It is sometimes possible to enjoy a book that one cannot understand very much of, provided that

- The author has a great deal of fun with the subject, and

- The author clearly and deeply understands the subject, which allows him to express his ideas clearly.

I confess to knowing nothing about almost all of the authors CS Lewis discusses in his wonderful English Literature of the Sixteenth Century. Anecdotes exist that indicate Lewis felt real heaviness and irritation in cranking this one out, but this does not come across in the writing. It reads light as a feather. Lewis generously shares his opinions about literature, but mixes these opinions with a marbling of philosophy, history, and cultural analysis. All this makes Lewis’ work come alive and relevant for today. This is some of Lewis’ best writing, and his wit and humor shine on most every page.

Lewis finds this era worthy of extended examination because it stands at a nexus of a variety of momentous shifts:

- The early 16th century saw the last vestiges of the medieval worldview have their final say

- The early-mid 16th century saw the high water mark of Renaissance humanism and classicism

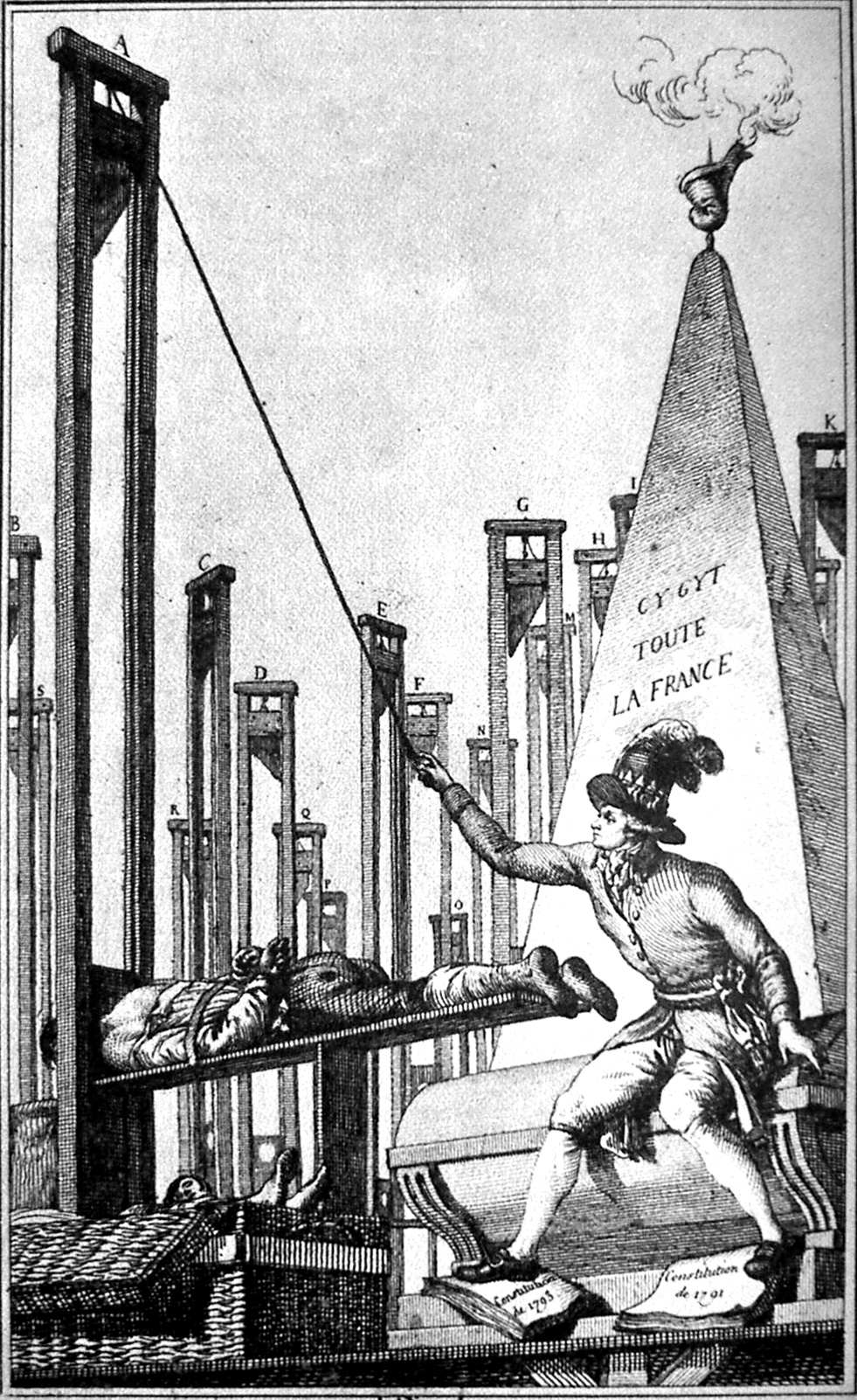

- The entire 16th century saw tumultuous religious upheaval caused by the Reformation, followed on by the Counter-Reformation.

