This was originally written in 2018 . . . .

*****************************

It seems that we occupy a strange place in our national life. We have more political divisions even though we have much less actual discretionary spending in the federal budget than in the past. President’s Trump and Obama function/ed largely as symbols for their supporters and detractors. Many do not care much to look at their particular actions, rather, an action becomes bad or good because of who did it. We have a hard time seeing past the ad hominem.

But this should not surprise us. Perhaps it is our very lack of flexibility in the budget that heightens the symbolic role of the president. I suspect also that especially since the end of the Cold War, and probably since Vietnam, America has searched for a new identity, and forming an identity requires strong symbols. And, while I think that we would struggle in our political life currently in any case because of this, as (bad) luck would have it, our last two presidents have been near opposites in terms of their personalities and style. Some argue that Obama was the far more “rational” president, but even if that were true, Obama’s supporters had a strong emotional, gut-level attachment to him, akin to Trump’s current supporters. In any case, we will miss what is really happening if we focus only on the policies, or the outward appearance of things (though to be sure, we could use some dispassionate focus on what presidents are actually doing in addition to their symbolic perception).

What is a president, exactly?

Childish interpretations of kingship in earlier eras tend to argue along the lines of, “Kings dressed up in all their finery because they were greedy, cruel, and didn’t care about the people.” Much better interpretations see monarchs as an extension of the people themselves in some way. The people would not want them to dress in a dowdy fashion, for that would reflect poorly on them too. So, for example, many Frenchman took great pride in the fact that Louis XIV could eat 2-3x more than a normal man with no apparent ill effects. But I have struggled with even some of these more sympathetic approaches. I still feel that they leave something out.

Alice Hunt’s The Drama of Coronation brings out many nuances and subtleties of English coronation rites. She demonstrates a great ability to let the texts breathe and speak for themselves. Her analysis strikes me as fair and careful, and her comments attempt to illumine what for 21st-century moderns is a great mystery. She traces the coronations of five English monarchs in attempt to answer the question:

a great ability to let the texts breathe and speak for themselves. Her analysis strikes me as fair and careful, and her comments attempt to illumine what for 21st-century moderns is a great mystery. She traces the coronations of five English monarchs in attempt to answer the question:

What is a king (or queen), exactly?

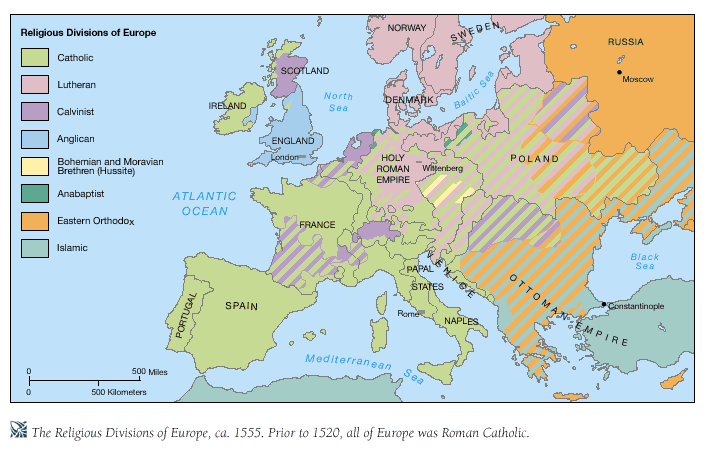

We will miss the mark widely if we think only in terms of having an executive function in government. One problem that faces historians with this question is that we have very few records of medieval coronation rites. This in itself gives us a clue that coronation ceremonies had a primarily religious function. In the older Byzantine rite, we see that the public, and even catechumens, had to leave the service during the canon of the mass. In the western rite of St. Gregory the Great, the confession of sin has communicants proclaim, “I will not speak of thy mysteries to thine enemies.” Hunt suggests that at least beginning with Pepin the Short, coronations took place in a sacramental and liturgical sphere, which would have meant “private” in at least some ways.

But we have many records or eyewitnesses of England’s 16th-century coronations. The crowning of Henry VIII would not have been unusual, but each subsequent coronation had its own unique elements that perhaps called for a more public justification, aside from the turbulent historical circumstances:

- Anne Boleyn was crowned. The fact that a new queen would be publicly crowned while the king still reigned was entirely novel.

