There is a section of Plato’s Laws in which the “wise” Athenian states that,

Countless ages before the foundation of modern states, they say there existed a form of government in the age of Cronus that was a great success. The traditional account tells of the happy life led then, and how they had everything in abundance without toil.

The reason alleged for it is this: Cronus knew that human nature is never able to take complete control of human affairs without falling to arrogance and injustice. Bearing this in mind, he appointed kings; but they were not men, but beings of a higher order, that is, spirits. We act on the same principle today in regards to our domesticated animals. We don’t put goats in charge of goats, or cattle in charge of cattle, but control them ourselves.

The story has a moral for us, for when men rule a state we have no respite from toil. We should make every effort to imitate life under Cronus; we should run our private and public lives in obedience to whatever divine spark remains in us, and dignify this distribution of reason with the name ‘law.’

But today . . . most take the line that laws should be given not to the end of attaining virtue or even waging war, but to safeguard the interests of the established political system, whatever it is, so that it is never overthrown and remains always in force. The point is this–whoever is in control lays down the law, right?

For many of us this may seem remarkably modern, and perhaps even a cynical, viewpoint on politics as nothing but the manipulation of power to serve the interests of power. But from his other writings, and indeed, the whole of The Laws we know that Plato may have not thought much of the politics of his day, but certainly believed in the possibility of a better world through the application of the right political practices. His reference to the time of Cronus likely hearkens to his belief that this wisdom had to come from outside or above the world of experience.

Plato seems to be saying that when one abandons a transcendent ideal, the power of men over other men can only get reduced to pure power. If I am right about that, perhaps Plato is wrong. I’m not sure that any concept of power can come without a “spiritual” reason, plainly spoken or otherwise.

K.R. Bradley’s Slaves and Masters in the Roman Empire: A Study in Social Control bears all of the marks of the professional classicist–long on important and impressive detail (he cites some primary sources I have never heard of before), a bit short on style. Yet a philosophy emerges behind Bradley’s many details, one that Plato might understand: When men must rule other men who have no wish to be ruled, one must use a complex system of rewards and punishments, all towards the goal of maintaining control–of maintaining power. Bradley’s concern lies there, and only there, and therein lies my objection.

Writing about slavery brings with it certain necessary introductory statements:

- Just because slavery was a common social institution in the ancient world does not mean that it is ok. Indeed, the existence of slavery anywhere at anytime is tragic.

- Although slavery is bad, it might be that certain forms of slavery at certain times and places was better than other forms. Calling one form of slavery better than another would not mean that the better form was “good,” in itself, but only less bad.

First let us consider the concept of power and control. On the one hand we have the theocratic forms, where God, a god, gods, or their representative(s) make judgments in their name. These forms very obviously appeal to something outside the system to run the system. To that extent at least, Plato would approve. But what of systems that have no defined referent? Well, just because we cannot definitively name the outside referent/intelligence doesn’t mean it isn’t there.

We can use the example of school. Of course students are not slaves, but very few of them over 12 want to be there, and they outnumber all those in authority by a large margin. Teachers obviously benefit from centuries of social expectations, but to control a class, they need to liturgically fulfill certain expectations of what a teacher is and does. If you go too far outside the lines, you break the spell, and your authority disappears, something Key and Peele know well (see clip here–for some reason it would not imbed in the post).

The materialist might argue that obviously the teacher in question could restore order in the class. Of course, the clip above is not real life. But those who have taught know that reestablishing control in such a situation would involve a great deal of work and some deft maneuvering. That control could possibly come from force, i.e., “Everyone be quiet or get sent to the office,” accompanied with stomping and yelling. But that kind of power has a very short shelf life. Threat and fear cannot provide a foundation for learning–it is a strictly materialist structure. Students know this, and will always defeat a teacher who uses force too often, akin to Paul Kennedy’s “imperial overstretch.”

If we reflect on our experience, a teacher has authority when they put on the “body” of a teacher. This means

- Knowing your subject

- Being on time for class

- Having everything ready for class

And so on. One must continually inhabit this “body” every time you enter a classroom. I have taught for 24 years, but if I set up the projector to play a video, quiet everyone down, press “play,” and technology fails me, I have about 7 seconds to get it to work. Otherwise, the “teacher” flees and the spell breaks. Order resets only as I re-inhabit the teacher body.*

Certain aspects of Roman slavery in the Imperial age may surprise us:

- Slaves were encouraged to marry and have children, and exemption from work came especially to women with at least 3 children.

- Emancipation from slavery may not have been common per se, but was a regular feature built into the institution.

- Cato (I had heard of before) and Columella (not heard of him before) both testify that slaves had certain holidays designated just for them, and along with designated times of rest, had perhaps about 75 days off during the year (this would apply at least to rural slaves, who probably had worse treatment than household slaves).

- During these slave holidays, they had relative freedom of movement

- Romans wrote admiringly of slaves who stood by their masters, and saw them capable of living out the Roman virtues of pietas and fidelity.

The fact that republican Rome had three major slave rebellions between 140-70 B.C., and none to speak of in the imperial era could well mean that Rome found a better “pattern” of slavery, with “better” obviously not meaning “good.” Bradley takes this to mean only that Rome found a better systems of rewards and punishments, a better means of psychological manipulation. Perhaps . . . but it seems to me that Bradley has a very one-dimensional view of power. He forgets the collective intelligence inherent in any group. Again, slavery is bad, but even an oppressive system cannot work solely based on a materialistic appeal to fear, or even a proper balancing of reward and punishment. Something must guide it.