Lewis keeps his focus on the literature, as is proper, but his opening chapters also set the stage historically and culturally. For the historian, Lewis goes to great lengths to reset the balance between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, but I have covered that topic elsewhere. His basic point for in these opening chapters involves prepping us for the fact that literature at a nexus of cultural death and rebirth tends not to be very good. Things eventually sorted themselves out with Sidney, Spenser, and Shakespeare, but the early to middle part of the century left much to be desired. The main fault of the writers of this time involved a hyper-exaggeration of a certain strengths of cultural movements, which robbed much of their writing of life and merit.

To be sure, the political, cultural and religious tumult eventually settled into a new equilibrium, and after that, writers could borrow from different literary genres much more freely and productively, but until that happened, very little of anything transcendent value got written.

This dynamic makes sense to us if we scale down this larger point to something more tangible to our own experience of, for example, adolescence. Our early teen years involve an ending of childhood and the beginning of something else, akin to a larger scale cultural breakdown and rebirth in our immediate personal experience.

I grew up playing drums and listening to a lot of my dad’s music. This was a pre-headphone era, so we all heard what he played on the living room stereo. I got a healthy dose of the Beatles, Otis Redding, Willie Nelson, and Beethoven, among others. I enjoyed almost all of it. But as a 16 year old drummer, I wanted something else (unfortunately it took a few more years before I appreciated Ringo and Al Jackson), and a way to distinguish myself. One day, my cousin’s friend played for me the opening 30 seconds of Rush’s “The Spirit of Radio,” and it was all over for me. I was enchanted. I had never heard progressive rock, so I dove in headfirst. I immediately went to Tower Records and bought Permanent Waves, Moving Pictures, and Hemispheres.* For the next year, I then decided that everything about my drumming, and many other things about my life besides, must conform to Neil Peart’s particular style.

This improved my drumming in certain small ways but ruined it in others. Things got misshapen. If one believes (as I did), that even when drumming for my high school jazz band I should act like Neil Peart, you sound like an idiot. It took hearing a recording of my playing at the county jazz festival, and the judges comments, to make me realize I needed to snap out of it. I spent the following summer listening Glenn Miller and Count Basie, and at least partially fixed things for my senior year.

This was a classic, “It’s not you, it’s me,” problem. Neil Peart has much to teach any drummer, but not if you become enslaved to his aura. In that state, one plays drums essentially to convince an audience, and you lose all sense of proportion.

Times of personal and cultural death and rebirth offer many opportunities. In separating certain aspects of life from a larger context, we can see them with more clarity, and this is exciting. I’d like to think that in college, I could throw in occasional progressive wrinkles without being bound by them. Unfortunately our internal instability in those moments of initial discovery make it very difficult for us to take fruitful advantage of whatever insights we gain. The same applies to a culture at large. In the midst of breakdown, when things come apart, we notice what we had never seen before. This is great as far it goes, but it has to kept in balance.

Lewis shows us how this dynamic plays out in the literature of the period.

Oftentimes, what seems like an era in the fullness of its strength actually ends up being something akin to “terminal lucidity,” a burst of energy many dying patients experience before passing. For example, the 1980’s seemed like the crest of a wave of American confidence. We had Reagan-era optimism. We won the Cold War. We grew economically. We wore bright colors and made our hair big. But look again, and we see that some of what we were about shows an uncomfortable exaggeration of a theme. We should never have attempted, for example, “Hands Across America.” Big hair is one thing, and glam-metal fashion ca. 1988 quite another.

This “hyper-extension” of cultural posturing naturally collapsed, leading to completely opposite atmosphere. Now we had grunge music with lyrics about how bad things were, loose clothes (anyone who tucked in their shirt at my high school in 1990 would have been hopelessly labeled as a nerd), and “heroin chic.”

