A few years ago I wrote another post under this same theme about restaurant regulation in the EU, based off a particular quote from Arnold Toynbee, which reads,

In a previous part of this study we have seen that in the process of growth the several growing civilizations become differentiated from one another. We shall now find that, conversely, the qualitative effect of the standardization process is decline.

This idea that “standardization is decline” is exactly the sort of pithy phrase that drew the ire of many of Toynbee’s critics. In his work Toynbee attempted to create universal general laws of history based on his premise of the uniformity of human nature. Toynbee’s writing could sometimes degenerate into ideas that seem so general as to be almost meaningless.* On the subject of standardization, we easily see that surely not every instance of standardization brings decline and limits freedom. Standard traffic laws, for example, make driving much easier and much safer. Toynbee’s critics have a point.

But some of Toynbee’s critics seem afraid to say anything without caveating it a million different ways, and this too is another form of saying nothing at all. Toynbee’s assertion about standardization is of course is not true in every respect, but is it generally true?

I like historians like Toynbee who try and say things, and no one I’ve come across tries to “say things” like Ivan Illich. Toynbee threw down a magnificent challenge to the prevailing view of history (in his day) that more machines, more territory, more democracy, more everything meant progress for civilization.

But he did not know Ivan Illich, who allows almost no assumption of the modern world to go  unexamined. Toynbee poked at some of our pretty important cows. Illich often aims for the most sacred. In Medical Nemesis he challenges the assumption that people today are healthier than they were in the pre-industrial era. In ABC, he (with co-author Barry Sanders) attacks the idea that universal literacy brings unquestioned benefits to civilization. In fact, he argues the quest for rote literacy will end with meaninglessness and possibly, tyranny.

unexamined. Toynbee poked at some of our pretty important cows. Illich often aims for the most sacred. In Medical Nemesis he challenges the assumption that people today are healthier than they were in the pre-industrial era. In ABC, he (with co-author Barry Sanders) attacks the idea that universal literacy brings unquestioned benefits to civilization. In fact, he argues the quest for rote literacy will end with meaninglessness and possibly, tyranny.

Illich begins the book by referencing a quote of the historian Herodotus, who wrote 1000 years after the death of Polycrates. He commented that the tyrant of Samos,

was the first to set out to control the sea, apart from Minos of Knossos and others who might have done so as well. Certainly Polycrates was the first of those whom we call the human race.

Illich comments that,

Herodotus did not deny the existence of Minos, but for him Minos was not a human being in the literal sense. . . . [Herodotus] believed in gods and myths, but excluded him from the domain of events that could be described historically. He did not see it as his job to decipher a core of objective historical fact. He cheerfully [placed] historical truth alongside different kinds of truth.

This may seem an odd place to begin a book about language.

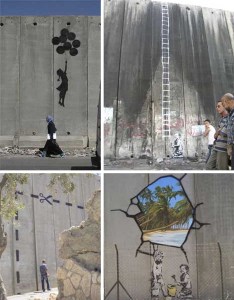

Later Greek and Roman historians attempted to explain the minotaur and Minos not as myth but as exaggerated historical reality. So, the sacrifice to the minotaur must really have been a sacrifice of perhaps money or troops to some cruel despot. Herodotus will have none of this, and neither will Illich. Those that seek to explain away myths attempt a kind of standardization of truth. This standardization inevitably involves a reduction, a narrowing, of the meaning of truth, language, and human experience. I think this explains why he begins with this quote from Herodotus.

Historians misread prehistory when they assume, Illich contends, that language is spoken in a wordless world. Of course words can exist without exactly defined meanings that last beyond the context in which they were spoken. But many often assume that this means we have barbarism because without an established language, we cannot have “education” in the sense that we mean it. Speech remains different from language. Lest we think that Illich is nuts, we should consider the impact of early forms of standardization:

- In ancient Egypt, scribes with a unified written language could keep records, and could thus hold people accountable to pay taxes, work on the pyramids, etc.

- In ancient China, too, the power of scribes over language gave them enormous power within the halls of power.

- Illich argues that medieval oaths used to be distinctly personal. Those that swore would clasp their shoulder, their hands, their thigh, and so on. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, with the rise of Roman, classical concepts of law came the fact that one’s signature stood as the seal of an oath. By “clear” we should think, opaque, or lacking substance because it lacks context. This impersonality can give way to tyranny.

- Henry II attempt at reforming English law (and thus, it would inevitably seem, unifying language as well) was done to increase his power by making it easier to govern and control the population. Does not much of modern law do the same thing?

- Isidore of Seville once wrote (ca. 1180) that letters “indicate figures speaking with sounds,” and admitted that until a herald spoke the words, they had no authority, because they had no meaning. The modern age allows those in power to multiply their authority merely through the distribution of lifeless pieces of paper.

- One of the first advocates for a universal language and literacy, Elio Nebrija, made his argument just after Columbus set sail. He bases his argument on hopes of creating a “unified and sovereign body of such shape and inner cohesion that centuries would not serve to undo it.” He frankly admits that the diversity of tongues presents a real problem for the crown.

Regarding Nebrija, Illich makes the thunderous point that he sought a universal language not to increase people’s reading but to limit it. “They waste their time on fancy novels and stories full of lies,” he writes to the king. A universal tongue promulgated from on high would put a stop to that.

We might be surprised to note that Queen Isabella (who does not always get good treatment in the history books) rejected Nebrija’s proposal, believing that, “every subject of her many kingdoms was so made by nature that he would reach dominion over his own tongue on his own.” Royal power, by the design of the cosmos, should not reach into local speech. Leave grammar to the scribes.

We live in a world of disembodied texts. The text can be analyzed, pored over, dissected in such a way as to kill it. As the texts lack a body, the text remains dead and inert.

But just as we assume that meaning comes when a text is analyzed rather than heard, so too we have created the idea of the self merely to analyze the self. Ancient people, up through the medieval period, do not possess a “self” in the modern sense. We see this in their literature. No stratified layers exist in an Odysseus, Aeneas, or Roland. No “self” exists apart from their actions. So too in the modern era the self lacks meaning unless the self is examined. So we turn ourselves inside out just as turn over the texts that transmit meaning. But who is more alive, Roland, Aeneas, and Alexander Nevsky, or the man on the psychologists couch?

We might think, maybe the drive for universal literacy back then meant squelching freedom but now surely it is a path to freedom. After all, we tout education as the pathway to independence, options in life, and so on. Illich will not let us off the hook. Education according to whom? Universal literacy, again, can only be achieved through universal language. And universal language implies a standardized education. So to prove we are educated we need the right piece of paper, paper only the government can grant.**

Back to square one again.

So the passion for universal literacy ends in the death of meaning, and the death of the self. In his final chapter Illich examines the newspeak of 1984 and sees it as the logical conclusion of universal literacy. Words will mean what the standard-bearers of words say they mean, and this in turn will define the nature of truth and experience itself.

ABC is a short book and easy to read. But in another way, reading Illich can be very demanding. He asks you not just to rethink everything, but to actually give up most everything you thought you knew. Agree or not, this makes him an important writer for our standardized and bureaucratic age.

Dave

*Obviously this post is not about Toynbee, but as much as I admire him and as much as I have learned from him, Toynbee’s latent and terribly damaging gnosticism (which comes from his failure to understand the Incarnation and the Resurrection) did at times lead him into a kind of a airy vagueness that greatly limits his persuasive power.

**I suppose to get Illich’s full argument on this score we would need to read his Deschooling Society.