in rock music. I grew up partially in the Grunge Era. I took great delight in the transition from 80’s pop to Nirvana and Soundgarden. But anyone who reflects for a moment should see something odd going on with music in the 1990’s. In his excellent book on that decade, Chuck Klosterman made two keen observations:

- The grunge attitude and aesthetic brought about the end of rock and roll. The whole foundation of rock music involved stardom, mass appeal, etc. Grunge artists had massive success while deriding, mocking, and hating that success, a kind of matter-anti-matter collision. In this sense, Kurt Cobain’s tragic suicide** can be seen as a harbinger, a death-knell for the genre as a whole. In many ways, the power that comes with stardom brings not life, but a kind of death, just as the power granted by industrialization ushered in an era of millions of deaths in war.

- What was with the litany of songs with large portions of lyrics devoted either to nonsense, mere sounds, or garbled unintelligibility?

We’ll get to that list momentarily. We saw something similar at the birth of rock and roll in the late 50’s-early 60’s, in the form of a variety of songs with nonsense/unintelligible lyrics that made their way into the American psyche.

- “Louie, Louie”

- “Wooly Bully”

- “Be Bop a Lula”

- “Tutti Frutti”

- Roger Miller’s “Chug a Lug” and “Do Whacka Do”

- Huey Piano Smith’s “Don’t You Just Know it.”

- And perhaps my favorite, the Trashmen’s “Surfing Bird”

All of these songs share the exuberance that characterizes the birth of an era. The nonsense, the invented sounds, reminds one of little kids discovering their mouths for the first time.

In the 90’s you have Klosterman’s list of songs with nonsensical and unintelligible lyrics. But this time, the tenor, and atmosphere of the songs embrace not the excitement of new life but chaos, meaninglessness, and death.

- Of course, Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” with Weird Al parodying the song’s unintelligibility.

- Blur’s “Beetlebum,” and “Song 2.” “Song 2” has a something of exuberance in it, but the video clearly shows it is the excitement of destruction, not creation. No coincidence then, that Paul Veerhoven used this song to promote his movie Starship Troopers, which parodied the meaninglessness of fascistic violence.

- Trio’s “Da Da Da.” Volkswagen used the song expertly to hint at the banality of life for young men. Leave it to the Germans, I suppose.

- Basement Jaxx’s “Bingo Bango.” Yes, the song has an upbeat mood to it, but the video hints at disorienting chaos.

- “Mmmmm Mmmmmm Mmmmmm” by the Crash Test Dummies. The song has beauty, but it is the beauty of an elegy. The group’s other hit, “Coffee Spoons and Afternoons” talks about receding hairlines, hospitals, drinking coffee in the afternoon wearing pajamas–not exactly the stuff of birth.

- At first glance, Hanson’s “Mmmmbop” may seem to have the stuff of “life” embedded within, but after listening for about 90 seconds, thoughts of anger, hatred, and despair flood one’s being. The song is hypnotically annoying/infuriating.

The end of rock music mirrored its beginning, but the mirror has cracks.

Historians date the birth of the modern state at different points. One can trace the beginnings in the later Renaissance, and things look more clear at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. But to see the state as we know it, with its bureaucracy, centralization, uniformity of law, and military organization, we have to look at Napoleon. We have a fascination with Napoleon for good reason–undoubtedly he embodied something romantic, something of promise, in his early years.

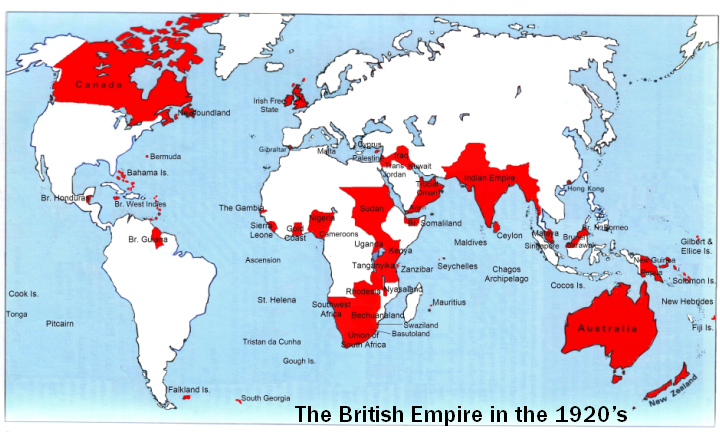

But 100 years later, that civilization, while having much more power at its disposal, actually approaches its death–a variety of historians (Niall Ferguson, Oswald Spengler) see World War I as the end of the west. Certainly at least, Europe–the core of western civilization– has never recovered from that conflict. Western civilization’s power and identity had its start with going into the earth in hope that its raw materials would give us power to establish Kant’s dream of perpetual peace. It ended differently.

Dave

*A variety of people have pointed out this connection between counting, numbering, and power. This may be why King David suffered such a strong rebuke when he took a census in Israel. He tried to count “excessively,” i.e., he tried to consolidate power inappropriately at the end of his reign.

**In an interview with Vulture magazine, Klosterman commented,

What is so profound about Nirvana is that the relationship ended up becoming real. The song “I Hate Myself and Want to Die.” The idea that a person who writes that song also does commit suicide — that is so on the nose. People would say things like, “If that guy hates fame so much, why doesn’t he just stop?” We did not fully believe that Kurt Cobain was actually unhappy. And then when he killed himself, it made that music suddenly weirdly true.

He was presenting ideas in a culture where irony was the central understanding of all messages, and he seems to have had no ironic distance at all. It actually was incredibly sad and depressing to him that people he didn’t like loved his music. It legitimately bothered him that, say, homophobes liked his music. It bothered him in a way that for other artists, it would’ve been seen almost as branding.

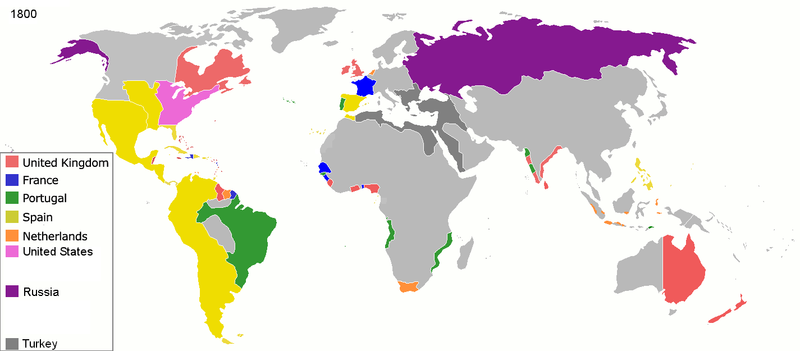

nd great wave of western exploration (the first being in the 15th-early 16th centuries via the Atlantic). Many hundreds of men risked everything for the sheer thrill of discovery, and yes, for the glory of it as well. In the early phases from ca. 1840-1860’s, most of this exploration seemed to me to have a generally innocent tinge to it. The more acquisitive imperialism came later.

nd great wave of western exploration (the first being in the 15th-early 16th centuries via the Atlantic). Many hundreds of men risked everything for the sheer thrill of discovery, and yes, for the glory of it as well. In the early phases from ca. 1840-1860’s, most of this exploration seemed to me to have a generally innocent tinge to it. The more acquisitive imperialism came later.