In neither era do men or women look particularly normal, with both exaggerating certain ideas to a point of being ridiculous.**

I much prefer medieval literature to that of the Renaissance, but by the end of the Middle Ages, we saw the same kind of unfortunate exaggerations. Lewis suggests that Scotland’s king James IV perfectly encapsulates the problem with the period. “Peak” medieval chivalry ca. 1350 had much to commend it. It ennobled men, and greatly elevated the status of women.^ The courtly love tradition had its good parts, though the best literature of the period grappled with some of the contradictions and tensions involved in knightly service of ladies. The literary figure of Lancelot encapsulates this well.

James IV (b. 1473, d. 1513) had many good qualities. He was open hearted, high spirited, and generous in the best spirit of chivalry. He had courage, but a variety of contemporaries remarked that he had too much courage to be king. He needed more prudence and policy. Many of his contemporaries felt that James never should have fought the Battle of Flodden, where he met his death (in Henry IV, Pt. 1 Shakespeare may have had James IV as a model in mind for Hotspur). As to the service of ladies, James IV almost parodies the medieval complexity and tension by abandoning himself to countless prostitutes and fathering a variety of illegitimate children. His exaggerated chivalric ideals made chivalry itself look ridiculous.

So too, late medieval literature had little balance and often none of the sense of play of the best medieval prose from previous decades. Lewis cites the work of John Fisher, who drank heavily from the medieval moral sense, but alas, could not let an idea go once he fixed himself upon it. In his The Perfect Religion, he instructs a nun to be

- Grateful for being created to live in a Christian society. As Lewis states, this is well and proper. But Fisher continues, telling the nun to be

- Grateful for being created at all. This is still a good sentiment, but perhaps was already covered in the first injunction? Fisher doesn’t stop there, however, urging that she remain

- Grateful that she was created as a human being, and not a toad, and tops this off with the counsel that

- She be grateful that she was created instead of all the other people that might have been created instead of her.

Lewis rightly points out that by the third injunction, Fisher has descended into absurdity (“she” could never be a toad—not an option for a human being,) and by the fourth, a work intended to promote Catholic orthodoxy seems to promote a gnostic heresy of the pre-existence of souls and the separation of the body from personhood. Lewis writes, “Fisher’s sincerity is undoubted, but his intellect is not as hard at work as he supposes. We can’t hold Fisher accountable for not answering his questions, but he doesn’t seem to know that he is raising them.”

This lack of balance spilled over into the religiously polemical works of Fisher and Thomas More. Both wrote defenses of purgatory, and both in their zeal latched onto certain rogue strands of late-medieval asceticism. In Dante, the souls in Purgatory sing psalms joyfully, and their bodies suffer in service of redemption, and is in fact an integral part of their redemption. For Fisher and More, we have denigration of the body, so that the purgation is for the sake of purgation itself, and their vision of purgatory means a practically pointless circle of suffering.

We should expect this tendency to exaggeration during times of cultural fragmentation. What was once solid now moves apart. The bell curve of ABC, CBS, and NBC turns into a thousand scattered points, first with cable news, then with the internet. When this scattering happens, we naturally lose our bearings and find what we can to latch onto. What we latch onto, however, will be isolated from a larger context, and thus will lose its relationship to the broader whole.

I have mentioned two late-medieval/early modern Catholics, now for some early Reformation humanists (though it was certainly possible to be a Catholic humanist, i.e. Erasmus). John Colet wished to return to a more pure age, and thus urged a strict “anti-body,” morality upon his readers. He saw no real difference between marital union and fornication, and in fact wished that no one would get married. Marriage and the body proved to messy for his taste. He acknowledged that no marriage would mean the end of the human race on earth, but oh well, these things happen.