- The coronations of Mary and Elizabeth as “queens regnant” had not happened before

- Edward VI coronation involved that of a boy king amidst stark religious changes

As mentioned, Hunt handles the sources marvelously. My only quibble is one that I have with many (it seems) English historians, which involves their failure to raise their eyes above the various perspectives and declare something definite. I am all for intellectual humility, but sometimes it takes more humility to take a risk of being wrong than to say nothing at all.

The first issue Hunt tackles involves historians who try and argue for something along the lines of “exploitation of ceremonies” to achieve power. She cites some historians of the Wars of the Roses that accuse the Yorkist faction of attempting just this to achieve power. Hunt dismisses this perspective quickly. Along with David Kertzer and others, she argues that ceremonies don’t exploit as much as they create legitimate rule. This may sound silly to some modern ears if they think only of ancient robes and mitres. But if we imagine a disputed presidential election in the U.S., and one candidate had the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court administer the oath of office, we would not say that he “exploited ceremony.” Rather, the ceremony–at least in part–made him president. He could not be president without the ceremony, nor would we say the ceremony meant nothing more than empty ritual.

Henry VIII gives us a good place to begin as the last great coronation before the Reformation. Here we reside in the realm, so we imagine, of absolute divine right before the advent of more popular Reformation polities. But just as the Roman emperors opposed themselves to the aristocratic senate and ruled in the name of the people, so too did Henry and other European kings. Kingship had an element of “popularity” about it, in the strict sense of the Latin meaning of “populares.” Hunt quotes from the Liber Regalis:

Here followers a device for the manner and order of Coronation of the most excellent and Christian prince Henry VIII, rightful and undoubted inheritor of the Crown of England and of France with all appurtenances, which is only by the whole assed and consent of every of the three estates of his realm.

