Historians tend towards the romantic, which means they can develop an undue fascination with decay. The best historians add to this a grand sweeping view of all things and thus see (with good reason) the vicissitudes of time and the sin to which all men are drawn. Historians hopefully are not cranks or kill-joys–rather they at least believe themselves saying, “I’ve seen this movie before . . . . ”

Exceptions exist of course, but Polybius, while writing of the glorious successes of the Republic saw the wheel of time moving that same Republic inexorably towards decline. Oswald Spengler also shared the basic assumption that civilizations, like every living thing, had its inevitable death built into their DNA. Plato too saw forms of government moving in a definite cycle, and Machiavelli–though departing from Plato as much as he could philosophically–shared this basic assumption. He hoped that practical wisdom could elongate the good parts of the cycle and shorten the bad ones, but sought nothing beyond that. Toynbee, being more influenced by Christianity than any of the aforementioned greats, saw more hope but still admitted that every civilization he studied had declined and disappeared.

All of these historians (others could be mentioned, such as Thucydides, and though Herodotus may have been the most hopeful, he did not write about the Peloponnesian War) dealt with civilizational decline but not with the concept of time itself. Some might say that historians should not bother about “Time” and let it stand as the purview of either science or theology. Well, history involves a degree of science, and no one can write about mankind without at least subconsciously thinking about God.

Enter Olivier Clement, and his dense, difficult, but still fascinating Transfiguring Time: Understanding Time in Light of the Orthodox Tradition. I cannot claim to have understood him thoroughly, but I hope to have gleaned the most important aspects of his work.

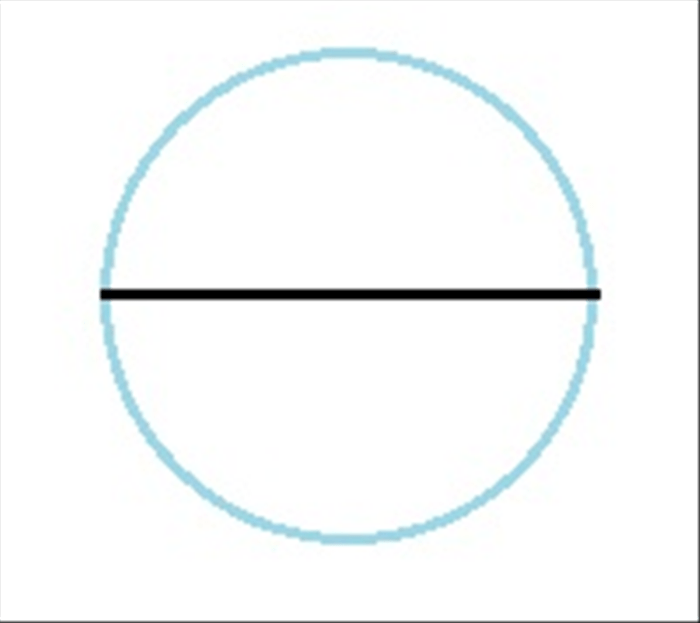

History shows us that civilizations had two main ways of conceiving of time, either as cyclical or linear. The cyclical view dominated most pre-Christian civilizations. Clement writes that

For primitive society, authentic time is the dawning moment of creation. At that moment . . . heaven was still very close to earth. . . . This first blessedness disappeared as a result of a fall, a cataclysm that separated heaven and earth . . . Thereafter he was isolated from the divine and from the cosmos.

The whole effort of fallen man was therefore to seek an end of this fallen state in order once again to be in paradise.

One sees this in the mythologies of most civilizations I am aware of. For the Greeks, Egyptians, Meso-Americans, etc. history begins with the gods ruling on earth in some capacity, a golden age of harmony and justice.

As the gods fled, all people had left to them was mimicry. By participating in the “cycles” initiated by the gods they could perhaps glean something. So we marry because heaven and earth were once married. We farm because of the motif of life from death, death from life we see played out in agriculture. Night becomes day, and day becomes night. Clement writes,

One important symbol (and ritual), the dance, sums up this conception of time. According to a very ancient tantric expression, the cosmos is the “game of god,” the divine dance. Primitive cyclical time is nothing less than the rhythm of this dance, ever tighter cycle in which the dancer is drawn in and assimilated.