The humanists loved classical culture, either for its perceived purity, hardy innocence, or merely because the classical age was not feudal and medieval, the worst of all sins. This meant that he abandoned allegorical or symbolic interpretations of the Bible in search of a platonic “pure” meaning of the text. Others shared these views, but his thoughts on the subject of Latin take him into absurdity in a similar way to Fisher. On the one hand, as mentioned, he was a strict moralist with gnostic tendencies. This led to a distrust of much of pagan literature. On the other, he hated all things medieval, and that meant hating medieval church Latin, which had been “corrupted” from the past that was pure, not in morality, perhaps, but in its use of language. Lewis writes,

{For Colet] the spirit of the classical writers was to be avoided like the plague, and their form to be imposed as an indispensable law. When he founded St. Paul’s school, the boys were to be guarded from every word that did not occur in Vergil or Cicero, and equally, from every idea that did. No more deadly or irrational scheme could have been propounded. Deadly, because it cut the boys off from all the best literature in the Latin world, and irrational, because it put absurd value on certain arbitrary elements dissociated from the spirit which begot them, and for whose sake they existed. For Colet, this seemed a small price to pay for excluding all barbarism, all corruption, all “adulterated” Latin.

We noted above that when something reaches its end, it can mimic strength through one final, exaggerated effort. It might seem on the one hand that Latin had no greater champion than Colet, who sought to emphasize only the “best” Latin. But Lewis points out that all of the efforts of the Renaissance humanists to preserve the purity of latin in fact killed it. A variety of medieval people actually spoke latin (churchmen and merchants), or at least some version of latin. Only a very few scholars knew classical Latin, and fewer still spoke it, and then only in the academy. The attempt to save Latin destroyed it.

It is usually more fun to read a review where the critic pans rather than praises. I have focused on the first half of the book, where the literature, with a few exceptions, stunk. But we should remember that the century ended with some of England’s greatest writers, and with Shakespeare we have an “all-timer.” When we recall Shakespeare’s best work, we see how much more comfortable he was with tension and play than the previous generation. He incorporated medieval and modern elements without going out of his way to defend either. Stylistically, he stuck to certain meters and forms, but not all the time. He could happily dance between them. His characters are rich, both particular to his time and universal.

This can give us hope for our own future. We live in an era where many of the old categories of meaning and belonging have vanished. As a result we see the same kinds of intensification and exaggeration that beset the 16th century. But they learned, and so might we. The path forward comes from Thomas More’s most famous and least understood work, his Utopia. As mentioned previously, Lewis felt that much of More’s polemical work fell prey to the vices of the age. Those vices, he argues, cloud our perception of Utopia. Many moderns attempt to find a point to the work, obscured or otherwise, that will clue us in to More’s meaning in the text. Much of More’s other work had a definite argument. So too must Utopia, right? Was More secretly supporting communism, or was he a closet Protestant? Or perhaps he sought to make some other political point buried in code?

Lewis points out, however, that any attempt to pin the book down specifically one way or another will fail, because More writes in this text like a medieval. Given that medievalism was practically dead at this point, it is no wonder that even his contemporaries remained confused. But Lewis argues the book has no particular point. It’s meant as a romp of this and that, no more, no less. The medievals loved to bandy ideas about and put them in tension and opposition to one another. For them, this was fun–and that signifies of a more healthy age than either our own or the early 16th century. They were more interested in play, we in logical, deductive writing that makes a point and gets somewhere definite.

For us, as for the 16th century, the way out of our predicament involves not stronger arguments, but a greater sense of fun. More shows us that even politics, whatever our position may be, can bear the weight of humor in any age.

*I also bought what was at that time their most recent album, Hold Your Fire. Rush fans may relate to my utter shock, bewilderment, and even anger at going from “Red Barchetta” to “Time Stand Still” in the space of 30 seconds. To this day I still feel that Hold Your Fire is a ridiculous album. Not until Counterparts would I start to forgive them.

**At first glance no two things could seem further apart than the late 80’s and early 90’s aesthetic. But both participate in the same cultural breakdown, and are likely, therefore to share some crucial commonalities. A second glance shows that, surprise, surprise, they have androgyny in common. In glam metal, a lot of guys dressed similarly to women (tight pants, makeup, etc.) and in grunge, a lot women looked like men (short hair, lack of showering, no care for appearance, etc.) No doubt grunge devotees would have been horrified to learn that they shared a crucial similarity with hair metal, but there you go.

In one section of the book, Lewis shows that Thomas More (Catholic) and William Tyndale (Protestant), who wrote page after page attacking one another, actually had a lot in common. Both had similar economic ideas. And on Henry VIII annulment and remarriage to Anne Boleyn, the hot-button issue of the day, they were in lock-step agreement. Both seem to have missed this fact at the time.

^For an example of this, note the famous story from Froissart about how Edward III heeded his wife’s call for clemency for the population of Calais.