Many years ago I witnessed a debate between the Christian William Lane Craig, an atheist, and a Buddhist. Naturally I “rooted” for Craig, but also hoped for an interesting discussion. The atheist cut a poor figure. Craig possesses an enormous intellect and made quick and brutal work of the scientific materialist. In so doing, however, he neglected the Buddhist, who had a much more interesting argument, Though I disagreed with the Buddhist, I wished Craig had stopped shooting fish in the barrel and paid more attention to him. The Buddhist basically argued that values certainly exist in the world, contra the strict materialist. But he thought Christians too interested in the explanation for the values in the world–why not simply live in light of them? Craig never dealt with this enigmatic assertion.

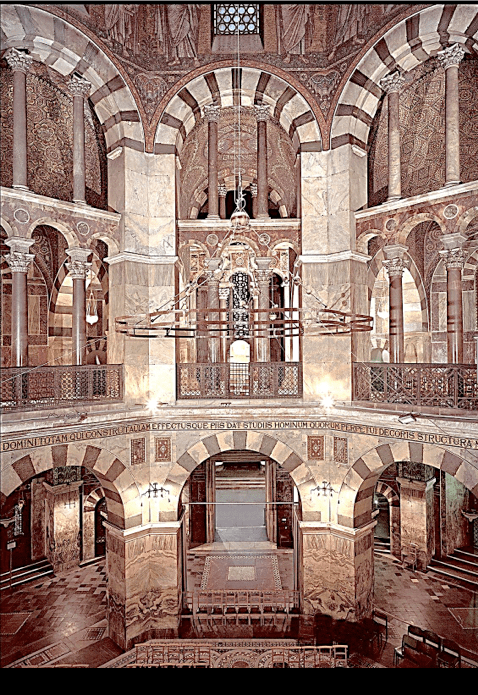

Everyone should read Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language, or at least glance through it as I did. 🙂 On its surface the book is about architecture, and he provides much directly for the professional builder. What makes the book remarkable, however, is how easily Alexander connects architecture to everyday life, and orients it not around outsized auteur individual creation, but making spaces for people to live communally and “normally.” To do so, one must tap into the “patterns” in everyday living. Though I know very, very little about Asian religious philosophy, I sensed something of the Buddhist or Taoist in Alexander. He felt no need to justify these patterns or explain their meaning. As far as I could tell he called mainly upon the intuition of our experience in presenting his ideas. Many have written about the increasing privatization of our culture, and no doubt this reflects itself in the buildings we create. Alexander injects a comforting warmth into our sterile sense of the meaning of a building, something quite needed given the state of modern architecture.