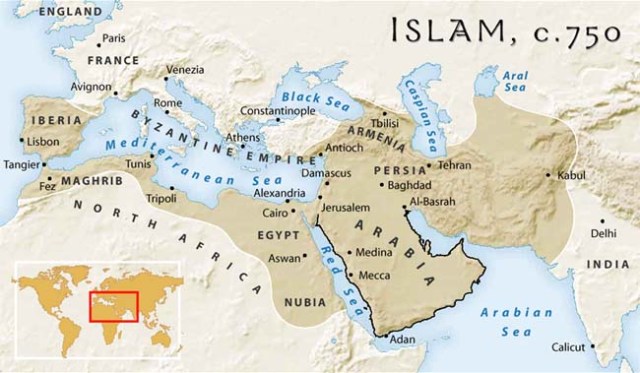

Clement acknowledges that much truth exists in this conception of time, but emphasizes that it is fruitless in the end and thus, hopeless, a “hellish” repetition.* “Time is always experienced as degradation” as we move further out from the original marriage of heaven and earth. As we move further out, our connection lessens, hence the origin of ecstatic religious manifestations as an attempt to escape the cycle of reality and return to innocence. The Dionysian cult, for example, was universally acknowledged as “new” by the Greeks in the 5th century. Toynbee mentions that in the aftermath of Hannibal’s invasion, the more disciplined Romans found themselves “plagued” with an onslaught of much more emotional religious expressions. The old gods could no longer meet the new needs

This severing of man from meaning makes time itself meaningless. Eventually not even the regularity of the cycles can entice. One sees this clearly in the Viking epic Egil’s Saga. The prose sparkles, and the poetry is even better. But in the end we have feast, feud, violence, victory–rinse and repeat. So too in other cultures. Clement cites the famous story of Narada from the Sayings of Sri Ramikrishna which illustrate this well:

Narada, the model of piety, gained the favor of Vishnu by his fervent devotion and asceticism. Narada demanded of Vishnu that he reveal to him the secret of his “maya.” Vishnu replied with an ambiguous smile, “Will you go over yonder to fetch me a little water?” “Certainly, master,” he replied, and began to walk to a distant village. Vishnu waited in the cool shade of a rock for him to return.

Narada knocked at the first door he came to, eager to complete the errand. A very beautiful young woman opened the door and the saintly man experienced something entirely new in his life. He was spellbound by her eyes, which resembled those of Vishnu. He stood transfixed, forgetting why he had come. The young woman welcomed him in a friendly and straightforward way. Her voice was like that of a gold cord passed around the neck of a stranger.

He entered the house as if in a dream. The occupants of the house greeted him respectfully. He was greeted with honor, treated as a long lost friend. After some time he asked the father of the house for permission to marry his daughter who greeted him at the door. This is what everyone had been waiting for. He became a member of the household, sharing its burdens and joys.

Twelve years passed. He had three children and when his father-in-law died he became head of the family. In the 12th year the rainy season was especially violent. The rivers swelled and floods came down from the mountains and the village was swamped with water. During the night the waters swept away houses and cattle. Everyone fled.

Holding his wife with one hand and two of his children with the other, with the third perched on his shoulders, Narada left with great haste. He staggered along, battered by torrents of water. Suddenly he stumbled, and the child on his shoulders fell and plunged into the flood. With a cry of despair Narada let go of his two other children and flailed away to try and reach the littlest one, but he was too late. At this moment, the raging water swept away his wife and two other children.

He lost his own footing, and the flood took him away, dashing his head against a rock. He lost consciousness. We he awoke he could see only a vast plain of muddy water, and he wept for his loss. He heard a familiar voice, “My child, where is the water you said you would fetch me. I have been waiting for almost ½ an hour.”

Narada turned and saw only desert scorched by the mid-day sun. Vishnu sat beside him and smiled with cruel tenderness, “Do you now understand the secret of my maya?”

Commenting on this story, Clement cites two Hindu scholars, who write that,

The nature of each existing thing is its own instantaneity, created from an incalculable number of destructions of stasis.

and

Because the transformation from existence non-existence is instantaneous, there is no movement.

Thus, for Hindus as well as Greeks, eternity is seen in opposition to time, with immobility being the means of entering into eternity, which is again, in opposition to all that is transitory on earth.**

Viewed against other pre-Christian societies, Israel of the Old Testament looks quite different in their view of time and space. Some comment on the “crudeness” of the anthropomorphic language in the Old Testament about God, but this language, “demonstrates that eternity is oriented towards time, and that eternity marches with time towards encounter and fulfillment.” Clement uses the word “courtship” to describe this relationship, which I find most apt. One might then say that the Old Testament culminates in the Virgin Mary bearing the union of Heaven and Earth in the person of Christ. Time takes on a linear dimension and events take on definite meaning. True–time is part of creation and thus partakes of the curse of the fall–it marches us towards death and non-being. Existence gets mechanized. But this also means time will be redeemed, and this process of redemption begins not at the future “Day of the Lord,” but in the Incarnation itself, and in the everyday “now.”