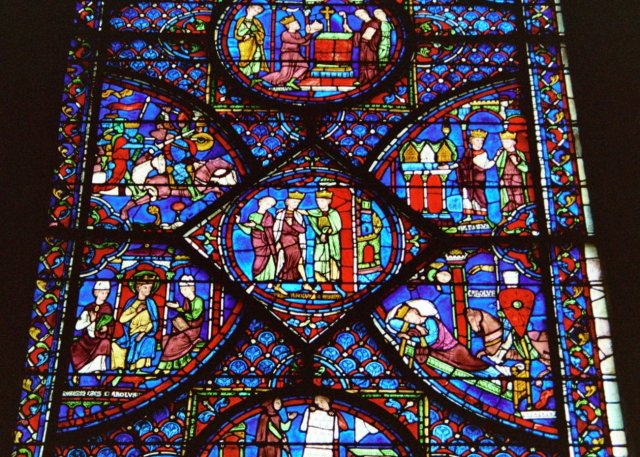

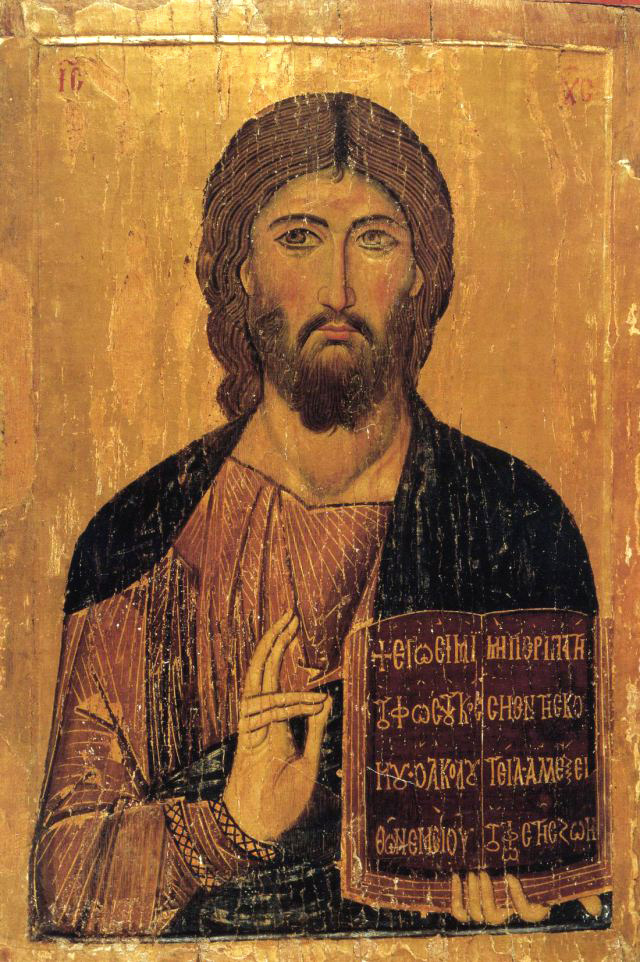

Henry’s legitimacy is real, rooted not just in Heaven but on Earth. Thus, the “physicality” of his rule has a reflection in his person, and required the physical objects of rulers past, especially the chalice of St. Edward, among other things. These various objects had a hierarchy of value, and who carried them and where people processed gave rather than reflected status. Contra the modern assumption of the homogenization of space and time, the king stood somewhere between heaven and earth. Heaven of course was not earth, but the two met in various times and places in the medieval view. Church buildings themselves were a touchstone, and the designs of the buildings manifested this.* Clergy were consecrated, set apart, so they could receive the ultimate intersection between heaven and earth–the holy eucharist. The City of God was not the City of Man, but they sought to model earthly order on heavenly order, or reality itself. Thus, officiating clergy elevated the king at a certain point in the coronation, just as they would elevate the bread and wine. The ceremony made the connection of “consecration” immediately obvious to all.

Many assume that Henry’s Reformation might make such “catholic” ceremonies obsolete, but in fact Henry seems to have gone “all out” in Anne’s coronation ceremony. To start, he held a separate coronation service for her, which may have had no precedent. Second, the ceremony took place on Whitsunday (Pentecost), the second most holy day in the church calendar. Third, Henry absented himself from being seen directly during the ceremony itself, which gave him more “god-like” status, the unseen yet present “earthly god” bidding Anne receive the crown. Finally, Henry wanted for Anne to wear Katherine’s crown during the ceremony. Yet here even Henry met a roadblock he could not overcome, as the man in charge of the crown would not give it up. The ambassador of Venice relates,

Accordingly, the king wrathfully sent to the one who has charge of the queen’s [i.e. Katherine] crown, Master Sadocho by name, a great man in that island, requiring the crown for the coronation. Master Sadocho replied he could not give it up because of the oath he had taken to the said queen, that he would guard that crown faithfully. The king then went to see him and expressed his desire. At this, Master Sadocho, who is a man of ripe age, took off his cap and flung it to the ground without saying a word. When the king saw this he asked what moved him to do such a thing as this, to which Master Sadocho replied that rather than give him the crown he would suffer his head to lie where his cap did. . . . As he is a great personage who also has a son also of great worth and numerous followers, the king took no further steps, but had another crown made for the coronation of the new queen, who has been pregnant for five months.

Obviously, symbols had real meaning for those outside of the king and clergy.

In all these things Henry to me seems to overreach, realizing the precarious nature of his enterprise. He had founded a new church, divorced/annulled his marriage with Katherine, and married someone already pregnant. He gave Anne all the symbolism he could. Prayers said during the coronation directly assumed that the child Anne carried was a boy. Alas for Anne, perhaps the connection between symbolism and reality could only go so far.

The real shift took place with Edward VI. Here we had a combination of 1) No Henry to go all out to get his way, 2) More evangelical reformers in charge in the Church of England, 3) A boy king who had no real say in what went on. The crucial distinction came when Bishop Cranmer stated that, “the oil [for consecration], if added, is but a ceremony,” and not strictly necessary. Nothing really happens at the coronation that could not happen elsewhere. Heredity, the system, and his oath made Edward king, and nothing more. Certainly the ceremony had to have the Church presiding–or so it seemed obvious at the time–but the Church no longer had to “do” anything important.

One might argue that this shifted politics wholly into the realm of the secular, and so made kingship defendant on the right exercise of power. This made kings potentially just as politically vulnerable as any president, but in a more precarious position, as Charles I and Louis XVI discovered.

