Greetings Everyone,

This week we started our next book in our curriculum, Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Macbeth‘s plot is fairly straightforward, and this gives us a clear opportunity to see how Shakespeare’s literary genius shapes the meaning of the story through his use of language and setting. Shakespeare was also an expert psychologist, and again in this instance, the simple structure of the plot allows us to explore more fully what happens to a human being when they make the wrong choices.

Shakespeare inhabited a world where the concept of the “Great Chain of Being,” where each thing, and each being, in the created order has its proper place. When the world is properly ordered, the world becomes intelligible and we can know how to act meaningfully within the world. This concept stems from the Genesis creation account, which begins with chaos, and then over time God makes distinctions between sea and dry land, plants and animals, men and women, and so on.

Understanding this will help us put Macbeth’s terrible moral choices in the proper context, and the play explores, among other things, the questions of “what is a man?” and “what is a woman?”

We this theme introduced in Act I, Scene 1, where we meet the the “weird sisters,” the three witches. Their famously end this scene with the words,

Fair is foul, and foul is fair;

Hover through the fog and filthy air.

First, we note that Shakespeare wrote all of his plays in Iambic Pentameter. Iambic meters have a slightly lilting quality, with an alternation of unstressed and stressed syllables. The original tune for “Amazing Grace” is iambic, for example. But Shakespeare opens this play with the witches speaking in Trochaic Tetrameter. Trochaic meters have the opposite structure of iambs. Their first syllable is stressed, the second unstressed, and so on. Trochaic speech then, is often harsh and uneven, the opposite of melodic.

Here is a quick primer on Iambic Pentameter:

And here is a brief intro to trochaic tetrameter:

It makes sense that the witches would use this kind of speech, The rhythms contrast sharply to the speech of the other characters, which sets them apart phonetically but also spiritually. Fundamentally, the witches are not really women, and not really human. Of course, they possess the requisite DNA for a human being, but we would not want to define a human being strictly by DNA alone. Their evil actions deeply mar their humanity through by deeply eroding the image of God within them. More specifically, they are not just human beings generally but women in particular. For Shakespeare and others, women primarly have a nuturing role in the created order, and have the unique gift of bringing life into the world. Here in scene one, the witches (who have beards, another clue to the confusion of their being and their sex) talk of nothing other than murdering others through their manipulation of the elements.

Shakespeare has them meet on a heath, a particular kind of Scottish landscape. Heath’s are uncultivated, wild places, usually damp and misty, with scrub brush here and there. The disorder of the heath presage the disorder of the play. In such places, it is easy to get lost physically, and this mirrors the spiritual wilderness Macbeth will put himself in with his choices later in the play.

So while the plot of Macbeth is straightforward and satisfying in certain respects, the context in which the events unfold will challenge the views of modern readers. Many of us see our moral choices, whether good or bad, happening on something akin to a blank canvas. What matters for many today is not our surroundings or our bodies but merely our will. For Shakespeare and others of his time, an important ingredient in our moral choices was our place in the created order and those around us. In Shakespeare’s worldview, we invite ruin upon ourselves when we assume that our context, our place in the created order, can simply be overwritten by our mere choice. Such actions will inevitably confuse us and distort our view of reality, as happens to Macbeth. In addition, our confusion spreads to others and chaos reigns. Among many other truths, this play shows us that no man is an island.

Dave

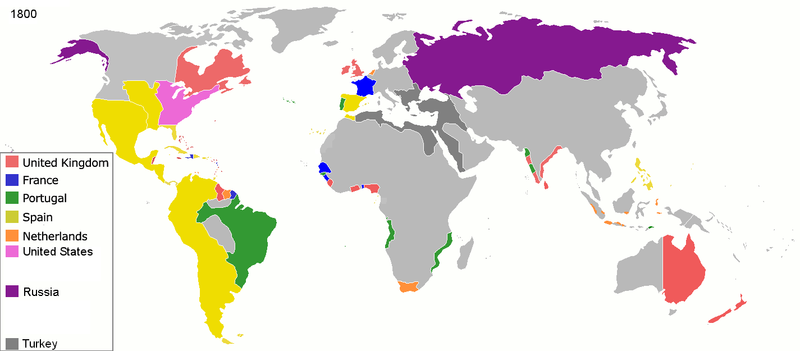

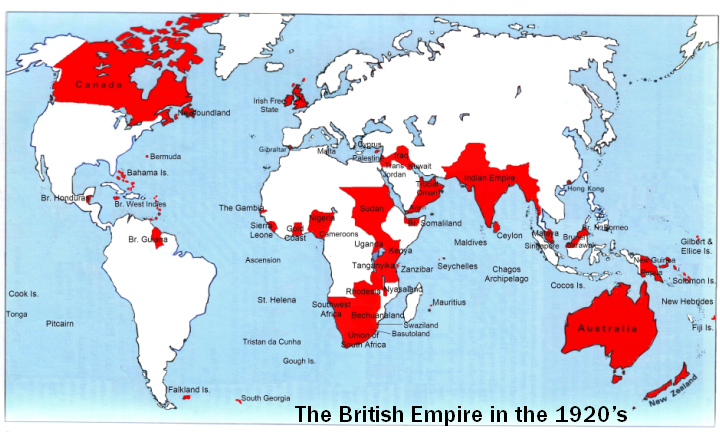

nd great wave of western exploration (the first being in the 15th-early 16th centuries via the Atlantic). Many hundreds of men risked everything for the sheer thrill of discovery, and yes, for the glory of it as well. In the early phases from ca. 1840-1860’s, most of this exploration seemed to me to have a generally innocent tinge to it. The more acquisitive imperialism came later.

nd great wave of western exploration (the first being in the 15th-early 16th centuries via the Atlantic). Many hundreds of men risked everything for the sheer thrill of discovery, and yes, for the glory of it as well. In the early phases from ca. 1840-1860’s, most of this exploration seemed to me to have a generally innocent tinge to it. The more acquisitive imperialism came later.