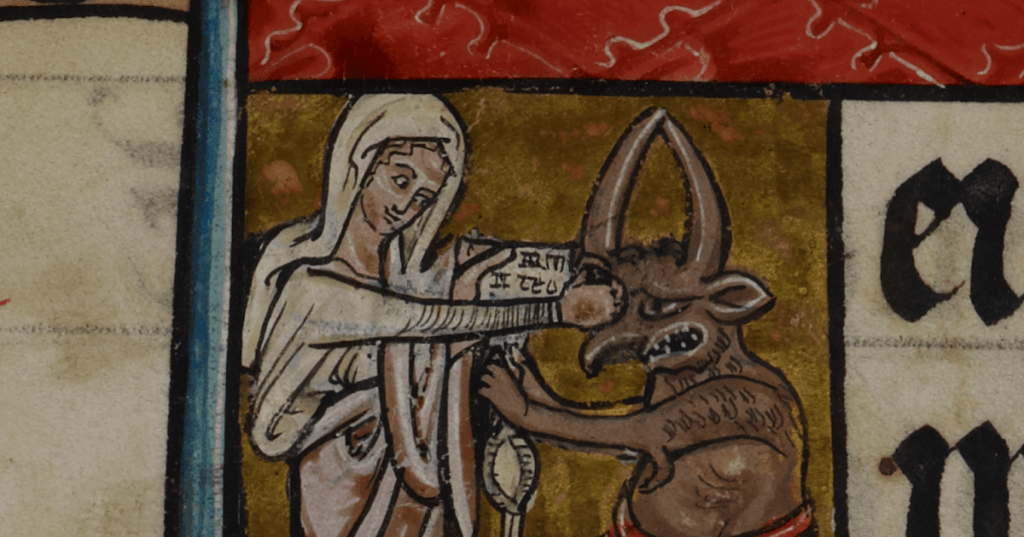

I agree that values present themselves in the world as real entities. I disagree that the origin of these values is a red herring–I think that it matters very much. But I agree again that the experience of such values matters much more than debating or discussing them. To understand the reality of symbols we have to enact them, to incarnate them, in our daily lives. The argument over when we started living in our modern linear, factual. and personalized way has a different contenders–some say the Reformation, the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, or the Industrial Revolution. Caroline Walker Bynum’s Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food for Medieval Women work hints that this process began in the late Middle Ages-early Renaissance, though answering this question was not the intent of her work.

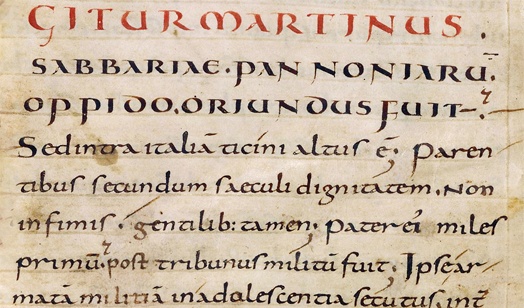

Bynum won me over immediately in her introduction. She makes it clear that we have to understand medievals on their own terms. She quotes John Tauler of the 14th century, who writes,

St. Bernard compared this Sacrament [the eucharist] with the human processes of eating when he used the similes of chewing, swallowing, assimilation, and digestion. To some this will seem crude, but let such refined persons be aware of pride, which comes from the devil; a humble spirit will not take offense at simple things.

The words form an introduction to the subject of her book, and indeed–unlike Henry Charles Lea–Bynum knows that to understand medieval ideas of food (or almost anything) means understanding the eucharist first and foremost. The words also bracket ones whole approach to any part of the past–humility usually triumphs over judgment.*

The humble everyday nature of food is a great place to start understanding the nature of things.

The remarkable Alexander Schemmen began his classic For the Life of the World with these words:

“Man is what he eats.” With this statement the German materialistic philosopher Feurbach thought he had put to an end all “idealistic” speculations about human nature. In fact, he was expressing, without knowing it, the most religious idea of man. For long before the same definition of man was given in Genesis. The biblical story of creation man is presented, first of all, as a hungry being, and the whole world as his food. . . . Man must eat in order to live; he must take into the world his body and transform into himself. He is indeed that which he eats, and the whole world is presented as one banquet table for man. It is the image of life at its creation and at its fulfillment at the end of time . . . “that you eat and drink at my table in my Kingdom” (Lk. 22:30).

We remember too, that just as, “the whole world is one banquet table” so too, the first sin involved breaking the fast. How and when we eat matters as to how we understand the world.**

Individually, food involves taking the life of something else and making it part of ones own life. Even a stalk of wheat or an apple must be plucked from its source of life and ‘die’ so that we may live. So eating mirrors Christ’s life, death, and resurrection. I talked in a recent post about adopting a theopomorphic view of our experience with the concept of bodies, and we should understanding eating as part of our joining our life to Christ’s life. He offered himself as food for us (John 6:56).

In addition, eating joins us to creation’s pattern. The earth receives water and bears fruit. The earth receives death and decay–think compost or manure–and turns it into life. The church in the early west established “ember” days of fasting to mirror changes in seasons, and the longest fasts of the church year (Advent and Lent) occur during times of year when the ground lies essentially inactive.

Establishing this pattern, Bynum then leads into understanding medieval women and their relationship to food. Creation has always been associated with the feminine, i.e., “Mother Earth.” We know too the trope of the mother who “sacrifices herself,” who will eat less, eat last, or . . . not eat at all. She “dies” so that she can provide.