As a culture, we clearly crave symbolic archetypes more than in the past. We see this in the consistent popularity of super-hero movies, and the somewhat polarizing popularity of Jordan Peterson. We see it in recent political commentary, as a handful of mostly normal people believed that Obama was the anti-Christ in 2008, or that Bush and Trump were/are Nazis. We see it in our woeful neglect of Congress–perhaps there are just too many of them to affix any meaningful archetypes. It may be that we are forced into this symbolic realm by the incomprehensibility of our laws. However we got here, this unsettling political moment gives our culture some interesting opportunities to understand our symbols and to recover an older view of reality.

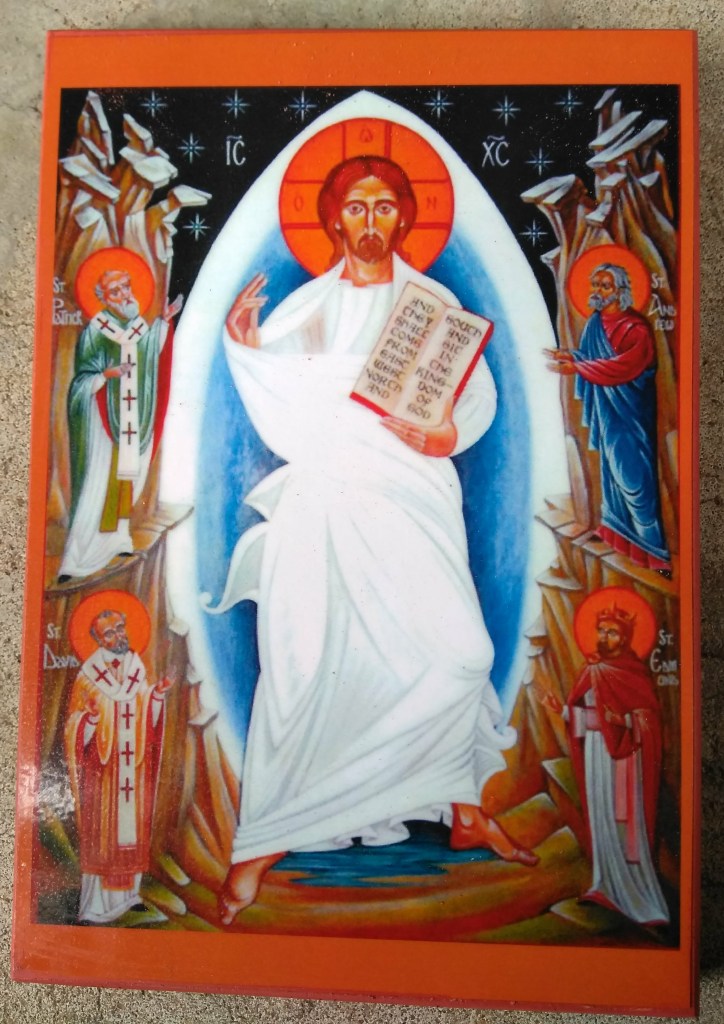

Today we tend to assume that if something is a symbol it is not really real, but only a signifier for the real. Hence, we know what a male sign for the bathroom means, even though of course no one in the bathroom looks like the symbol. Symbol and reality live in different worlds, in different planes of meaning. But the older meaning of “symbol” meant the bringing together of reality to create “real” meaning. St. Maximos the Confessor writes,

…for he who starting from the spiritual world sees appear the visible world or else who sees appear symbolically the contour of spiritual things freeing themselves from visible things… that one does not consider anything of what is visible as impure, because he does not find any irreconcilable contradiction with the ideas of things.

To quote Jonathan Pageau, “a symbol is a meeting place of two worlds, the meeting of the will of God with His creation.” Pageau goes on to say that the most real things are that way because precisely because they are symbols. Reality “really happens” when heaven and earth unite, when they “symbol together.”^

I can’t say for sure if this older view of reality will help us understand exactly what a president is, but I think it will help. The more self-aware we can be of what we are doing, the more hope we have. Then, maybe we can go back to the lemonade on the porch days of debating the finer points of Social Security reform.

Dave

*Pageau talks mostly of church designs in the eastern Roman empire, though his point applies in the west, though with different applications.

**I am indebted to Pageau’s article here: https://www.orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-recovery-of-symbolism/

^This is exactly what St. Luke tells us the Virgin Mary did in Lk. 2:19 when she “gathered” or (as the Greek states) “symballoussa” all of what had happened to her.