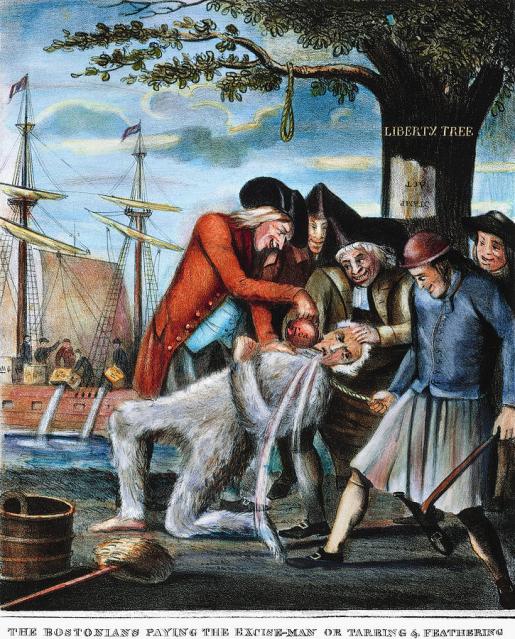

Bertrand de Jouvenel’s On Power: It’s History and Growth, at certain moments at least, brilliantly shows what happens to governmental authority over time, increasing even though nobody necessarily intends such growth. Every revolution in the modern era shows this pattern. Lenin was much worse than any czar, Mao much worse than Chang Kai Shek, Robespierre outdid by great enormities anything Louis XVI envisioned, and so on. Even the American Revolution followed this pattern. George III may lacked a certain mental alacrity, but he never seized property and exiled any of his political foes among the colonists. The newly minted United States performed this task instead with those who remained loyal to the British. And speaking of slavery, slavery increased dramatically after the Revolution, despite the, I believe, genuine expectation that it would disappear within a generation. A variety of economic and sociological reasons exist for why they were wrong, but “the rest of the story” must exist somewhere. Democracy, conceived as a rebellion against tyranny, may be most prone to this logic precisely because “the people” cannot repent as an individual might.

The latter sections of this book (which I have not yet read, but skimmed portions) promise much in the way of historical examples. In the early sections Jouvenel explores various theories of the origins of power itself. Here he stumbles a bit, for he cannot quite figure out where power comes from. He begins with nominalist conceptions of power, which means that abstract concepts have no validity, but we assign names for convenience. He admires Rome’s Republic, stating

[The Romans] of “the Senate and people of Rome.” [They] had little need of the word “state” because they were not conscious of a thing transcendent, living above and beyond themselves . . . . In this conception, the reality that Rome bequeathed to the Middle Ages, the only reality is men.

Jouvenel says rightly that Romans never thought of a “state,” but they did think of a Senate that functioned as a body, and they had the “people” also represented as a body. Individual men cannot be the only reality. Senators made up The Senate. He quotes Aquinas approvingly when he wrote,

Any group would break up if there were none to take care of it. And in the same way the body of a man, like that of any other animal, would fall to pieces if there were not a directing force within it seeking the common good of all members. . . . In every mass of men there must be the same principle of direction.

Jouvenel examines some other philosophical ideas about power and can only conclude that,

Power possesses some mysterious force of attraction by which it can quickly bring to heal even intellectual systems conceived to hurt it. There we see one of Power’s attributes. Something it is which endures, something which can produce both physical and moral effects. Can we yet say that understand its nature? We cannot. Away then with these fine theories which have taught us nothing . . .

These “fine theories” essentially belong to the field of “emergence” or bottom-up ideas about the establishment of power. Our experience shows us that some kind of intelligence, some kind of reality, hovers above or around certain activities. For example, in an Orthodox worship service there are a variety of prayers or confessions repeated every week that I have memorized over the years. But . . . this memorization of mine applies to the church service only. If you stopped me on the street randomly and asked me to repeat the confession before communion, I wouldn’t get it right. The materialist would ascribe this likely to mere mental association, and while that no doubt plays a part, I’m convinced

From here he explores what he calls “Magical” theories of power, some of which still exist in traditional societies. Most interesting to me from this group is Joseph Frazer’s “Sacrificial King.” This form requires some kind of descent from the king to renew the power of the office. This sacrifice can take various forms, and some would not look like sacrifices to us now, but this principle of descending to ascend, and having this process repeated, enacts a pattern where authority rarely gets abused. The taboos surrounding the office have a binding strength that prevents such abuse.

I am convinced that here we have the true origins of real power (though obviously some manifestations of this model cited by Jouvenel deviate sharply from Christian morality), for it models descent and ascent of Christ Himself.

To return to classroom experience, our best teachers likely instantiated a definite pattern into their classroom–that forms the “high” aspect of their authority. But they likely also “descend” and come alongside you to help you with class or possibly a personal issue. When they do this, they in effect climb into the body of “Teacher.” Those who own slaves can succeed in putting an imprint of themselves on the people they “own.” Bradley shares some stories of slaves who grew very attached to their “owners” and even suffered and died on their behalf. But such power does not deserve the name because it fails to free, and instead can only end in death. On the flip side, some today argue that suffering gives power, hence, the so-called “victim Olympics.” But Christ does not receive power from on high merely because of His suffering, but because He conquered death in His suffering. Today’s “sufferers” often wish to remain victims, thinking that only the descent gives one power. Not so–recall a teacher from your past who “descended” and got too familiar with their students. Without an aspect of an Imprint from above, the body of “teacher” leaves those who only descend post haste. Students walk all over such “teachers.”

Comparing citizens to students breaks down quickly–not nearly as quickly as the comparison of citizens to slaves. But we cannot escape the fact that some guiding collective imprint from above forms our interactions with each other in the state. Whether or not this collective intelligence be angel or demon will depend on how their pattern of being mimics both the suffering and glory of Christ.

Dave

*When this happens, I will sometimes fix the problem, and then leave the room for 10 seconds merely to give me an occasion to re-enter and reestablish the body of a teacher–just like the Spanish Inquisition.