Bynum frames the context of medieval female religious experience through this lens. Bynum looks at the fasting and eucharistic devotion of certain medieval women, including a long discourse on the whether or not such women suffered from anorexia that is tedious in a scholarly way, but fair and sympathetic nonetheless.

But this intense personal piety as it related to food has a problematic endgame. Connecting fasting and feasting to the patterns in creation meant that communities could experience it together in the same way, with the same meaning. The physicality of things makes itself obvious to all, from the saint, to the scholar, to the ploughman. By separating the practice from “normal” rhythms, the experience became intensely personal, and less communal. This is not to say absolutely that no variance can exist in a community, and the late medievals never normalized the experience of these unusual women. But a decisive shift happened. Fasting meant no longer primarily a communal experience linked with the pattern of the life of Christ and creation, but a vehicle for personal, and possibly idiosyncratic, devotion.

From here dominos start to fall. Without the connection to creation, the common language of food might disappear. In time, one could fast from Netflix or shopping instead of certain foods. Maybe such things have their place for individuals, but the reduction of fasting to individual experience and individual authority robs us of meaning and identity (something Mary Douglas pointed out in her excellent work).

This same radical personalization and consequent loss of meaning have done similar work in the realm of sexuality. In ye olden days marriages happened not primarily because people were “in love,” but rather as a vehicle whereby people could participate in what it means to be human and the drama of salvation. If we think of our humanity and the humanity of Christ as one–before the foundation of the world–we see this clearly especially as it relates to women who get married:

- The woman is led to the altar by her father

- She “dies” at the altar–Miss Jane Smith is no more

- She is “reborn”–meet Mrs. Jane Johnson

- After marriage comes the “fruit” of the marriage, say hello to little baby Jack Johnson

The meaning of sexuality comes from this mirroring of Christ’s life, death, resurrection and ascension. And here we see why we need “Heaven,” and “Earth,” man, and woman, for our sexuality to make any sense at all. We have divorced this aspect of our being from all such patterns, and made it purely personal inside the chaotic variability of our minds. It appears the end of this rope has come, when some experts tell us that not only is the created order not a model for sexuality, but our very bodies should be discarded to achieve our purely personal goals.

Many today focus on our political confusion, and we should lament this. But these political issues have far deeper roots which we cannot see. Not only do we not see a pattern, we don’t expect to see a pattern. We won’t be able to solve these problems until we start looking.

Dave

*Another aspect of her writing that I appreciated . . . She delineated in the introduction chapters geared more towards layman like myself, and those written more with the professional scholar in mind. I personally have no taste for the hemming and hawing of scholar-speak, but I understand it has its place. It was kind of her to let me know what to avoid and where to focus my attention.

**This may seem a crazy assertion, but if we think of our lived experience we begin to understand. Let’s take drinking alcohol as an example. We instinctively recognize that someone who drinks scotch at 10 am has a problem, but if they did so at 10 pm, no problem. But why? What is the difference between drinking in the morning or at night?

Life is full of “inhaling” and “exhaling.” At night we begin to “exhale,” we reach the “fringe” of our being for the day. As we move through the “fringe” of the day we begin to approach the “chaos” of the unconscious. It intuitively makes sense, then, for us to match drinking something that relaxes us, that moves us toward the “fringe” of our being, at night rather than during the day. If we move towards the “fringe” in the morning when we should be “inhaling”–focusing and getting active–we create personal and societal dissonance. Our distinctions are not arbitrary.

Likewise, we understand that drinking socially is better than drinking alone. A person who drinks too much socially we might perceive as having a minor problem. A person who drinks too much alone we perceive as being in grave danger. But why? The pattern tells us, and again, we understand not so much logically but in our lived experience. Social groups exist for people to blend and mix together. Alcohol can bring us to the fringe of our being, we can “extend” the self in some respects through alcohol. Hence, “Can I buy you a drink?” can be a means of introduction in ways that, “Can I buy you some carrots?” would not. Someone who drank too much alone would extend themselves and connect with no one–it would be an intentionally fruitless action, in which we rightly recognize despair and nihilism.