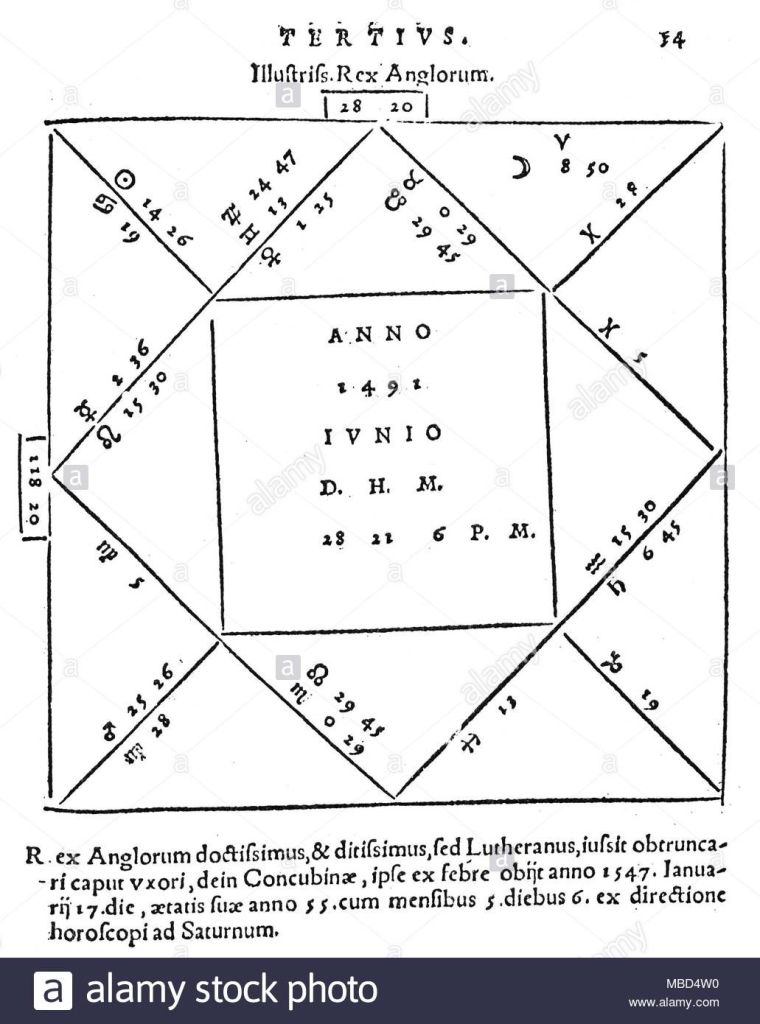

The Christian worldview has elements of the cyclical time of many pre-Christian civilizations. Many medieval calendars, for example were often expressed in a circular, not linear, manner.

The Church is both eschatological and paradisal–a paradise regained–though importantly, a paradise regained that will be greater than that which was lost. Levitical liturgical life prescribed yearly festivals that mirrored the seasons of the year. In some ways, the world is a “game of God,” as St. Maximos the Confessor states.^ The liturgy recapitulates not our vain longings for a return as in pagan cultures, but the real interaction of time and eternity at the heart of existence.

In the Old Testament, time had meaning in part because it moved to a definite fulfillment with the coming of the Messiah. With the Messiah rejected, the Jewish people lost their connection with the eternal purpose of time. Now time as a straight line simply ends in death, and proclaims the reign of death just as strongly as the vain repetitive cycles of the most ancient cultures.

If I understood Clement rightly, he argues that the Christian sense of time preserves the best of both Jewish and pagan time–the cyclical and the linear–while introducing an entirely new element. The liturgical cycles give us continual entrance into a defined pattern life as we move in a distinctly forward direction towards the Day of the Lord. But these cycles don’t just recall the past or proclaim the future, but bring about an intersection of eternal and temporal. Liturgical prayers often speak of the “today” of the historical event celebrated. And if time is part of creation, then the “line” of history too will be redeemed and circumscribed by eternity.

As to the implications on blog about history and culture, well, here I have less confidence than in my attempts to understand Clement. But if I may venture forth . . . it does seem that an undue amount of political commentators have fallen prey to the romantic idea of cyclical and irretrievable decay. Right after Trump was elected, for example, a new edition of Plutarch’s lives detailing the end of the Roman Republic got published. Some now on the right feel a leftist totalitarianism on the rise. But Clement would tell us that is at precisely these times that we must remember: time no longer bears us unceasingly towards decay. If we so choose, we can live in a world infused with the paradise of eternity.

Dave

*Clement mentions that many ancient societies buried their dead in the fetal position as an indication that the cycle of life/death was to repeat ad infinitum. Many Native American tribes did this, as did the Egyptians, apparently. As far as I know, Christians have never buried their dead in a like position, testifying to a different theology of time and redemption.

Cremation practiced at times by the Greeks and others also testifies in some ways to the futility of the cycle–we began as nothing and return to nothing.

**Clement notes some similarity between this concept of “immobility” and Orthodox ascesis. Many monastic fathers speak of “stillness of heart” and “remaining in your cell.” Again, Clement acknowledges the complexity of the topic and the need to emphasize that sometimes the differences are not of “kind” but of degree & orientation.

^The idea being not something arbitrary but something playful and in flux, compared to the stability of the heavenly realms.